September 1, 2025

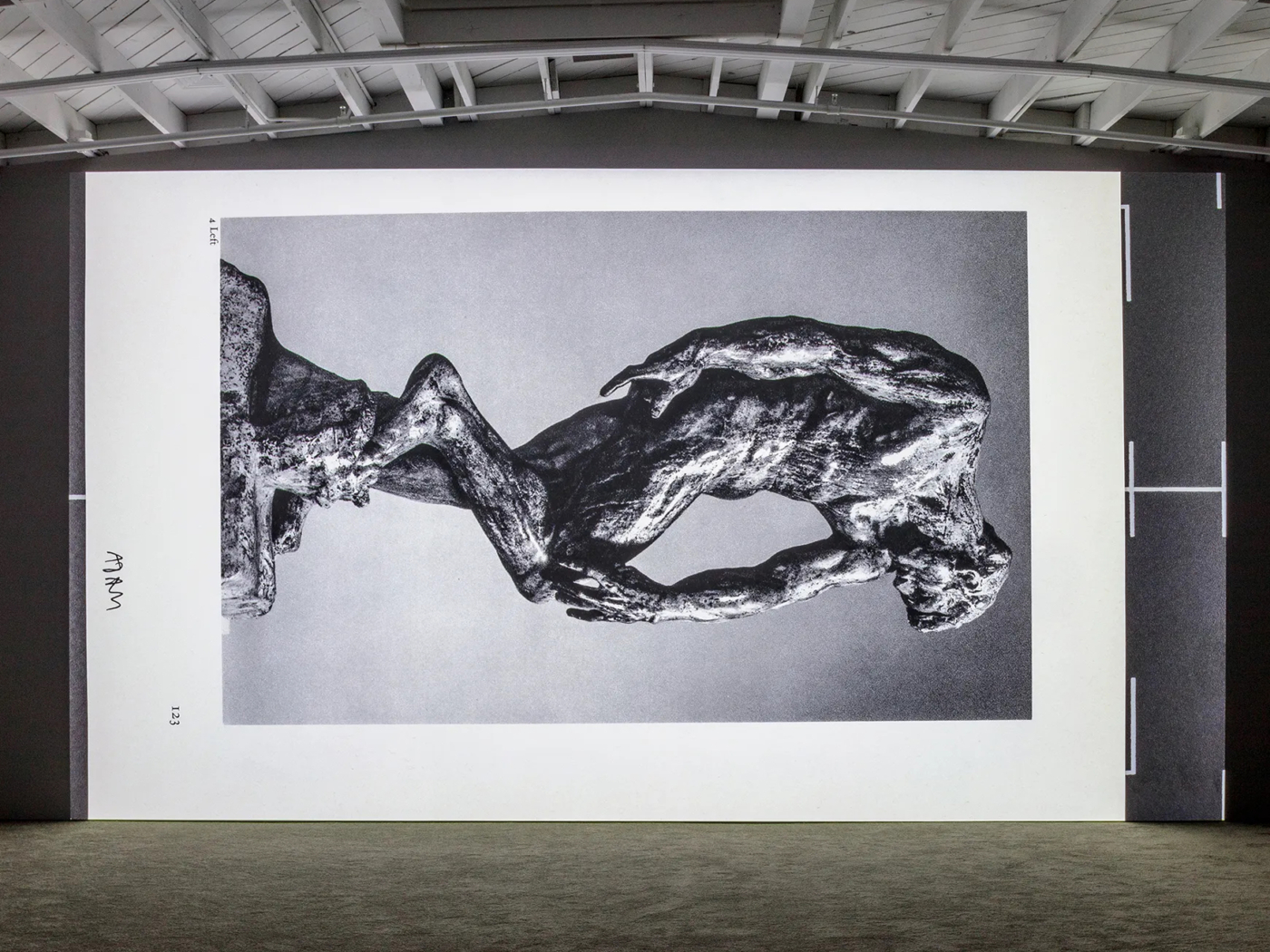

THE VIDEO WORK SIDEWAYS THOUGHT, 2020–22, by Mungo Thomson comprises one part—or, as he puts it, “volume” (number 5, in this case)—of his expansive “Time Life” series, begun in 2014 and ongoing. Sideways Thought is generally devoted to the work of Auguste Rodin and, more specifically, to how the sculptor’s practice appears in print media. The pictorial material included in the video was gleaned from some fifty art catalogues, their number large enough to suggest comprehensiveness, although it doesn’t come anywhere near representing the totality of publications on the sculptor’s work—a goal that would in any case be unreachable, since new entries continue to appear on a regular basis. Thomson’s production process is relatively straightforward: He cuts pages from their bindings and shoots them on a copy stand with a Canon 5D camera connected to a Dragonframe stop-motion animation program. On-screen, static pictures of static objects are thus made to move, or rather, since all of these objects have been photographed from multiple angles, in different spaces, and under varying conditions of light, our eyes are set into motion around them. Simple enough, yet the viewing experience is much more complicated, by turns enthralling and deeply disquieting. It is uncanny in precisely the sense highlighted by Freud, prompting anxious questions as to whether something dead has come alive, and vice versa. State-of-the-art animation techniques here collide with primal intuitions of animism.

