August 29, 2016

Download as PDF

View on Sotheby's

NEW YORK – As an Ohio native, Keith Mayerson couldn’t help but feel inspired by LeBron James leading the Cleveland Cavaliers to a long-awaited victory at the NBA Championship this past June. “Although I spent much of my childhood in Colorado, I was born in Ohio and am a ‘Buckeye’ at heart,” he says. “I love the city and am very at home artistically there.” Now, the event that captured so many people’s imaginations will be celebrated in Mayerson’s new painting The Block, to be auctioned off at a benefit to support MOCA Cleveland on 9 September. The Block will also be on view at MOCA Cleveland as part of Mayerson’s upcoming exhibit, The American Dream. We spoke with the artist about sports, modern American heroes and the importance of supporting public art below.

KEITH MAYERSON AT WORK ON THE BLOCK. PHOTO BY JESSE CARMODY.

Why did you decide to make this particular moment from the 2016 NBA Finals the subject of your painting, The Block?

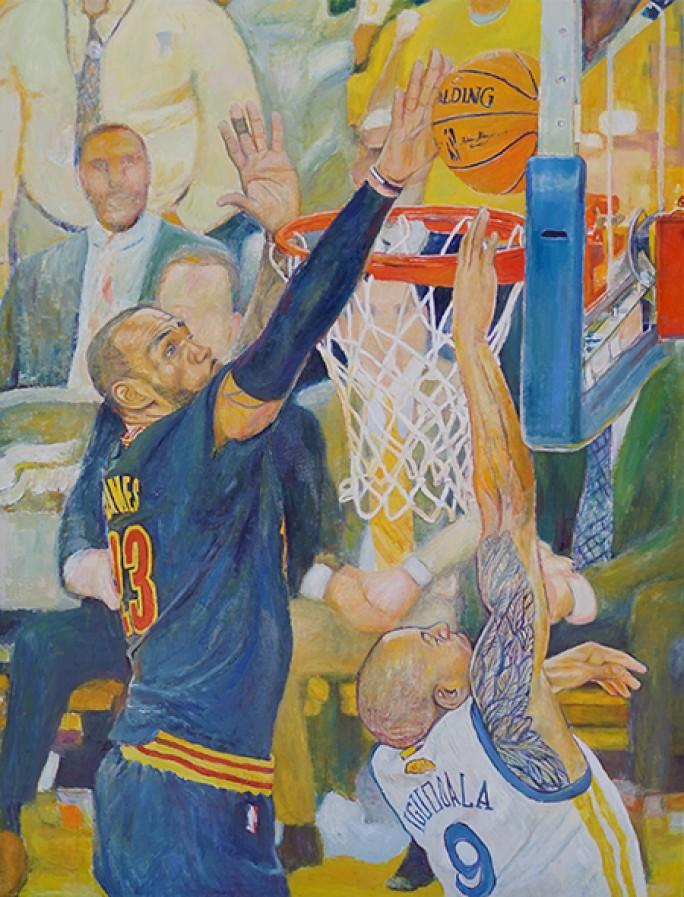

Like Elvis or the Beatles appearing on Ed Sullivan for the first time, when the culture changed the instant they were broadcast across America, The Block was a moment that changed the history of sports. The Cavaliers and the Warriors were in a deadlock during the last game of the NBA Finals, and LeBron saved the game with one of the most amazing blocks in history. Stephen Curry and Andre Iguodala were on a fast break to grab the lead, but then LeBron pinned Iguodala’s layup into the backboard. LeBron, a Ohio hometown hero raised in Akron, rose to acclaim playing with the Cavs, and in a highly controversial decision, left the Cavaliers for the Miami Heat in 2010. However, the prodigal son returned to Cleveland vowing to make them champions, which he achieved with this iconic moment.

Could you talk a bit about your creative process behind The Block?

Although I’ve created many different kinds of paintings over my career, today I paint primarily from photos. I enjoy culling information from them, both in terms of content and emotional atmosphere. Whether I’m working from images appropriated from culture, or from my own personal photos, I particularly like the moment that only the technology of the recorded image can generate from a second frozen in time. I think it’s my job to bring another life to photographic images, both by looking at all the information recorded and by generating feelings that can spill out of the brush along with the conscious intentions of the artist.

KEITH MAYERSON IN HIS STUDIO.

Your exhibition at the 2014 Whitney Biennial, My American Dream, dealt with a lot of optimistic American iconography (Superman, Abraham Lincoln, Marvin Gaye, Annie Oakley, The Wizard of Oz). How do athletes like LeBron James fit into that narrative?

LeBron truly is one of the amazing contemporary icons of the American Dream and everything it can represent. Beyond mere ideology, he shows how someone can raise themselves from dire circumstances to achieve their goals, create a satisfying life for themselves and their family, and hopefully make the world a better place in the process. Although I love fictional characters and how they can serve as models and myths for people to follow, the real human individuals that have strived and achieved to make a difference are the ones I most admire.

A lot of your work also speaks to comics. Is there something about sports in general that appeals to our interest in heroes?

Athletes are real-life superheroes or “meta-humans” in that they are able to move their bodies to achieve higher goals in ways that normal humans can only dream about. It’s exhilarating, for instance, to watch the Olympics, and those athletes and their work ethics can serve as excellent models for anyone who wants to “achieve the impossible.”

KEITH MAYERSON, THE BLOCK, 2016.

You’re donating The Block to MOCA Cleveland’s benefit auction on 9 September. Why do you think it’s important to support public institutions and museums?

I am a populist at heart, and want to bring my work to “the people.” The world of fine art is still too rarefied, and it is my desire that everyone can experience art in the same manner they can other genres of cultural entertainment. Important institutions with excellent programming such as MOCA Cleveland are intrinsic to reaching out to communities that otherwise might not have access. I love museums in general, and hope that everyone can also enjoy the edifying riches that these institutions can offer. Art is language, and language is power, and I feel fortunate to live and make art in a time where we are sensitive to the agency of all people to be able to not only have the space to make art, but also the space to exhibit and enjoy the output of others to generate real feelings, thoughts and change to make the world a better place.