May 31, 2023

Download as PDF

View on The Brooklyn Rail

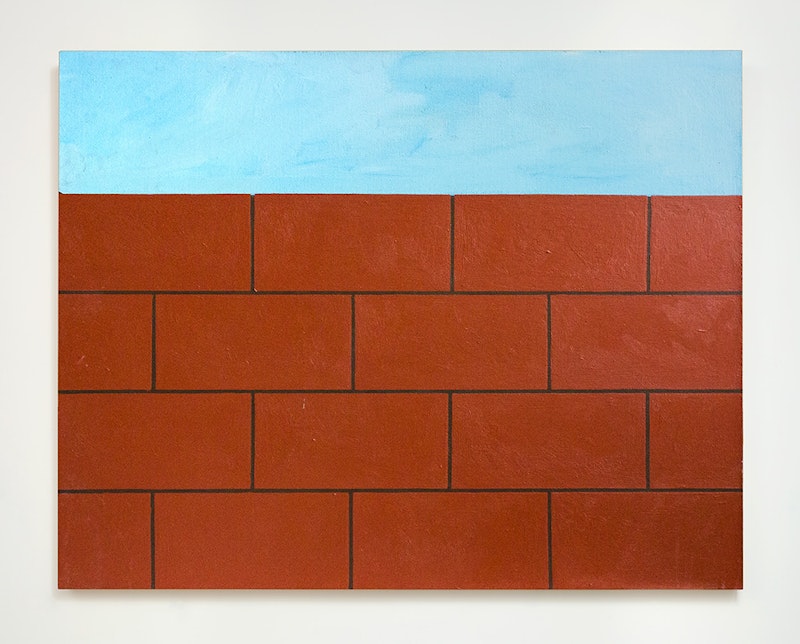

Peter Halley, Red Wall, 1980. Acrylic on canvas, 27 1⁄2 × 35 inches. Courtesy the artist, Craig Starr, and Karma.

The 1980s were formative years for Peter Halley, a New York artist best known for geometric paintings evoking prisons and cells, painted in florescent colors with industrial techniques. His dual shows currently on view at Karma and Craig Starr offer a privileged view into the artist’s earlier experimental work.

Choosing to split the exhibition into two parts allows each gallery to offer a distinct framing of Halley’s paintings. The space at Karma is open and bright, presenting bold works that seem continuous with the fabric of the city. The uptown show at Craig Starr, by contrast, feels walled off and cloistered. The gallery’s curtains are drawn, creating a soft barrier to the urban environment outside and allowing only a faint halo of natural illumination to mingle with the gallery’s overhead lights. These are the poles within which Halley’s work operates: one is either connected to the city or set against it.

For the most part, these exhibitions reveal a rougher side of Halley than we typically encounter in his work. In Red Wall (1980), exhibited at Craig Starr, a flat brick wall fills the picture plane. Each brick is painted thickly by hand, their flat uniformity unsettled against a clear blue sky. The wall feels impenetrable until the eye catches three indentations along the top row, where the black grout drops slightly below the brick. If the wall is an object that separates and dominates space, these gaps offer small avenues of escape, where the imagination can linger. In Monet’s Dream (1980), also at Craig Starr, a painting with a similar composition, Halley chooses to cap the brick wall with a long horizontal bar, closing its gaps and creating a disturbing sense of finitude.

At Karma we encounter The Prison of History (1981), a large painting of a gray wall with a barred window set against a black sky. Underlying the prison wall is a subtle red tone, with the wall’s grout taking on a pink hue. The underlying color foreshadows Halley’s interest in hidden structures—specifically conduits and technological networks—but it also expresses his interest in the subconscious. The red’s dim warmth hums under the darkness of the painting, reminding us of what lies beneath the visible.

We also see the artist beginning to step into new terrain. Untitled (1981) is a stunning painting hung between two rooms at Craig Starr, perhaps a nod to its transitional status. Here, the artist used Roll-a-Tex, an industrial paint additive applied to the painting’s surface with a roller, creating a craggy texture similar to popcorn ceilings and faux-stone facades. Rolled over this surface is a blazing fluorescent red, a hue that does not translate well in reproductions. A sea change for the artist, the color sears the eye and activates the body, insisting that the viewer encounter the work in physical space. Within the red plane are six squares, their sharp edges no longer made by a steady hand, but rather drawn with a strip of tape. Formed by the absence of paint, the squares reveal the unprimed canvas below, but against the electric red they radiate a sickly green.

It’s thrilling to see these early works and examine the elements of Halley’s practice that aren’t yet quite ironed out. The irregularity of his brushwork is not yet streamlined, the fissures not yet filled, and the color palette not yet fully electrified. Experimentation is necessary for every young artist, and in Halley’s case it seems to have laid the groundwork for a lifelong commitment. Throughout Halley’s extended exploration of built enclosures and geometric limits, he has remained an intuitive painter, following hunches in composition, scale, and color. His paintings emerge from this exploratory creative space, always on the verge.