In Sideways Thought, discrete works by Rodin are merged into a singular, monstrous entity, a lump of prima materia continually undergoing decomposition and recomposition. One might be reminded of the malleability that defined Art Clokey’s clay character Gumby, a staple of children’s television programming during the 1950s and ’60s, only now the process unfolds without beginning or end: Ceaselessly, sculptural form pulsates and mutates. As we are never returned to any figural baseline, our eyes are increasingly ungrounded. Only in the technical artifacts—which include the registration lines of the copy stand, the skewed edges of pages, the fragments of text and annotation surrounding the pictures, and ultimately the grain of the photograph—do we find anything to firmly latch on to. These details are all reproduced in extremely high resolution and projected at large scale, a reminder that every illusion on offer stems from concrete “facts on the ground.” Remain focused: The main event of the work is mediation.

Other entries in Thomson’s “Time Life”series relate to exercise, cooking, flowers, etc.—an assortment of topics deemed by the publishers of Time-Life Books as essential to individual cultivation at a particular moment in history. Together, they point back to a midcentury period of inflection in the logistics of mass culture, particularly in the United States. They place us squarely in the midst of the “American Century,”a time of booming prosperity, national pride, and seemingly unlimited cultural clout.1 Abstract Expressionist painting and jazz were being exported worldwide and yet, against this effervescent backdrop of free-form cosmopolitanism, the figure of the uncultured, uncouth, “Ugly American” remained stubbornly present. This might well have been Time-Life’s target audience; to put it bluntly, its books were designed to counter our incipient provincialism, and nowhere more sharply than in the art-related titles. These offered a tour of the art-historical horizon to an audience that, for the most part, had no access to the works collected in the cultural capitals. Sold on a subscription basis, books devoted to the old and new masters would arrive every few months in the homes of those marooned in “flyover country,” delivered by mail like emergency rations. One could say that the promise of André Malraux’s “museum without walls” was here fulfilled to the letter.2 But the counterargument is no less valid: Reducing fine art to just another delectable item of staycation tourism, this virtual show-space might have advanced cultural taste no farther than the middlebrow mark.

Between 1966 and 1970, Time-Life released its Library of Art special collection, a corpus of twenty-eight volumes, introduced (as per usual) one at a time. Among these was the 1969 title The World of Rodin, 1840–1917. While this book was certainly a prime catalyst in the making of Sideways Thought, Thomson’s work reaches well beyond the imagery that appears in its pages. This marks a departure from his earlier videos, which tend to hew more closely to a single source in the imprint.3 The exorbitant proliferation of such imagery is here delivered in a form that might be termed at once cinematic and not, something like a very fast-turning slideshow. The upshot is undeniably a moving picture; however, animated at eight frames per second—well below the once-optimal number of twenty-four (now sometimes ratcheted up to sixty and even 120)—it falls short of that physiological sweet spot where the succession of distinct imagistic units is merged into a seamless flow by way of the persistence of vision.4 Rather, Sideways Thought plumbs a sour spot, and does so with great precision. Its momentum is herky-jerky, staccato. Between every frame a disjunctive gap intrudes, subdividing the whole back into its parts, and thereby confronting the viewer with the plethora of copy culture, a barely manageable immensity of data.

If we can relate Thomson’s video to cinema in more than a metaphorical sense, then it would have to be a highly fragile sort, always accelerating while at the same time devolving toward the stasis of its photographic building blocks. It is a psychologically taxing experience; one struggles with it but then also occasionally surrenders in a kind of blissed-out exhaustion. Numerous precedents for Thomson’s approach can be cited from the annals of the avant-garde and/or underground, including such works as Wallace Berman’s Aleph, 1956–66; Stan Brakhage’s Mothlight, 1963; and Tony Conrad’s The Flicker, 1966. That the heyday of “hypnagogic cinema,” as some have labeled it, intersects with that of the Time-Life books lends this project a near-irreproachable conceptual basis. No less fortuitously, the concept can quickly be set aside. The impact of Thomson’s work is as overwhelmingly embodied and visceral—and also, I will add with some trepidation, mystical—as that of his forebears.

