May 23, 2023

Download as PDF

View on Frieze Magazine

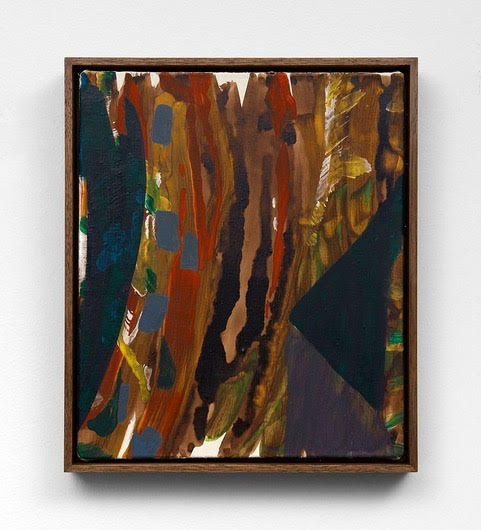

‘Funk You Too! Humor and Irreverence in Ceramic Sculpture’, 2023, installation view. Courtesy: The Museum of Arts and Design; photograph: Jenna Bascom

Was funk art a bona fide movement, or is ‘funky’ just a fragrant adjective? Even in 1960s San Francisco, funk wasn’t exactly a collective effort. Its attitude, as curator Peter Selz described in the essay accompanying his 1967 show ‘FUNK’ at Berkeley Art Museum, spanned artists who explored garish hues, unwieldy shapes, pop-cultural imagery and vulgarity’s limits. Selz called funk an ‘anti-form’ that rejected New York’s cool minimalism for a ‘scatological’, Freud-inflected style – but jokey, so Herr Doktor’s theories became larks. Artists Selz showed – among them Joan Brown, Bruce Conner and Peter Voulkos – disputed his claims. But it wasn’t these established practitioners who needed what funk proffered: instead, Selz gave permission to the bawdy searchers, while offering their art at least the appearance of an intellectual context. And none felt more enabled than Robert Arneson who, with fellow ceramicists Howard Kottler and Maija Peeples-Bright, took funk as a foundation for chimerical, playful and sometimes wilfully amateur work.

Arneson passed down funk through the academy – an essential channel in a medium whose creative possibilities are diminished by pejorative assertions that ceramics are solely the province of craft. A new exhibition at New York’s Museum of Arts and Design (MAD), ‘Funk You Too!: Humor and Irreverence in Ceramic Sculpture’, traces the lines of Arneson’s influence among peers, students at University of California, Davis – notably Sandra Shannonhouse and Richard Shaw – and a younger generation of sculptors, some born after his death in 1992, who have followed his cheeky trail through clay. So much of art today is funky. One wonders: does the description have any enduring meaning?

Critically, MAD’s show reaches past funk’s self-mythologizing to revisit overlooked traditions and draw out its failures. In universities, women were discouraged from learning the firing process, spurring Patti Warashina’s savagely punning sculpture Metamorphosis of a Car Kiln (1971), which comprises a brick oven transforming into a flaming vehicle. Elsewhere, an ornate box of clay candies by Shannonhouse (Candy Heart, 1975) and a pink confection by spiritual successor Yvette Mayorga (Lovers Paradise from the Surveillance Locket Series, 2022) wink at women’s expected role within ceramics as decorators. Colombian-American sculptor Natalia Arbelaez’s Mestizo Arbelaez (2020) mixes terracotta and majolica, referencing how indigenous earthenware melded with a Spanish import. The exhibition, albeit centred around funk, acknowledges that clay’s history is diverse – after all, humans have used it for thirty thousand years, predating bronzework by tens of millennia.

If the titular genre offers common ground to these 26 featured artists, it’s because funk draws loose boundaries between styles. Artists incorporate cultural heritages without shackling themselves to orthodoxies. Southern-born Woody De Othello’s Open Vase (2020), for instance, echoes American face jugs that were likely first designed by enslaved Black people, though De Othello removes the ghoulish miens and leaves only ears – one hardly needs to glance across the room at the protuberant orange auricle of Klown (1978) to recognize Arneson’s own ear fixation. Maryam Yousif was born in Baghdad, a renowned centre of ceramic production, yet Fashion Show Model with Landscape Dress (2021) reaches into other aspects of the region’s history. The character sports a gown modelled on styles popular in 1970s Iraq and a purse inspired by Assyrian reliefs, in which divinities often carry baskets. Yousif wraps it all in an allusion to couture: if funk isn’t a movement, its clarion call for artists to find freedom through sassy recombination still resonates.

It’s easy to put mid-century art on a pedestal (pun funkily intended), yet the surprise of ‘Funk You Too!’ is how younger artists have taken their predecessors’ provocations into fresh terrain. Didi Rojas’s oversized Margiela shoes I Pledge Allegiance to…I’m Baby (2022) and Alake Shilling’s glittery, stuffed-seeming Baby Bear Loves Alake (2021) set funk in a present brimming with consumer detritus. We’re reminded of overflowing landfills and plastic’s ceaseless decomposition – artificial material’s grim futures. The reference is poignant – subtler than the flamboyant pieces might suggest. Funk may be a footnote, but clay – continually forming organically from the earth – will outlast our late capitalist moment, and any art movements to come.