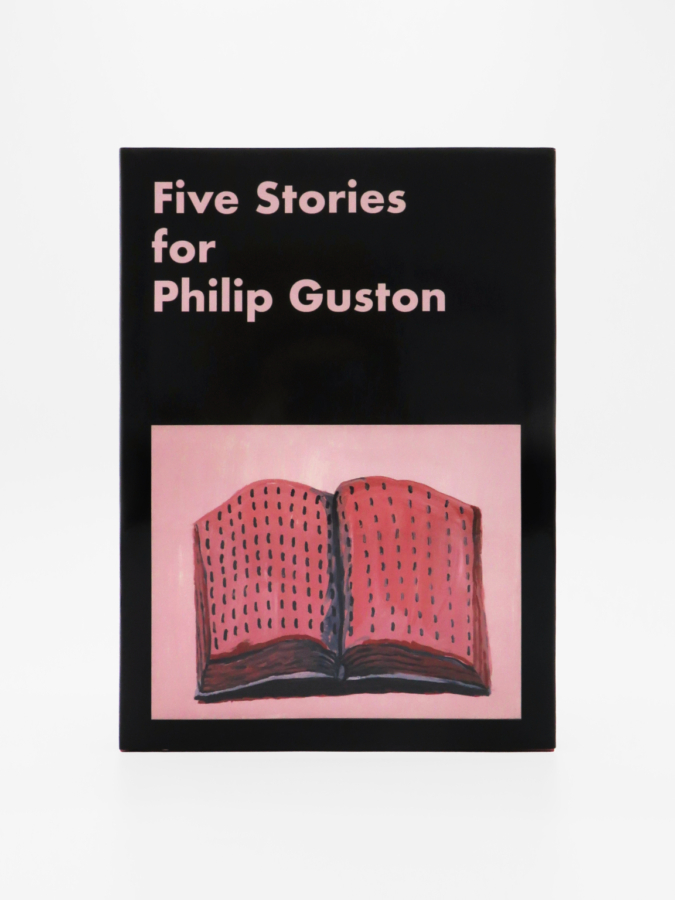

Ann Craven, published by Karma, New York, 2018.

Download as PDF

Ann Craven is available here

Some artists have happy hands. You can see it in the work. This happiness stems from a sense of purpose—we all want to have a sense of purpose—but more important, a happy outcome on the canvas depends on the artist having the right relationship to her purpose – neither too close nor too far away. Some artists use their “purpose” like a hammer with which to hit their own work. A happier approach is to let one’s purpose, or intention, guide the work in a more sympathetic way, like the way you consult a nautical map while piloting a small boat, aware but not too aware of the shore. When an artist achieves that state, each brush stroke contributes to a transmission of energy, from painter to paint, that makes a canvas come to life. And yet, this energy must not be over-determined. (Nobody likes an over-eager painting. Don’t take too many vitamins.) The paint just lands; it’s not trying to prove, or be, anything other than itself. And it is just this self-sufficiency that deter-mines a pictorial world we can believe in. This believability, or the suspension of disbelief, has little to do with the what of the painting, but has everything to do with the how.

And yes, Ann Craven does have happy hands, and happy hands are also spontaneous hands. Of course, what may appear casual is the result of so much practice that it melts away, leaving intention and awareness in its place. But an artist is not a zen monk; even if the result of a prayer-like practice, paintings are being made, not merely puffy clouds of thought. The real news here is that Craven also has a refined pictorial intelligence—the instinct to apply her talent to particular, sometimes provocative, compositional choices. Such as: how about let-ting the beech tree fill the canvas; how about birds silhouetted against a pink gelatinous mass; how about black on black, or red on red?

Ann Craven makes paintings in New York City and Cushing, Maine. Both places give her something to look at. Let’s assume she can paint anything she wants—any soup can—but there is something auspicious in her choices. Moons, birds, friends, and flowers are the perfect runway for her brush. (They allow her to take off.) Painting nature, in all its fullness and momentariness, is to perpetually fail to capture time’s passage, and having to settle for the frozen moment. Like a Japanese master calligrapher, Craven brings her beginner’s mind to these fleeting moments, and discovers something not noticed before—a half-moon bisected by a tree branch, or, from a slightly different spot in the yard, the same moon, now magenta, just before it dissolves into the purple beech. Craven is so much merged with the making of her making, it allows her to reach deeply into painting’s mysterious relationship to time—how to return over and over to the same motif and make it fresh, thereby connecting that frozen moment to the endless accumulation of similar moments, to the whole temporal flow of life.

