Online Viewing Room

May 8–May 15, 2020

Preview May 6–7, 2020

Frieze New York

Online Viewing Room

May 8–May 15, 2020

Preview May 6–7, 2020

Karma is pleased to participate in Frieze New York Online with a selection of works from Gertrude Abercrombie, Henni Alftan, Dike Blair, Will Boone, Andrew Cranston, Ann Craven, Alex Da Corte, Louise Fishman, Marley Freeman, Ruth Ige, Lee Lozano, Paul Mogensen, Thaddeus Mosley, Woody De Othello, Maja Ruznic, Kathleen Ryan, Mungo Thomson, and Andy Warhol

Karma is pleased to participate in the Frieze Chicago Tribute Viewing Room with a solo presentation by Gertrude Abercrombie.

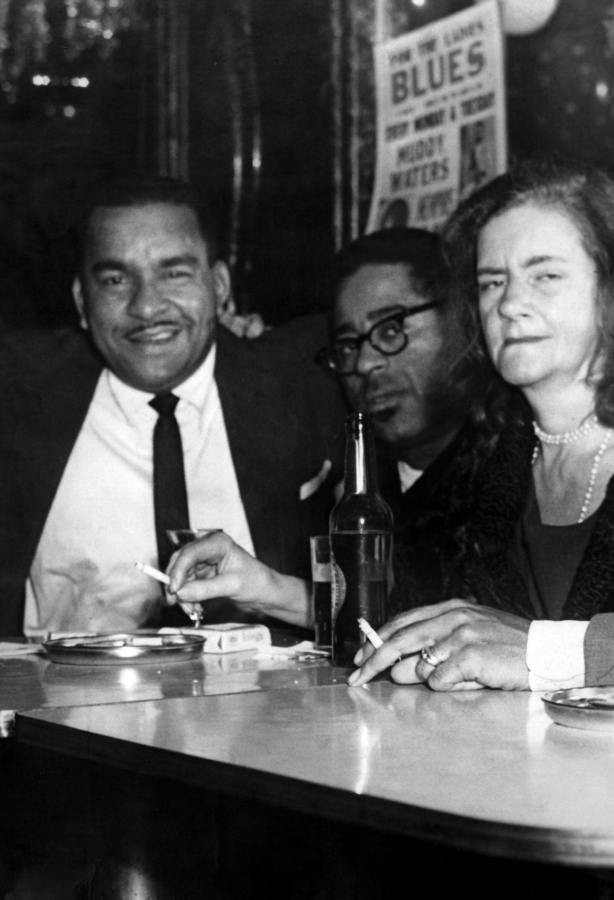

Gertrude Abercrombie exhibited in several Art Institute Annuals and galleries in Chicago in the 1940s and 50s and became the center of several overlapping circles of Chicago and midwestern culture. As Susan Weininger notes, “She hosted a Chicago Salon including jazz musicians, writers, and artists; the liquor flowed freely and she presided imperiously as the self-appointed ‘Queen of Chicago.’” This salon, hosted in her spacious home on Dorchester Avenue, was remarkably progressive and was a safe haven for black musicians who needed a place to stay, practice, or just rest. Many, including Dizzy Gillespie, formed life-long relationships with the artist, who in turn referred to herself as a “Bop” artist. Gillespie later wrote: “Gertrude Abercrombie…has taken the essence of our music and transported it into another form.”

Chicago Tribute is an homage to the pioneering women artists of Chicago, commemorating the 100th anniversary of the ratification of women’s right to vote. The Tribute is curated by Julie Rodrigues Widholm (Director and Chief Curator, DePaul Art Museum), who was recently named ‘Chicagoan of the Year’ by the Chicago Tribune.

Frank Sandiford, Oliver Merriam, Gertrude Abercrombie, Chicago, 1952

Gertrude Abercrombie and her daughter Dinah Livingston, Hyde Park, Chicago, c. 1950s

Frank Sandiford, Dizzy Gillespie, and Gertrude Abercrombie at an outdoor art exhibition, 1956.

Frank Sandiford, McKie Fitzhugh, Dizzy Gillespie, Gertrude Abercrombie, Sonny Stitt, McKie’s Disc Jockey Lounge, Chicago, 1961.

