April 26, 2024

Download as PDF

View on The New York Times

Long before painters such as Winslow Homer and Andrew Wyeth arrived in Maine to capture its spectacular natural beauty on canvas, the native Wabanaki people used materials from the landscape to weave black ash and sweet grass baskets, the oldest continuously practiced art form in the state.

“It’s said that our cultural hero, Glooskap, fired an arrow into the black ash tree and our people came dancing out — it’s tied to us,” said Jeremy Frey, a 45-year-old, seventh-generation basket maker from the Passamaquoddy tribe, one of several in the Wabanaki Confederacy.

Frey’s vibrant and innovative baskets — remarkably contemporary forms woven with ancestral knowledge — have caught the attention of the art world and put him at the forefront of a wave of interest from museums, galleries and collectors in the work of Native artists. (This month, Jeffrey Gibson is the first Indigenous artist to have a solo exhibition in the U.S. Pavilion at the Venice Biennale.)

“There was this hierarchy that still sometimes exists within the museum practice of what is art, what is craft, who is an artist,” said Jaime DeSimone, chief curator of the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, Maine. She was a co-organizer of “Jeremy Frey: Woven,” the first solo exhibition of a Wabanaki artist at a fine art museum in the United States. The show will be on view from May 24 to Sept. 15 at the Portland Museum of Art in Maine.

The show, a retrospective spanning Frey’s career of more than two decades, includes 50-plus baskets and will travel to the Art Institute of Chicago — one of several major institutions to have recently acquired Frey’s work for their permanent collections — and the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Conn.

Even 10 years ago, a fine art museum in the Northeast would not have accepted a donation of a Wabanaki basket, according to Theresa Secord, a member of the Penobscot Nation and a basket maker who founded the Maine Indian Basketmakers Alliance in 1993 to help recruit young people to the tradition.

She mentored Frey after he joined the alliance in 2000, when baskets sold at markets near resorts along the coast of Maine for $100 or less. Now, Frey’s baskets sell at the Karma gallery in New York for $20,000 to $100,000, to museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and to contemporary collectors such as Carol Finley, a board member of the Dia Art Foundation.

“We were making our grandparents baskets when Jeremy came along,” said Secord. “He started really refining the practice, crafting new shapes and styles and working differently with the materials than anyone had ever worked before — actually braiding the wood.”

The Portland Museum broke new ground in the art world at its 2015 biennial, where baskets by five Wabanaki artists, including Frey and Secord, were positioned front and center in the opening gallery, “making a statement that these were the original artists here in what we know as the state of Maine,” DeSimone said. “There was not this distinction of us and them — they were just artists.”