This returning means that Craven works in series, repeating a motif or pictorial structure, carrying over much from one painting to another. However, each canvas retains its own personality. There’s nothing perfunctory, rote, or gratuitous in a Craven painting. The formal elements have a way of disappearing into a sense of wholeness, rightness, and surprise. In case you didn’t know, this is much harder than it looks, especially the surprise part.

In interviews, Craven says she’s interested in how paint can keep memory alive. The moon is her perfect subject because, in her words, “it appears to change yet it stays the same. It comes back in a repeated cycle, and it’s a repository of memory.” Her paintings can be collages of observed, copied, or appropriated material, and often she intention-ally copies herself. Craven has deliberately made so many renderings of the same subject, and then made more renderings of those renderings, that the mind can go a little numb contemplating them all. Some commentators have objected to this repetitiveness in Craven’s work, as if the intense focus on a limited number of images is a liability. It seems a little churlish to me; no-one scolds certain male artists for making, over decades, stacks of wood or bricks, or words. As a child, you probably wanted to paint houses, little racecars, or big jellyfish, over and over. If you had, probably no-one bothered to tell you to be more original.

Craven has a lot to say about her work, and let’s assume that it’s all true, but what I find compelling is the aliveness of the paintings themselves, detached from their explanations. She has a fondness for images from certain movies, like Soylent Green, a 1973 post-nature sci-fi film. (“In Soylent Green nature was losing, and in my paintings nature is winning.”) True enough, and interesting, but it almost doesn’t matter what an artist’s starting point is; neither painting from life nor some conceptual idea, per se, is going to get your magic carpet started. Just as a good dreamer knows that everything in her dream is her, we feel that the aliveness of Craven’s canvases is hers to give, made at the end of her brush, whether in the form of a moon behind a tree or a sunflower. It’s this convincing transparency of self, added to the simple, direct way Craven structures her pictures, which give the paintings their timeless feel. Add to this quality the spontaneity of her brushwork, which makes them feel contemporary. Timeless and also contemporary—who doesn’t want that? Why not paint flowers and moons? Craven could have painted children, skyscrapers, or aliens on camping trips, but flowers and moons inspire her. More than anything, these are things that can be painted; it’s the translation of this inspiration into paint that convinces us. As a bonus, the work is not without humor; don’t think that moons, flowers, and birds can’t make you laugh.

Painters have probably been painting moons for as long as they’ve been able to look up, but Craven has arrived in her own spaceship. Astronaut with brush, willing to walk funny. Translucent bones, squashed hats, goofy yellow string beans, etheric banana peels, butter thumbprints, fluorescent slits in the night—in all of these ways and more, Craven’s moons convey their moon-ness. Her moon paintings are of modest size; there’s something humble about her use of scale, and possibly her subject too—she’s a moon minimalist. Yet there’s something wild and brave about her fast paint. Will this pink disk, made in a single stroke, say what I mean? How little does it take to make something essential and true? Silky black blocks of sky, streaky moon shadows, predictive weather halos, barely visible pink cloud wisps, or denser flocks of clouds amp up the moon’s narrative possibilities. In paintings, as elsewhere, context is the real storyteller. Go, Ann, be our moon journaler, discovering, moon by moon, just what a moon looks like.

