September 3, 2024

Download as PDF

View on Artforum

Alan Saret’s “The Rest of Me” was revelatory. Exhibited across Karma’s three East Village locations, some 180 illustrations and paintings surveyed an ongoing, spiritually infused body of work by an artist perhaps better known, if somewhat unwittingly, as a central figure of New York’s Process and post-Minimalist scenes of the 1960s and ’70s. Pulling from Eastern and Western religions and philosophies alike—notably Hindu and Buddhist soteriology—this show revealed an artist who for several decades has been exploring the mutability of form and materiality as a path toward self-transformation. This presentation, in its dizzying displays of figuration, geometric abstraction, and textual symbolism, simultaneously enriched and challenged assumptions regarding Saret’s legacy.

Root Deep Rock Pool and First Turns Being Whole Alive, both 2014—Saret’s dharanis, or Buddhist chants and mantras—are from a group of brightly colored text works on paper rendered in the artist’s precise calligraphic hand. These transcendent epistolary drawings called to mind the Tibetan Buddhist–infused and language-based art of the late John Giorno who, like Saret, believed in the spiritual power of incantatory recitation. Importantly, the dharanis are more than just spiritual exhortations of “Be here now,” à la Ram Dass; for Saret, simply reading aloud from these pieces can open the mind’s receptiveness to higher planes of awareness and being.

A selection of figural drawings and paintings, some of the earliest works on view, depicted the artist’s polymathic interest in religious esoterica—think British occultist-cum-artist Austin Osman Spare combined with the Upanishads. In the graphite drawing Dual Dance, 2001, Adam- and Eve-like figures sashayed hand in hand with Lucifer and a cherub, while in the large oil painting Great Winged Glory, ca. 1982–83, an effulgent alary orb seemingly pulled what appeared to be a woman out from a dark void. Elsewhere, the solitary and barefoot subject of Wind Walker, 2001, traversed a scrubby landscape under a bright sky of jagged evanescent clouds, evoking the lung-gom-pa long-distance runners of Tibet who, according to one Western lama, were able to cover vast distances “while hardly touching the ground.” Ironman with the aim of bodhicitta.

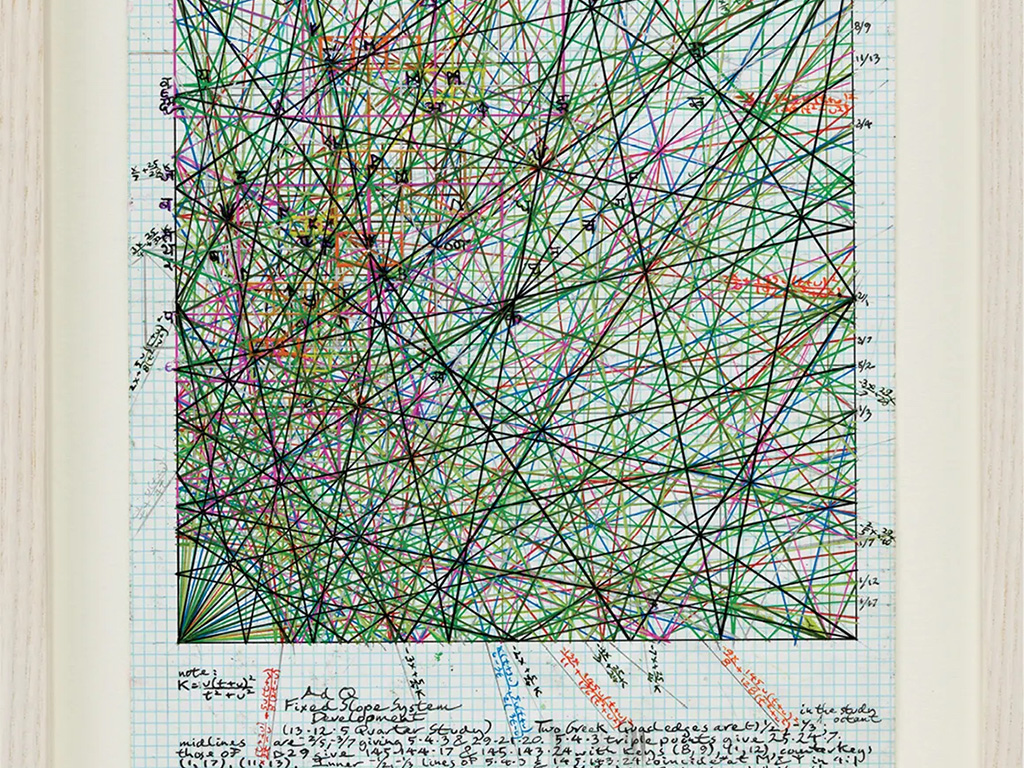

Saret’s geometric abstractions on paper, many of which are titled with the prefix AD Q, remind me of Guatemalan painter Alfred Jensen’s nonobjective works that utilize ancient Mayan numerology and belief systems. In pieces such as Ad Q Fixed Slope System Development, 2007, and Circumcircle System of 13·12·5, 2006, Saret renders lines and forms in dense, overlapping layers, accompanied by handwritten mathematical formulas and symbols, all executed with a chromatic assortment of inks, acrylics, and pencils. Like Pythagoras and Fibonacci, Saret has followed his interest in numbers to find a mystical corollary in the infinite and the underlying rules that govern the universe in all of its illusory, incomprehensible glory. Indeed, at the very end of the computation accompanying Greek Quad Midline & Diagonals, 2007—a frenzy of equations, connecting lines, and shapes—Saret simply writes, LET IT GO, voicing a realization, perhaps, that many of life’s mysteries should stay that way.

What became evident in “The Rest of Me” was the depth of the artist’s long-running dialogue with Western and Eastern theologies. Saret was never tied to one movement or school—he refused to be included in the 1969 group show “Anti-Illusion: Procedures/Materials” at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art on the grounds that his work was very much concerned with the transitory, the phantasmagorical. Like the gurus and sages who inspired him to look beyond and within, Saret has filled his work with prophetic, incandescent magic.