There is a distinctly anachronistic quality to these proceedings, and this too contributes to their uncanny effect. But whereas the filmic auteurs mentioned above drilled down on the stroboscopic flashing of their projectors, always set at the same rate, as a means of synchronizing the viewer’s breathing, pulse, and synaptic firing with the flow of images on-screen, Thomson commands a much more versatile technology. Here, because lenses remain open, the hypnagogic timing is adjustable. In the “Time Life” works the image not only moves but vibrates; it carries a rhythm. These videos are composed either in response to a soundtrack (as is the knot-tying-themed Volume 6. The Working End, 2021–22, which is edited to the beat of Pauline Oliveros’s 1974 percussion piece “Single Stroke Roll Meditation”) or else they instigate it (for instance, Volume 16. FOLK2NS, or The Encyclopedia of Guitar Chords, 2025, in which the imagery literally scores the soundtrack, performed by Lee Ranaldo). The timbrally meandering electronic pulse in Sideways Thought was generated by Ernst Karel to the tempo of the footage. Reminiscent of Steve Reich’s metronomic Minimalism and equally of the thrum of scanning devices, its design came in reply to the artist’s demand for “an MRI you can dance to.”

Upon his emergence, right around the start of the aughts, Thomson was often characterized as a late-stage responder to the so-called Pictures generation. This was a period when terms like media hacking and culture jamming had begun to displace the old-school “appropriation.” Plundering the reserves of mass-market entertainment as well as avant-garde art, he has always deployed both erasure and archival accumulation as signature tactics. For instance, in The American Desert (for Chuck Jones), 2002, the characters from “Road Runner” cartoons are excised to leave behind just the scenery, a succession of moving landscape tableaux. In Untitled (Time), 2010, a video that more directly relates to the one under discussion here, every Time magazine cover, from that of the first issue through that of the then-latest, scrolls by at an impossible pace. We are dealing with the life of Time, approaching information and knowledge from the outside, at an angle at once philological and absurdist.

Clever is a term that is sometimes used to describe Thomson by his detractors. In art, it carries a decidedly unflattering tone. Yet the cleverness on offer here opens every “one liner” interpretation to a radiating constellation of lines that is pretty much inexhaustible. One of these has to do with the fact that, as Rosalind Krauss notes in her 1981 essay “The Originality of the Avant-Garde,” Rodin was among the first in his field to work perfectly in sync with the regime of technical reproducibility. “Now, nothing in the myth of Rodin as the prodigious form giver,” she writes there, “prepares us for the reality of these arrangements of multiple clones.”5 Nevertheless, it is evident that Rodin multiplied his sculptures in edition copies circulated throughout the globe, much like photographs. This analogy is central to Krauss’s argument.6 The connection between the dispositifs of these two media—one involving casts and molds, the other negative film and positive prints—deserves much more attention than I am prepared to give it here, but let’s keep it in mind. Another tangential line worth pursuing: Rodin made ample use of photography proper in his figural renderings. In other words, the emphatically hands-on aesthetic for which he is known took shape in the shadows of the hands-off. By the end of his life, this artist had amassed an archive of some seven thousand photographs, many of them featuring nude models, which he employed in his studio process. In addition, Rodin regularly commissioned photographs of his sculptures, thus twisting this intermedial exchange into a feedback loop.7 One more line, this one pushing back against the last two: Rodin both embraced photography and decried it. He never went so far as to renounce it, as the record amply proves, but neither did he accept its vaunted realism without reservation. Rather, one could say that his goal was to mobilize the medium’s limits, these having everything to do with its incapacitating relation to movement.

In a famous dialogue with the critic Paul Gsell, Rodin reportedly said, “People in photographs suddenly seem frozen in mid-air despite being caught in full swing: this is because every part of their body is reproduced at exactly the same twentieth and fortieth of a second, so there is no gradual unfolding of a gesture, as there is in art.”8 That this “gradual unfolding of a gesture” might have been made up by the artist, and hence potentially erroneous, is suggested in Gsell’s rebuttal, as is the idea that the camera is incapable of any such fault. “So,” he responds, “when art interprets movement and finds itself completely at loggerheads with photography, which is an unimpeachable mechanical witness, art obviously distorts the truth.” “No,” insists Rodin. “It is art that tells the truth and photography that lies. For in reality time does not stand still.” This exchange is quoted at the very start of Paul Virilio’s 1994 book The Vision Machine, where it leads into an excursus on the automation of imaging and, moreover, seeing. For all their quibbling over questions of reality versus falsehood, the sparring partners drive at an insight that is central to Thomson’s project in general. Ultimately, it has to do with energy and the distinction between its patient aesthetic conservation and its abrupt technical capture and suspension.9