For Gertrude, objects contained life, emotion, process. She attempted to hold on to time by crystallizing it in things. Every surface in her house was covered with assorted juxtapositions of antique rarities, mysterious found fragments, mechanical devices long obsolete, or commonplace items encapsulating a treasured moment with a friend; she revered the past and kept its material remains with her. In her paintings, the houses, pieces of furniture and china, and trees and animals are often identifiable symbols, pieces of her life itself, its inhabitants and events.

-Dinah Livingston, “For Gertrude,” 1991

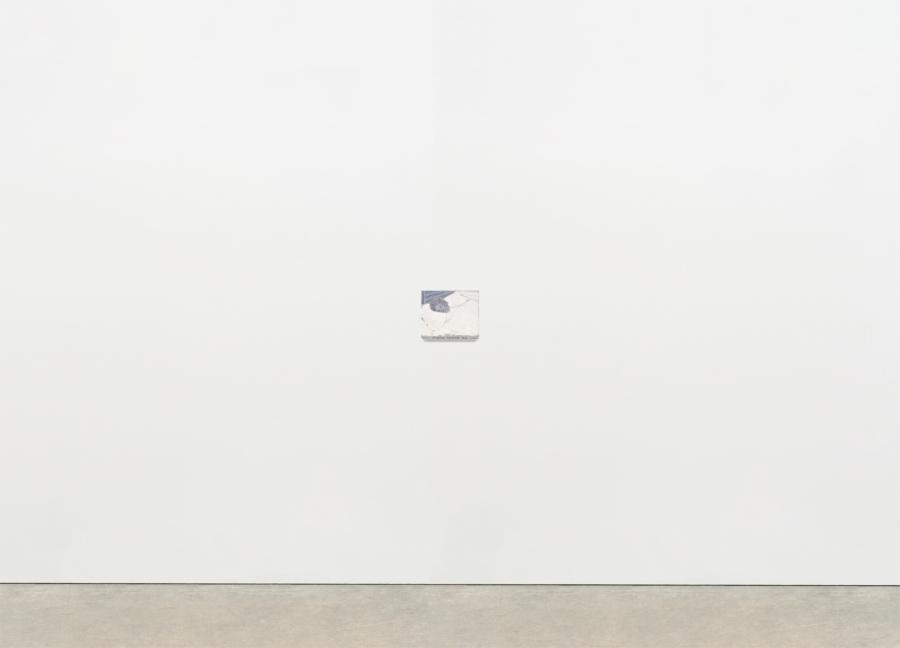

Gertrude Abercrombie

Walls, 1964

Oil on masonite

3 × 3 3⁄4 inches; 7.6 × 9.5 cm

9 × 9 inches; 22.8 × 22.8 cm (framed)

GA-64-003

Gertrude Abercrombie

Walls, 1964

Oil on masonite

3 × 3 3⁄4 inches; 7.6 × 9.5 cm

9 × 9 inches; 22.8 × 22.8 cm (framed)

