February 2025

Download as PDF

View on Artforum

Jeremy Frey’s meticulously woven objects, which here included baskets as well as wall-based sculptures, reveal a dizzying level of technical fluency. Each one is crafted from the supple bark of the black ash tree (which the artist directly harvests from the land surrounding his studio in Maine) and woven in accordance with Wabanaki basketry techniques, an art form passed down through Frey’s family for generations and one that predates the colonization of New England by millennia. Throughout his exhibition, Frey both celebrated and deconstructed the language of the Wabanaki vessels, employing its signature patterning to create prints and other abstract shapes that disrupted the closed form of the basket, and staking out a more mutable and at times esoteric vocabulary in turn.

While process isn’t synonymous with meaning, an understanding of the intricacies of Frey’s laborious technique illuminates readings of his work. Here, each notch and gesture originates with the black ash, a deciduous tree that features prominently in the culture of the Wabanaki (a collection of five Indigenous tribes including the Passamaquoddy, Frey’s ancestral group). According to tribal mythology, when the heroic figure Glooscap shot an arrow into the tree’s woody body, it catalyzed the birth of the Wabanaki people. The tree functions as a conduit for creation in other ways as well. Unlike other North American trees, its growth rings lack the pulpy fibers that typically fuse concentric layers of bark together, and when a fallen trunk is carefully pounded, its bark can be split apart to create highly flexible sheaths that are ideally suited for weaving. This material lineage positions Frey’s objects in unique somatic relation to the Passamaquoddy landscape: A work such as Presence, 2024, for example—a tall lidded basket ringed with protruding scarlet spikes (a signature motif) and thin bands of turquoise—indexes the ecological conditions that nourished its existence, evidenced by the symbolic arboreal growth rings reflected in its weave. Furthermore, its columnar shape, echoed by baskets such as Eden and Specter, both 2024, the latter of which also includes sharp, knifelike protrusions, alludes to a cylindrical trunk, perhaps venerating the tree’s native form.

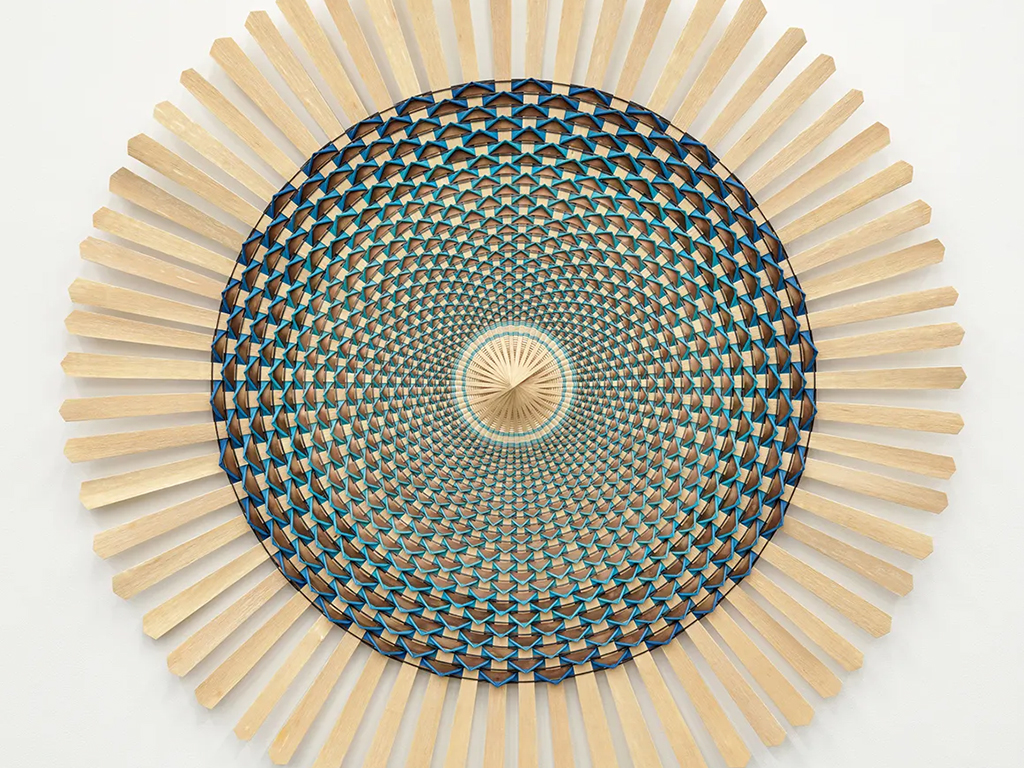

In the exhibition’s titular work, Unbound, 2024—a monumental, wall-based weaving—the skeletal structure of the vessel is flattened and splayed open, revealing the magnanimous architecture of the underlying weave. The object adopts a starburst form: A soft pyramidal mound is orbited by concentric rings of cerulean spikes that radiate outward; they appear tiny in the center and grow exponentially larger at the margins, producing the hypnotic illusion of a rippling portal. The unpainted wooden splints that emerge from the outer edges of the weave suggest that this tondoesque form could expand infinitely, setting up an intriguing dialectical relationship with the closed and completed baskets exhibited nearby. Elsewhere, small sections of flat, framed weavings (e.g., Distraction, 2023) functioned as matrices for a series of relief prints on paper; these works included both linear and circular compositions and were often set against a prismatic ground of chine collé (e.g., Untitled, 2023). Here, errant fibers, ghostly traces of wood grain, the syrupy texture of ink, and the pliant geometries of the woven form—over, under, behind, between, and through—coalesce to form ephemeral tableaus that are both indebted to and independent from their unique cultural origins. Much like the Wabanaki basket and the black ash tree, these immaculate weavings and their printed companions serve as material ciphers for one another, reciprocally reenacting their intertwined histories.

In a 2023 video interview, Frey remarked that weaving was “one of the languages my tribe speaks, and I am one of the carriers of that language.” Embodying this analogy, his objects, in addition to being formal sculptural achievements, both contain and transmit important vernacular information. As vessels removed from their traditional functions, Frey’s baskets ultimately serve as receptacles for the intergenerational transference of skilled labor and knowledge, the preservation of which crucially defies colonial dogmas of assimilation and eradication.