April 1, 2021

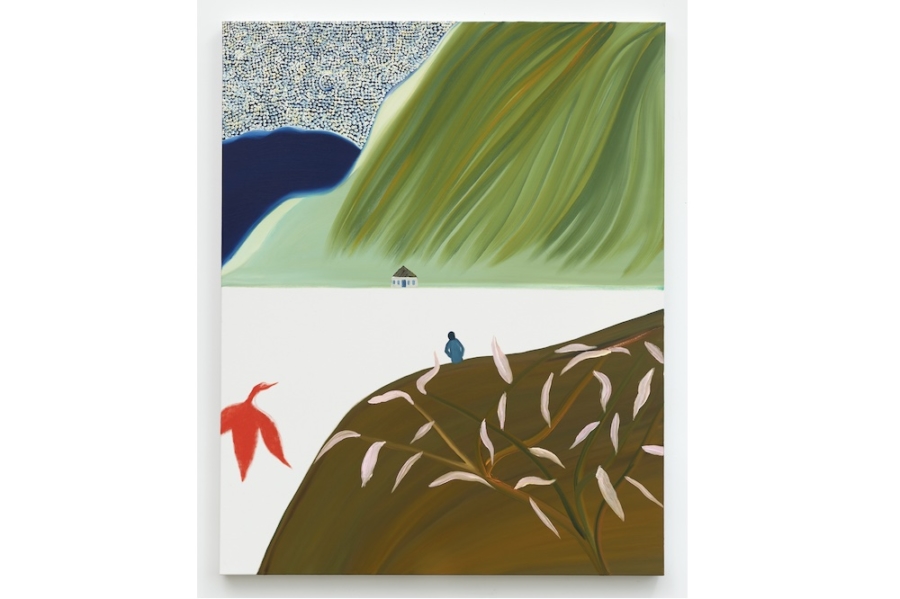

Matthew Wong, See You On the Other Side, 2019. Courtesy of the Matthew Wong Foundation and Karma, New York.

In Matthew Wong’s oil painting See You On the Other Side (2019), a figure in blue stands at the edge of a frozen landscape and gazes out at a house beside a mountain. A red bird hovers just off shore, looking toward the figure. The horizon line divides the composition into two separate spaces; it seems impossible for the figure to traverse the white abyss. We learn from psychoanalysis that a distance that cannot be collapsed is the hallmark of desire. For Wong, irreconcilable distances evoke a sense of perpetual isolation and the longing to be elsewhere.

Wong worked at the intersection of inner psychology and exterior expression, troubling any simple explanations for the tension between them. He constructed paradoxical spaces that, rendered in landscapes and domestic scenes, go deep into the psyche while looking outward to the fields of Western and Chinese painting, pop culture, and contemporary art. Wong was born in 1984 in Toronto, Canada to Chinese parents and grew up in Hong Kong. He studied cultural anthropology at the University of Michigan before moving back. After a few years of working at office jobs, his interest in writing poetry developed into a photography practice, and he pursued his MFA in photography at the City University of Hong Kong’s School of Creative Media. In 2013, after graduate school, he began to paint and draw, teaching himself through his own studies at the Hong Kong Public Library and via social media. He was a self-described “omnivore for sights, sounds, and ideas” and painted by improvisation, instinctually following an emotion, image, or memory and working it toward the formation of a composition. Using social media as a platform, he began showing his work on his Facebook page and built a community within the mainstream artworld by engaging in online discussions with gallerists, critics, and artists on platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Tumblr.

Despite his burgeoning online presence, Wong lived a somewhat solitary life. With his parents he moved from Hong Kong to Edmonton, Alberta in 2016, and painted prolifically in between taking long walks and spending time at his local coffee shop. Wong connected with the New York gallerist John Cheim while chatting on the Facebook page of New York magazine’s art critic Jerry Saltz, and Cheim began posting Wong’s work on his own Instagram feed. That same year, Wong’s work came to the attention of curator Matthew Higgs, who included Wong’s work in Outside, a group show presented by Karma Gallery in Amagansett, New York. Wong’s paintings immediately attracted interest. Following a widely-lauded debut solo show at Karma Gallery in 2018, Wong’s position became solidified. Saltz wrote that Wong’s show was “one of the most impressive solo New York debuts I’ve seen in a while.” Subsequent exhibitions at Massimo di Carlo in Hong Kong, Independent New York, and Karma drew critical and commercial attention. However, Wong continued to struggle with his mental health, and in October of 2019, at age 35, he took his own life, leaving behind a shocked and saddened community that is still grieving his loss.