GA-64-003

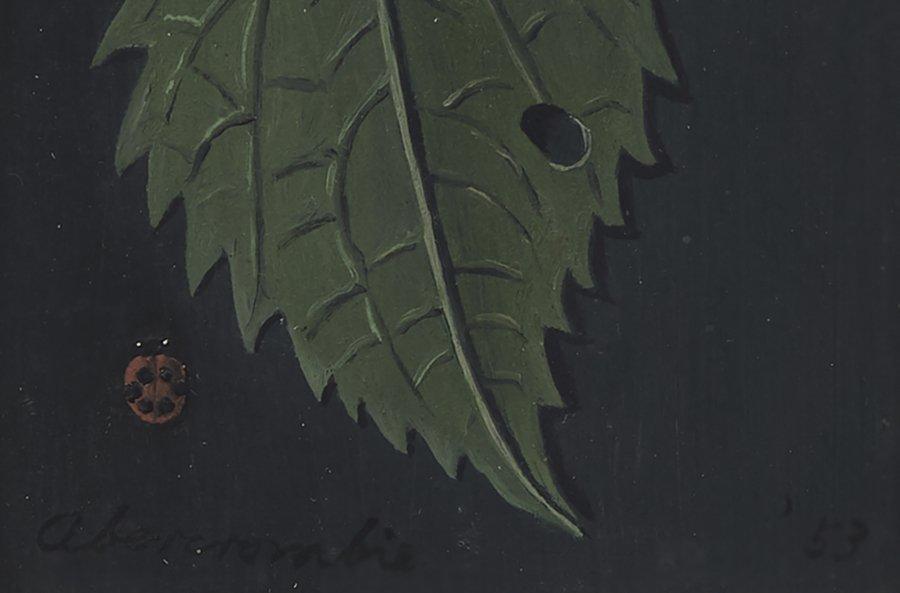

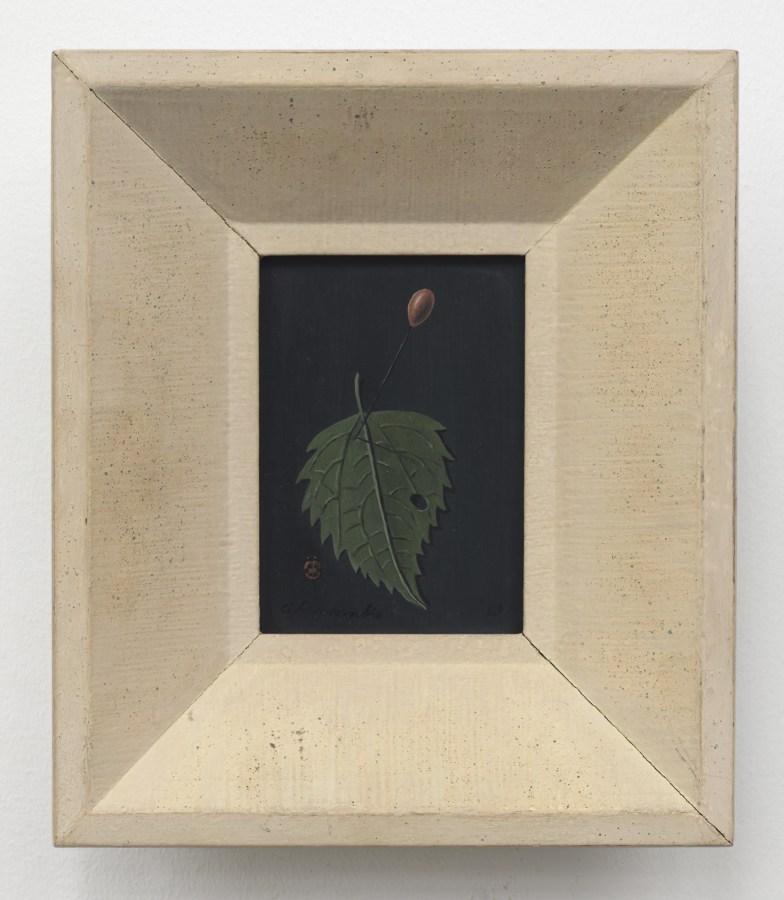

Gertrude Abercrombie

Leaf with Pin and Ladybug, 1953

Oil on masonite

4 1⁄4 × 3 1⁄8 inches; 10.8 × 8 cm

8 1⁄2 × 7 inches; 21.6 × 17.8 cm (framed)