Craven’s moon paintings tend to be mostly in oil, while her flower paintings favor the spontaneity of watercolor, that most difficult of mediums, and Craven is one of the most deft and accomplished water-colorists working today. Her subject, in this medium, tends to be close-ups of flowers. Flower faces. Flowers, one starts to imagine, whom one would meet and not forget. The flowers are presented up close and personal, and the unrepeatable, and partly uncontrollable, nature of the watercolor bleed—violet into yellow, or black into red, gives these flower faces undeniable personalities. There are the talkers and the listeners. The puffed-up and the grumpy. Some appear to float nonchalantly on their stalks, some are what we’d call more grounded. It’s the paint that makes it so. Craven uses a classic approach to watercolor that actively employs the white paper to define contour and shape. Watercolor is a gambler’s medium, though Craven makes it look easy, as if someone slipped her the numbers ahead of time. The paper must know it’s her. Craven has the presence of mind and the control to preserve the bits of white between two petals, say, or other slivers of negative space as they help to define the form.

Craven’s oil paintings of flowers are less ethereal, more about form satisfyingly carved, wet into wet, from Craven’s color garden. There are near monochromatic studies, in particular pink plunges, what it might feel like to climb into a sensory deprivation tank with a single color. There are roses on black grounds as sensuous as the corner of a Manet. Is the work decorative? Is running the 100-meter dash exercise? Craven’s paintings have a strong sense of style, which is not in any way shallow. Style is an energy that sticks around, after fashion evaporates with the next generation.

A whole subset of Craven’s work is comprised of the palettes used to make her paintings. A canvas palette, roughly 24 × 18 inches, typically has blobs of mixed colors in close proximity—sometimes one color takes over the whole surface, other times measured ovals of color hug one edge—and the whole is often topped with a line drawing made with a brush: an owl, a bird, a moon. These inventories of the colors Craven mixed for her painting are like an artist’s log. They are repurposed paintings, yet even Craven’s accidents are pictorial news. Some of these smallish paintings have a bold, close-up scale, and a gestural movement through the paint that is surprising and playful, loose building blocks of tones and gestures. The “palette paintings,” especially the ones with over-drawing, call to mind certain names central to the development of painting over the last fifty years: Twombly, Joan Mitchell, Baselitz, Per Kirkeby, even Schnabel all hover over or pass through them. In the best of the “palette paintings,” something about the relationship of blobby understructure and breezily drawn overlay looks like how we think, the layering and juxtaposing of our different modes of storytelling. It’s as if we draw our daydreams on German Expressionist atmospheres. While Craven claims to feel vulnerable about showing the “palette paintings,” perhaps because they’re personal; it’s not the behind-the-sceneness that’s of interest, but rather getting to see Craven’s consciousness romp around in different costumes—the freedom of her brush in a wig, so to speak. The gorgeous colors are just themselves, without the need to represent, or even take shape. Blobs are the new faces. Id parties for all.

Craven also paints stripes, and the stripes are her blobs on another day. They have an “I know, I’ll paint stripes” factor, as in “I’ll do whatever the hell I want,” which makes you wonder why more painters don’t take this attitude. The willfulness pays off. Typically these stripe paintings are very long, narrow rectangles with wideish bands of color brushed on diagonally, free-hand. The sequences of colors, their placement and juxtapositions have a jazzy, syncopated rhythm, and they give special emphasis to Craven’s love of pink, fuchsia, magenta, and mauve. The stripes seem designed to be shown with other manifestations of her art; they look especially purposeful when shown with Craven’s imagistic paintings—same vibration, different time of day. “Don’t think, just do,” Balanchine famously told his dancers. Craven enviably just does. If she is thinking, then she is consider-ate enough not to weigh us down with it. (Wall text optional.) In fact, dance is not a bad metaphor for these light, quick steps. There’s some-thing humble in Craven’s approach, like building on a small footprint. She will not bonk us on the head with her great painting, though her paintings happen to be great. Craven has compared the act of paint-ing the same subject over and over to the act of praying. It’s as if these prayers show us how to do less and feel more. It feels great.

In her oil paintings, Craven keeps her surface fully descriptive and concise at the same time. When painting wet-into-wet, there is very little going back in—one has to commit. For example, in the painting, Sunflowers (Cushing), four flowers in a glass jar, seen on a green lawn. The jar is described in less than ten brush-strokes, white, grey, and black. The flower faces, yellow, orange, and crimson, all have concave petals rendered in single brush strokes; they are immediate, sympathetic, and unpretentious.

Published by Karma Books, New York

Edition of 1,000

Special edition of 100