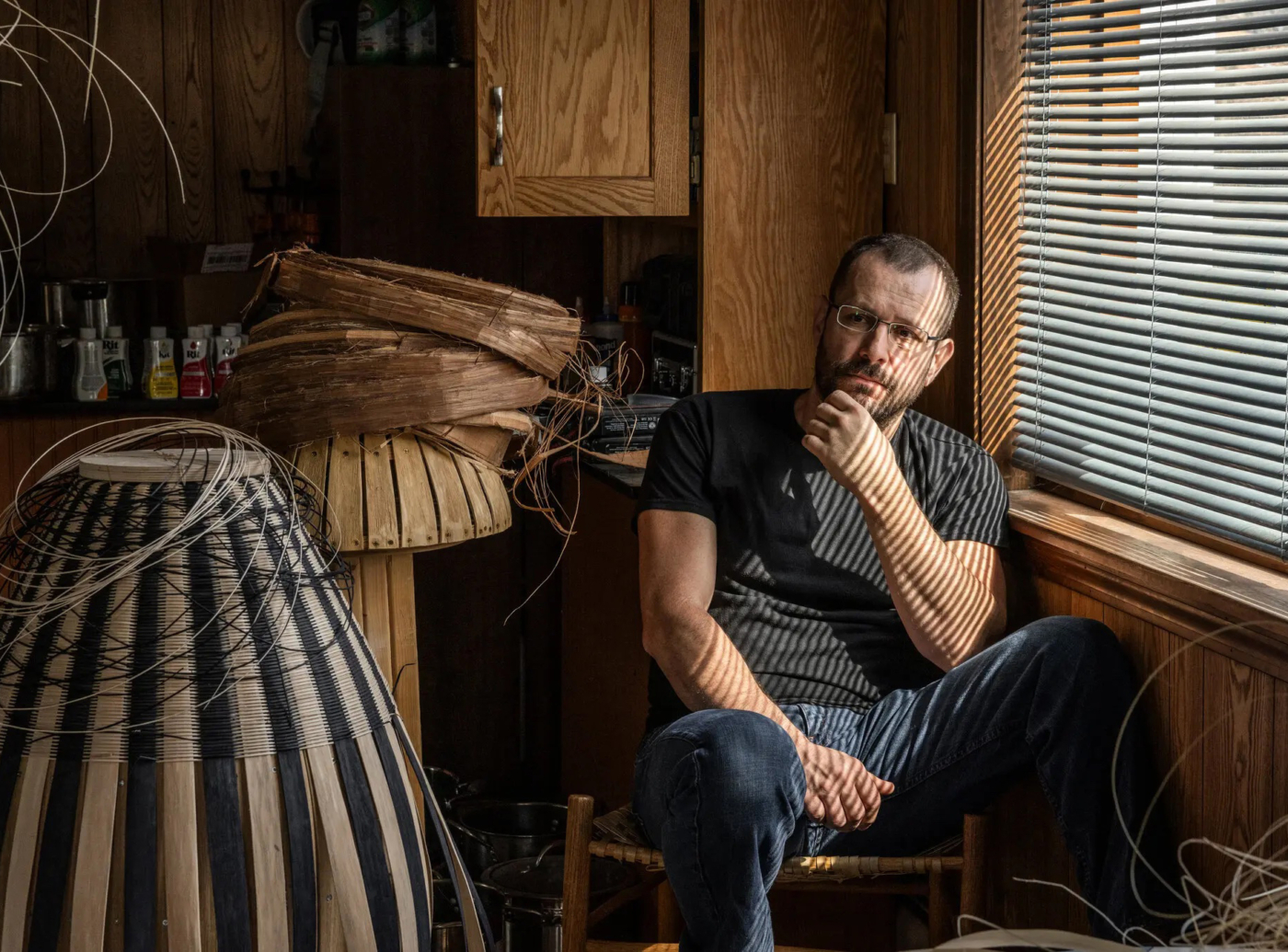

Frey lives with his wife and three children just outside Bangor, about an hour and half from the Passamaquoddy Indian Township Reservation where he grew up in poverty with his mother and two of his three brothers. (He never really knew his father, who is Swiss.) Frey’s grandfather, a fisherman, was renowned for his utilitarian work baskets, typically woven by Wabanaki men; more decorative “fancy baskets” as they are known, traded at markets, were done by women.

Frey’s reinventions have challenged these gendered roles in basket making.

“All I’ve ever wanted to do is be an artist,” said Frey, who made his own toys in childhood with clay and carved wood. As a teenager, he got swept up in the epidemic of drug abuse on the reservation. “I felt like my life was spiraling,” said Frey, who came back to weaving in early adulthood through the guidance of his mother, looking to keep his hands busy as he was getting sober.

His aptitude for basketry quickly gave him a new direction in life. From his uncle, Frey learned how to harvest the right ash trees in the forest — picking maybe one in a 100 — and pounding and processing the logs into long silky smooth strips, which he gauged as thin as one thirty-second of an inch to make finer weave baskets than others were doing.

“I’m always trying to see what the wood can do, what I can do,” said Frey, who’s challenged himself with unconventional color combinations and dynamic contours, mesmerizing patterns and three-dimensional textures, weaving the exterior and interior surfaces — essentially two baskets in one — or scaling them up as tall as six feet.

“They’re sculpture now,” he said. In the Portland retrospective, his latest weaving, a deconstructed basket, appears to spiral into the wall like a vortex.

Brendan Dugan, the founder of Karma, said the enormous interest in Frey’s work had come “almost exclusively from the contemporary art collectors.” Before the gallery opened its first solo show of Frey’s work last year, the Texas-based collector Marguerite Hoffman saw the baskets mounted on pedestals through the storefront window. After knocking on the locked door, she bought one on the spot.

“I’m not normally someone who collects either in the area of crafts or Indigenous culture,” said Hoffman, who chose one of the smaller two-tone forms. “Something about the shape really gets to me, like the curve of a beautiful car or a late de Kooning line drawn in space.”

The Baltimore Museum of Art’s new acquisition “Aura,” with a geometric relief of triangular red points vibrating against a turquoise weave, will go on view May 12 as part of a series of shows called “Preoccupied: Indigenizing the Museum.” In July, the Metropolitan Museum will mount an intergenerational display of recent acquisitions by Frey and Secord together with a painting by Rabbett Strickland at the entrance to Art of Native America.

Frey’s baskets embody not just the final form but “a whole process that involves community history, ties to homelands and a knowledge of local plant life and natural environments,” said Patricia Marroquin Norby, who is Purépecha and the Metropolitan’s first curator of Native American art.

The decimation of ash trees from the Great Lakes to Maine by the invasive beetle emerald ash borer since 2018 is posing a threat to all Wabanaki basket making, something Frey is adapting to in various ways. “Losing the ash, I can’t describe it because it’s not just a material, it’s an identity,” he said.

The artist now harvests twice the trees he needs and puts the other half in storage for the future. He is keen to experiment with new mediums, including weaving with metals like copper, and has completed his first series of monoprints with inked weavings put through the press.

Frey has also made his first video, commissioned by the Portland museum and on view near the end of the retrospective. The camera follows him through the forest hauling logs and transforming them back at his studio into malleable strips and crafting them over months into a labor-intensive basket. When he sets the final form on a plinth in a pristine gallery, the object begins to smoke, then bursts into flames and collapses into smoldering ruin.

Frey wants to leave its interpretation open-ended.

“What does that mean to appear and have a presence and then disappear sort of instantly?” said DeSimone. “You can imagine feelings and realities about Indigenous people here in the United States and life and loss. How can a basket symbolize an entire population?”