GA-53-002

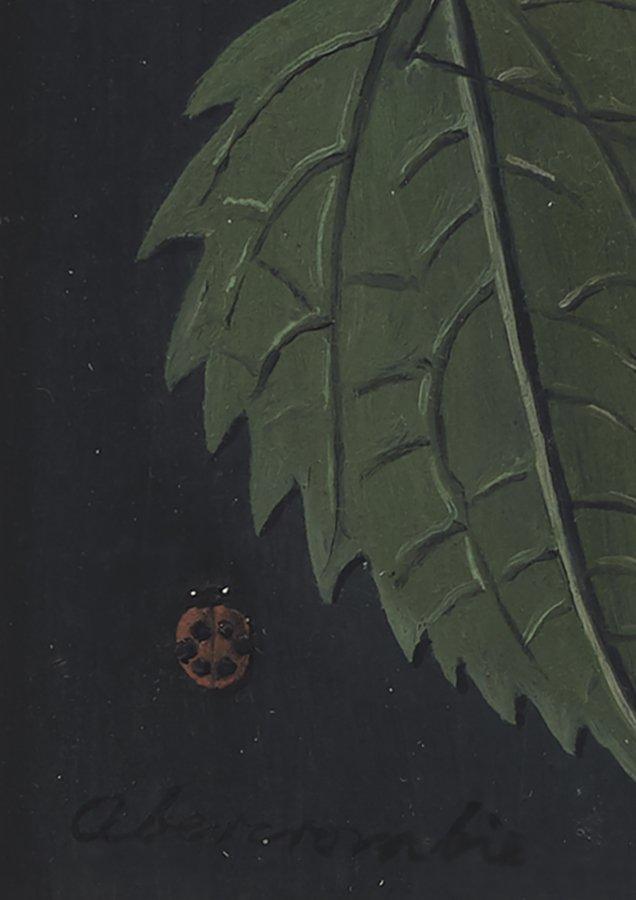

Gertrude Abercrombie

Leaf with Pin and Ladybug, 1953

Oil on masonite

4 1⁄4 × 3 1⁄8 inches; 10.8 × 8 cm

8 1⁄2 × 7 inches; 21.6 × 17.8 cm (framed)

GA-53-002

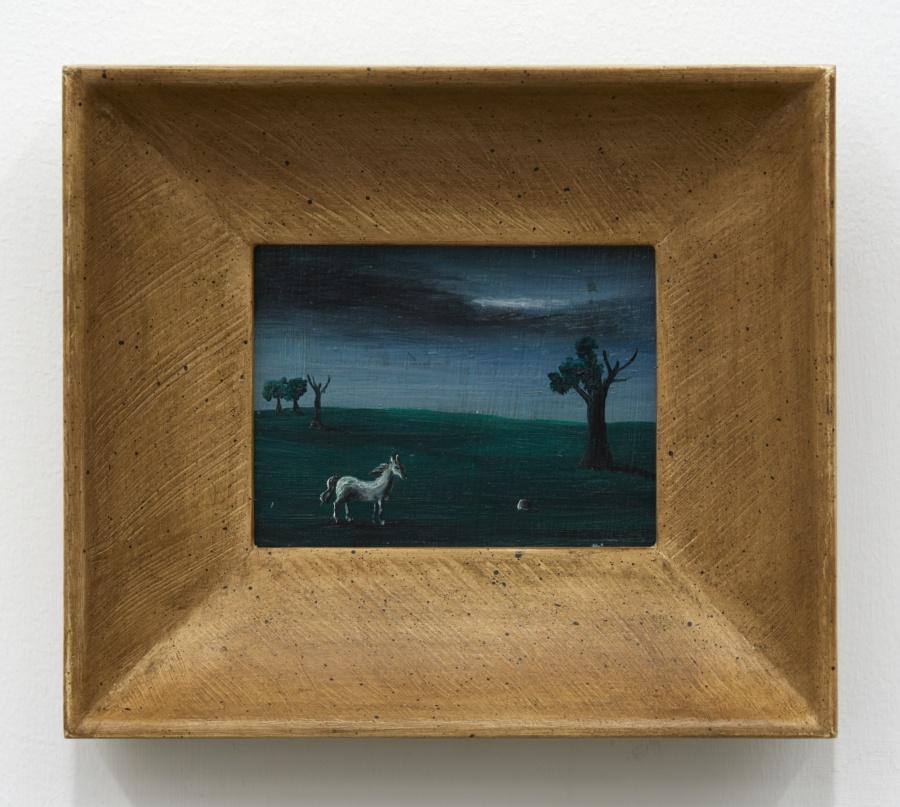

Gertrude Abercrombie

Untitled, 1939

Oil on masonite

3 3⁄8 × 2 1⁄2 inches; 22 × 20 cm

8 5⁄8 × 8 inches; 21.91 × 20.32 cm (framed)

GA-39-005

Gertrude Abercrombie

Untitled, 1939

Oil on masonite

3 3⁄8 × 2 1⁄2 inches; 22 × 20 cm

8 5⁄8 × 8 inches; 21.91 × 20.32 cm (framed)

GA-39-005

HENNI ALFTAN

“She’s grabbing for what he can’t see now, light blocked by depth. A warm day turned cold at its edges. Carefully avoid discussion, deliberate to avoid harm. No hand on deck. Light is absorbed and scatters. The psychology surrounding water. It reduces him. She is veiled, retains her secrecy. She is organized, she has the matter in hand…

The motor waits. Reflection clings like shadow, doubled over the horizon crease, interfering between moments. Time folds, intersects, an imperfect copy, and the parallel fades. What he can’t see is blue, a difference of depth, it exceeds his reach…

What is nearly empty is abundant in part. He knows what this is: causal isolation. Back on land but more at sea. One of a pair—the material one implies the immaterial other. What humans do with their hands. Complete and freestanding, one with reference to no other, what is this but floating?”