It is on this point that Thomson’s cleverness takes on a metaphysical tint, for these are concerns that can be traced back to ancient philosophy.10 The “Time Life” videos enjoin us to revisit such thoughts from the perspective of a picture industry that has, in the interim, undergone mechanization, electrification, and, finally, digitization. What is at stake today is the conversion of all images to a single standard of distribution. These once appeared in stand-alone works of art, either here (where I can see them) or there (where I cannot). Later, they came to be circulated more widely via editioned prints, photographs, newspapers, magazines, films, and TV. At present, they exist in one place, on a screen that folds all these formerly discrete modalities together. A good number of the Time-Life books are now available on such digital platforms as the Internet Archive. Somewhat ironically, Thomson’s studio process thus parallels a much broader (industrial) method, whereby books are systematically manipulated by robotic devices, their pages shuffled at great speed beneath a lens. Volumes are often destroyed in the course of their digital preservation, as is the imagery they contain. Now that these all are composed of exactly the same “elementary particles,” they can, in a sense, communicate with one another and, further, generate novel images through their algorithmic interaction. This can now happen at nearly the speed of light, which is not to say that the results are necessarily invigorating. That the current stage of “the age of technical reproducibility” is one equally prey to the forces of acceleration and inertia is a sense Sideways Thought renders acute. This is very rapidly becoming “the new normal,” yet Thomson’s work keeps us auspiciously estranged. Rodin’s effort to distill entire bodily movements (or gestures) into a single pose—his pushback against their sudden arrest in technical imaging—is one that we in effect replicate as viewers. Anything that moves in the imagistic pile-on of Sideways Thought only does so in our eyes, differently in every eye, but always here and now, in this space and at this time—a singular experience in which invitation to deep reflection collides with the invocation of fugue states. What more could you want from a work of art?

NOTES

1. The “American Century” was announced in a February 1941 issue of Life magazine by its founder, Henry Luce, in an editorial piece urging the nation to reconsider its isolationist policies and engage in the conflict of World War II. This language is resumed in a Time-Life book series published retrospectively in 1997: “Our American Century.”

2. The phrase museum without walls is derived from the first chapter of Malraux’s book Voices of Silence, which was originally published in three volumes under the title The Psychology of Art between 1947 and 1949. A meditation on the promise of photography as an aid to art appreciation, it preceded the first Time-Life title by a little over a decade but partakes of much the same zeitgeist.

3. As Thomson explained it to me, “Because Sideways Thought required so many more books on Rodin than Time-Life offered, I released Time-Life books as a parameter for the series and, after that, any bound printed matter was fair game.” Nevertheless, the publisher’s name has retained its place in his titling. One can infer that it remains a central point of reference for everything that follows.

4. This time signature was also chosen because hard-copy books are scanned at this same rate when digitized—eight pages per second is the rate scanned by the BGS-Auto at the University of Tokyo.

5. Rosalind E. Krauss, “The Originality of the Avant-Garde,” in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (MIT Press, 1991), 155.

6. In this passage, for instance: “Like Cartier-Bresson, who never printed his own photographs, Rodin’s relation to the casting of his sculptures could only be called remote.” Krauss, 153.

7. Interestingly, this practice begins in a quasi-legal context, as is related in the following article on the website of the Musée Rodin in Meudon, France: “In 1877, his submission to the Paris Salon, The Age of Bronze, was the subject of huge controversy. Its critics accused Rodin of not having modelled this male figure, but of having used a life cast. The sculptor reacted by employing photographer Gaudenzio Marconi, who supplied art students with images, to take a series of shots of both the plaster version of The Age of Bronze and Auguste Neyt, the model who had posed for the work, so that they could be used as proof in his defense.” See “Rodin and Photography,” Musée Rodin, accessed July 9, 2025, musee-rodin.fr/en/resources/rodin-and-arts/rodin-and-photography.

8. This and the following quotes are derived from Paul Virilio, The Vision Machine, trans. Julie Rose (Indiana University Press, 1994), 1–2.

9. I am employing some of Rodin’s language here: As he says to Gsell, “If the artist manages to give the impression that a gesture is being executed over several seconds, their work is certainly much less conventional than the scientific image in which time is abruptly suspended.” Rodin, in Virilio, The Vision Machine, 2.

10. Aristotle, for one, placed the distinction between actual and potential energy at the core of his thinking. In his De Anima, we encounter the somewhat obvious but still striking observation that energy is extinguished in its actualization whereas its withholding as potential is outwardly akin to impotence. Nevertheless, without the latter the former could not arise. Potential is the animating principle, which the Latin term anima relates to the soul. Aristotle, De Anima, in The Basic Works of Aristotle, ed. Richard McKeon (The Modern Library, 2001), Section 5, 564–67.