After his passing, the value of Wong’s work began to rise exponentially: in October of 2020, his painting Shangri-La (2017) sold at Christie’s for $4.5 million, more than four times above the asking price. Narratives about his status as a self-taught “outsider genius” and his swift rise to artworld fame have contributed to a distinct mythology around his work that seems caught up in biography, amplified by the frenzy of market interest. These discussions within the press have primarily been circulated around his exhibitions, and by Karma Gallery, who represent him. Karma has published several significant catalogues of his solo shows, the most recent accompanying Postcards, an early 2021 posthumous show of Wong’s works on paper, exhibited in Athens at ARCH (organized in collaboration with the Matthew Wong Foundation and Karma). Art historian Winnie Wong’s catalogue essay in Postcards and Todd Bradway’s recent piece in COCOA have recently expanded the critical lens, contextualizing Wong’s work within his biography with greater detail, and assessing the layered motifs of landscape and isolation that thread his output. Before this, in their writing on Wong’s practice (particularly in the expected surge after his death), art critics and journalists leaned heavily on European modernist references. Gustav Klimt, Henri Matisse, Edvard Munch, Vincent van Gogh, and Édouard Vuillard are often mentioned in the same breath as Wong, as well as mid- and late-twentieth-century painters such as Alex Katz, Yayoi Kusama, David Hockney, and Wayne Thiebaud. These names work to underscore Wong’s catholic taste in culture while propping him up. However, not enough attention has been paid to how these distinct references relate to one another, or how Wong is committing his spatial composition to the invocation of a desire for belonging. And there are yet more referents, both historical and contemporary, that inform this aspect of his work.

Wong was a prolific painter who refined his style considerably over the course of his brief career. His early, brightly-colored gardens created with lush brushstrokes, between 2016 and 2018, developed into subdued vistas with a single, faraway figure or empty interiors, rendered in a cooler palette and with tighter application, which Wong explored through to his death. The earlier play of line, color, and brushwork, found in paintings such as Modern Landscape (2017), evokes the bright, undulating style of 1980s David Hockney. However, his later, more circumspect work more closely aligns with the American postwar observational painter Lois Dodd. Her compositional use of windows, doors, and roofs is echoed in Wong’s framing of architectural elements. Flowers brush up against window jambs; trees intersect rooflines. His postmodern assimilation of influences across a wide breadth of history from the late nineteenth-century through the early twenty-first is worth emphasizing because it shows us how the themes Wong addresses, of the constitution of identity and the nature of isolation, remain constant.

Wong’s conjuring of Belle Époque subject matter suitably molded his contemplative study of unexplored regions of the mind. In the mid-1800s, when scientists and philosophers began to explore the creative function of the conscious and unconscious, the aim of the artist pivoted from the reproduction of an exterior object to the treatment of scenes experienced through mood or atmosphere that expressed emotional characteristics. In Symbolist and Expressionist painting, literature, and philosophy, physical space became an expression of personal feeling. The interiority of the mind was illuminated with the description of interior space. Greater emphasis was placed on the subjective states of dreaming and hallucination, as the alienation that many urban inhabitants experienced as a result of the industrial revolution drove a desire for self-reflection. In his famous 1935 essay “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” Walter Benjamin writes, “The interior is not just the universe but also the étui of the private individual. To dwell means to leave traces.” For a group of French artists known as Les Nabis – as well as other painters such as Paul Gauguin, Munch, and Odilon Redon – the domestic interior became a safe place for the mind to function because it was reflected by its surroundings.

Wong’s work follows the logic of Symbolism, projecting aspects of the interior psyche into uncanny, almost phantasmagorical scenes. His landscapes and domestic visions appear filtered through the haze of dream and memory. Elements of the natural world are often sewn into the domestic, framed by a window or nested in corners. In Fireplace, a large oil painting from 2018, a chair faces a fireplace in a wallpapered living room. A window on the left wall gazes out into a moonlit landscape, while a painting of a blurry field bisected by a yellow path is hung on the opposite wall. An orange and white rug beneath the chair bears a pattern resembling tree branches in a forest – perhaps a subtle reference to Wong’s earlier 2018 landscape Somewhere in which a whimsical forest scene is similarly rendered in vibrant orange set against a black ground. These repeating motifs allow Wong to subtly build his own world within the space of his painting.

