May 29, 2024

Download as PDF

View on The Brooklyn Rail

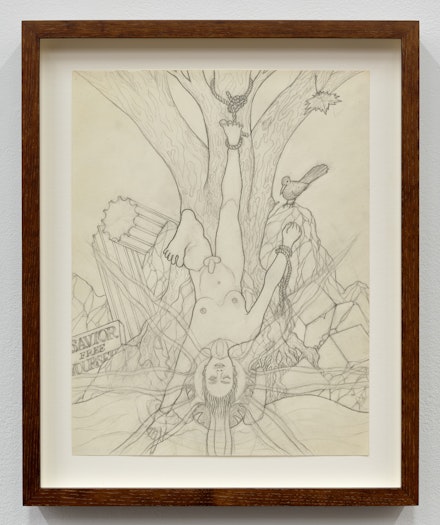

Alan Saret, Suspense, ca. 1999. Pencil on paper, 11 × 8 1⁄2 inches. Courtesy the artist and Karma.

If Alan Saret (b. 1944) were a geological formation, then this show—filling all three of Karma’s venues—would be a voyage to a bedrock composed of several strata. We move from 1975, when Saret was thirty-one, to 2024, and receive a comprehensive sample of his artistic production, excluding his signature wire sculptures. That body of work is deceptive in that we usually look at the overall gestalt of a given piece without considering the composition of the wire itself. We may see cloud-like, flame-like, or vaguely biomorphic formations, but the structure’s atomic components are all but invisible. If we look closely, we see that a work composed of chicken wire, for example, possesses a cell structure, hard geometry.

Not seeing the forest for the trees, seeing only the sculptor Saret, may be the intellectual and personal pretext for this grand scale show, whose title ironically echoes Ronald Reagan’s horrified scream of “Where’s the rest of me?” when he discovers his legs have been amputated in the 1942 film King’s Row. Indeed, Saret’s admirers, familiar only with his wire works may well wonder where the rest of his oeuvre has been hiding. This three-part show should fill in the blanks and generate astonishment among his fans.

The logical place to begin is on 22 East 2nd Street: thirty-four works (drawings and paintings) in a figurative mode reminiscent of Pierre Klossowski, not erotic but highly allegorical. These drawings link Saret to the Symbolist tradition that produced Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Arnold Böcklin. All three of those artists present to the viewer scenes of spiritual life, esoteric symbology, and metaphysical beliefs that defy logic. Saret is as saturated with arcana as they are, always with reference to a process of transformation or metamorphosis. Suspense (ca. 1999) is an 11 by 8-inch pencil drawing representing the Hanged Man from the Tarot pack of cards. The Tarot deck is a complex initiation process, so Saret’s Hanged Man is a species of self-portrait. Hung upside down by one foot, the Hanged Man is between worlds, suffering a purification rite in honor of his own beliefs. That this is how Saret construes the artist (himself) seems confirmed in the mock inscription “Savior Free Yourself” on the left side of the drawing. To be an artist means to live and yet not live in the world of contingency, that is, suspended between worlds. To free himself, the artist must renounce links to the world to find his true niche, must engage in self-sacrifice by devoting himself to his art.

The problem Saret faces as he explores his existence as an artist is to find the appropriate expressive vehicle. The allegories contained in the works displayed in the 22 East 2nd Street space bring forward the problem inherent in images meant to express ideas. Unless we are initiates, the images remain mute enigmas, fascinating but hermetically sealed. In the 172 East 2nd Street gallery, Saret resorts to words. These inscriptions recall Concrete Poetry, where the semantic message is bound up with color and calligraphy. Heart Sun/Clear Expanse (2015) is a double image: in the upper register, in crimson script, appear, one on top of the other, the words “heart,” “sun,” “blazing,” “being,” and “see.” The five words encapsulate a moment of intuition when sensuous experience fuses with intellectual comprehension. The lower register, also composed of five words—”endless,” “through,” “the,” “clear,” and “expanse”—in silvery gray script constitutes the artist’s own intuition of what the experience means. An epiphanic instant becomes eternal by means of inscription. The visitor to this space may also hear Saret himself variously chanting or singing mantras, though only those with super sensitive hearing will be able to hear the words.

In the 188 East 2nd Street gallery, Saret abandons allegory and language. Here we find myriad experiments with geometry, itself both a language and a will-to-power in that it imposes a human order on nature. The temptation to see Saret’s geometric compositions as mandalas is impossible to resist, because Saret is deeply imbued with Indian thought. But whether these works are spiritual maps leading us to illumination or Saret’s way to capture his artistic perception of space is impossible to discern. Of an almost unimaginable complexity, these drawings carry forward Saret’s amalgam of mental intuition and physical representation. An amazing example is Bluebirds and Cardinals in Pairs on the Old Oak’s Limbs (2004), an 11-by-8-inch drawing in colored pencil, ink, and acrylic ink on vellum. There are no birds here, no oak trees, but there is blue and there is red, so the birds have become geometric configurations composed of superimposed squares. Saret appends to the drawing an explanation of such density, it too requires an explanation. If we take the birds and the tree as a point of departure—our perception of nature—then we understand that what Saret has translated experience into geometry. At the center is a black star composed of one square imposed on another. If this is a mandala, it leads us to the enigma of art itself, locked in the artist’s heart.

Saret gave the title The Rest of Me to this tripartite show. Instead of chanting mantras, he might well have belted out that 1931 hit “All of Me, Why Not Take All of Me?” To which we would say, “Gladly.”