August 28, 2024

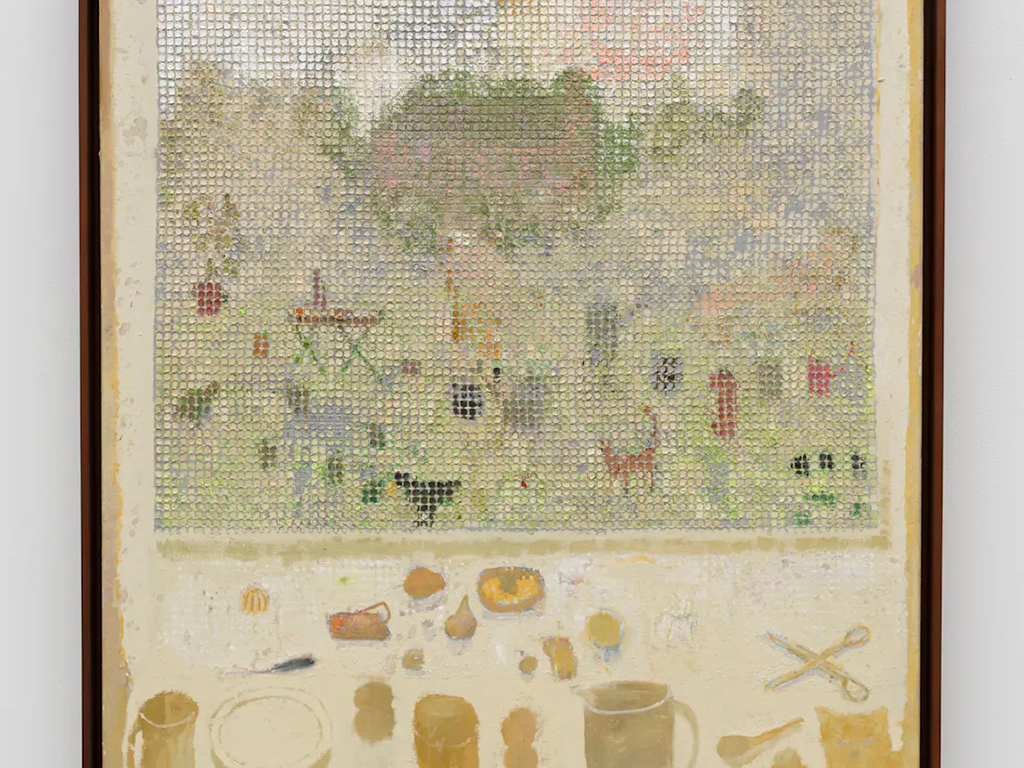

Finally seeing Andrew Cranston’s nuanced paintings in person has confirmed why I continue to find so much other “emerging” painting to be shallow. I am being unfair a bit. Cranston’s work isn’t really emerging, it is just nowhere near as well known as it deserves to be. The pictorial and material depth of Cranston’s painting is refreshing, all the more so because the paintings can seem, at first glance, to come from decades if not centuries ago. But they are both something and somewhere else. (And somehow—magically, let’s say—all twenty-five paintings are dated 2024!) Take, for example, The Invisible man. Before we get to any of the recognizable imagery it may contain, it materially recalls, in a painting-within-the-painting that fills up the top two-thirds of the canvas, Post-Impressionism and the New Image Painting of Jennifer Bartlett and Joe Zucker, not to mention the long and sumptuous history of tapestries. Comprised of a grid of individual impasto-pixels, this inner painting depicts what looks like a grand estate fronted by a lawn populated by an array of leisurely objects. The rest of the composition establishes the illusion that the pixel-grid painting is on a wall in front of which is a different assortment of interior domestic objects, painted in muted shades of yellow, and close to actual size yet larger than the much larger objects in the pixel-lawn above. Of the eight medium to large paintings, it may be the least grandiose, yet I found the exponential manner in which it is built, as well as abstract and representational space it represents, as the star.

That said, while I wouldn’t consider any of the large paintings a failure in any way, collectively they returned me, sans nostalgia, to a way I thought about the strong emerging painting in the mid-1990s, particularly that of Laura Owens and Peter Doig, who, it is clear, was the most impactful of Cranston’s teachers. Back then, every solo show of theirs included a painting that I thought just didn’t work. Rather than provoking an “gotcha” reaction, however, these works proved to be the catalyst for concluding that their work was important and valid. In 1998, starting a walkthrough of Doig’s first survey in front of a particular painting (it gave me, of all things, Andrew Wyeth vibes), the first thing I said was “He’s got to be kidding.” So, then, it’s true that paintings of Cranston’s like The stairs (a dream), and Painting makes nothing happen (what a title!) did come a little close for me to Doig’s 1990s work, but I would not declare them derivative.

I am not suggesting that Cranston’s paintings are retrograde. It very well could be that the mid-1990s was the last moment we could think such a thing. I’ll admit that on occasion, I used the word Mannerist back then, but that would be silly now. The “time” of painting has always moved in multiple directions, and all of that movement (not to mention what we call memory) is incapable of being anywhere except the present.

I think this is why Cranston’s small paintings, especially the ones painted on the detached covers of hardbound books, are so extraordinary. The range included here (there are more than twenty works) is impressive: from the simply exquisite Painting made with my back to an open door, to the surprise of Daddy-long-legs that channels both Giorgio Morandi and Forrest Bess (somehow), to the wit of What makes a Glasgow home so different, so appealing? which invokes the most-known collage of the legendary yet still under-appreciated Richard Hamilton. Distributed across the four walls of Karma’s smaller gallery, they provoked a surprising association for me: the stunning scene in the breathtaking film Interstellar (2014) in which Joseph Cooper (played by Matthew McConaughey) communicates from the interior of a black hole with his daughter—in the past, in her bedroom, when, by the way, he was also in the house—by making the books on her shelves move in the patterns of Morse code to send the message that will rescue him in the far, far future. Cranston’s work just might have convinced me that all of that has something to do with painting.