Wong’s use of the fireplace as a mise en abyme in particular reflects the paradox of his spatial construction. The closer we get to the hearth, the further we are led out into the night. This collapsing of interior and exterior space is reflected in Wong’s painterly style, in which patterns sit on the surface of domestic interiors – a strategy that recalls the bright motifs of French painters Édouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard, both associated with Les Nabis and heavily influenced by Symbolist theory. In particular, Wong’s use of outline to delineate objects within an interior is similar to the clear curving lines Vuillard’s used to distinguish the shapes within his pattern-filled interiors.

Similarly, Wong’s vibrant colors, lyrical, meandering lines, and painterly brushstrokes evoke the dynamic figuration of Expressionist painting. Wong himself cited van Gogh as a major influence in his 2018 interview and directly referenced him in several of his works. A painting titled Starry Night (2019) depicts a sky lit up with small yellow stars encircled by light blue halos, reflected in water rendered in thicker dashes. The undulating shoreline reflects the curve of the mountains and white billows of smoke that recede into the landscape, a bright echo of van Gogh’s dark trees and steeples.

Similarly, promises of warm interiors beckon from distant houses, usually positioned at the end of winding paths carved through the wild terrain. In Blue Rain (2018), a small house sits at the end of a dotted path amidst a field of white flowers and tall birch trees. The large, cool orb of a full moon hangs at the top of the painting, half in frame, while long streaks of rain fall diagonally across the space. A demi-circle of yellow sun with radiating streaks of light peeks out above the green door of the house. Golden light shines through the window. We are drawn toward the structure, which offers elements of both interior and exterior space. The light simultaneously promises the coziness of domesticity and the expansive energy of cheerful weather just out of reach.

In a two-year period that began in 2018 and extended until his death, Wong’s repetition of certain patterns and motifs begin to connect various spaces, both interior and exterior, across his painting. Meanwhile… (2018) depicts a small figure with a tree and a bird inside a vase that holds a single red flower. I wonder if the red flower is the same one that we see in the watercolor January’s Window (2018) and if the figure who is bent over writing next to a flower vase in a red room in The Diary (2017) has been transposed into the flower vase itself. Wong places elements of the inside and outside alongside each other – adjacent, in subtle tension. As viewers, it seems as though we are never entirely located in one space or the other. Nor are we ever exactly where we want to be.

By positioning himself within a lineage of modern and postmodern painters, Wong underscores the persistent nature of questions about desire, loneliness, and the search for larger meaning. His too-short career was marked by the prolific, increasingly virtuosic production of paintings that probed the ways we position ourselves in the world in order to negotiate simultaneous desires for proximity and distance. He is in very good company, asking these contemporary questions while drawing on references from the past. Wong’s early, patterned landscapes such as The Kingdom (2017) are reminiscent of Scottish painter Peter Doig’s figural, dreamlike scenes which paint landscape as memory. The haunting, candy-colored landscapes of Swiss-born painter Nicholas Party share a whimsicality with Wong’s mysterious nightscapes, as well, particularly his use of strong vertical lines of trees juxtaposed with brightly colored moon circles suspended above the foliage.

As Wong gathered the approaches of past and present landscape painters through the traditional media of oil paint and gouache, he marked the continuation of painting’s need to grapple with existential themes and articulated the urgency with which we are still searching. When asked about the melancholic tone of his paintings in his 2018 interview – titled “Matthew Wong Reflects on The Melancholy of Life” – he responded, “I do believe there is an inherent loneliness or melancholy to much of contemporary life, and on a broader level I feel my work speaks to this quality in addition to being a reflection of my thoughts, fascinations, and impulses.” Wong’s treatment of landscapes and interior spaces as a tour of the mind’s inner image crafts a response to the alienation of how we live now – more connected than ever before, and more lonely. In particular, the past year has left so many of us asking where we really want to be, without finding any clear answers about how to get there. At the end of the winding path, Wong’s depictions of the structure of longing help us connect to a truth: that we are not alone in our isolation.