-Sarah Blakley-Cartwright, 2019

Henni Alftan

Night Flight, 2019

Oil on canvas

31 7⁄8 × 25 1⁄2 inches; 81 × 65 cm

HA-19-024

Henni Alftan

Night Flight, 2019

Oil on canvas

31 7⁄8 × 25 1⁄2 inches; 81 × 65 cm

HA-19-024

Dike Blair Studio, New York, 2020

DIKE BLAIR

Dike Blair’s most recent body of paintings revolves around the same deceptive sense of scale, ostensibly diminutive yet opening onto another kind of meditative expansiveness. Even the artist himself observes, “I’d assumed their scale would make them feel tiny, but in some ways they’re more dynamic than [my] larger pieces.” This dynamism is also indebted to a telescopic vision that renders the most idiomatic occasions psychological in their isolating focus: a juice box at a Japanese train station; a pint glass set beside the window of an airport bar; a glass of water placed on a countertop before a diner’s table setting; a Negroni set on a Heineken coaster beside a cup of nuts and basket of chips. Significantly, all these scenes could be considered the stuff of still life. But whereas such genre studies might frequently offer allegories of the passage of time, Blair’s subjects more rightly engage the passing of time—or, again, the organization of time, and the social alignments of its cadences. Indeed, so many of his selected subjects revolve around interstitial moments and transitions: the moment after the cigarette has been crushed in the makeshift ashtray; the minutes spent waiting for the next flight or train; the drink received in anticipation of the main dish that will arrive. Blair’s images dial into, and offer entryways onto, the subconscious cues by which one orients oneself.

-Tim Griffin, 2020

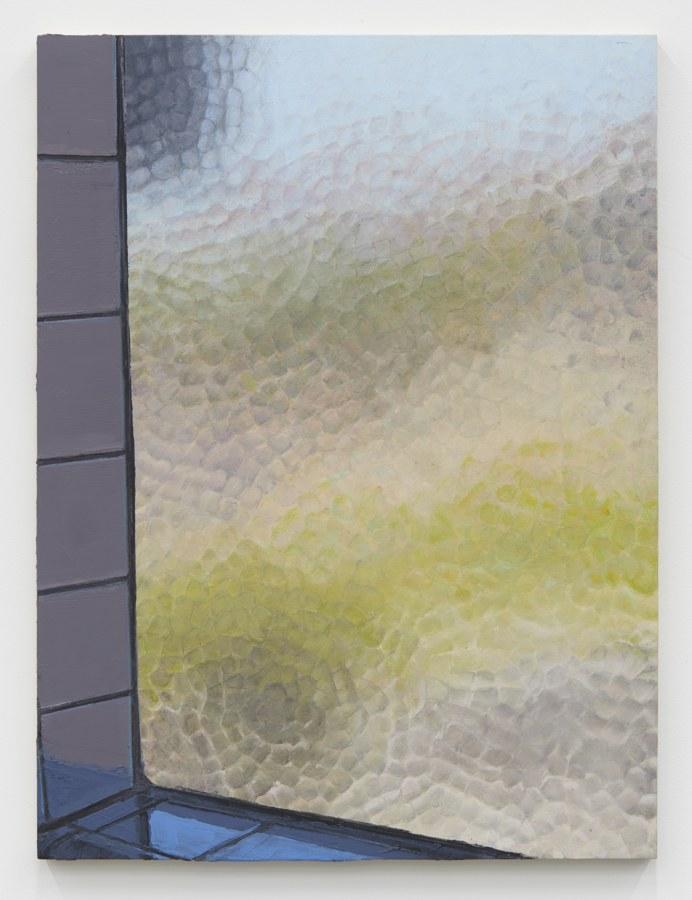

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Oil on aluminum

24 × 18 inches; 61 × 45.7 cm

DB-20-002

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Oil on aluminum

24 × 18 inches; 61 × 45.7 cm

DB-20-002

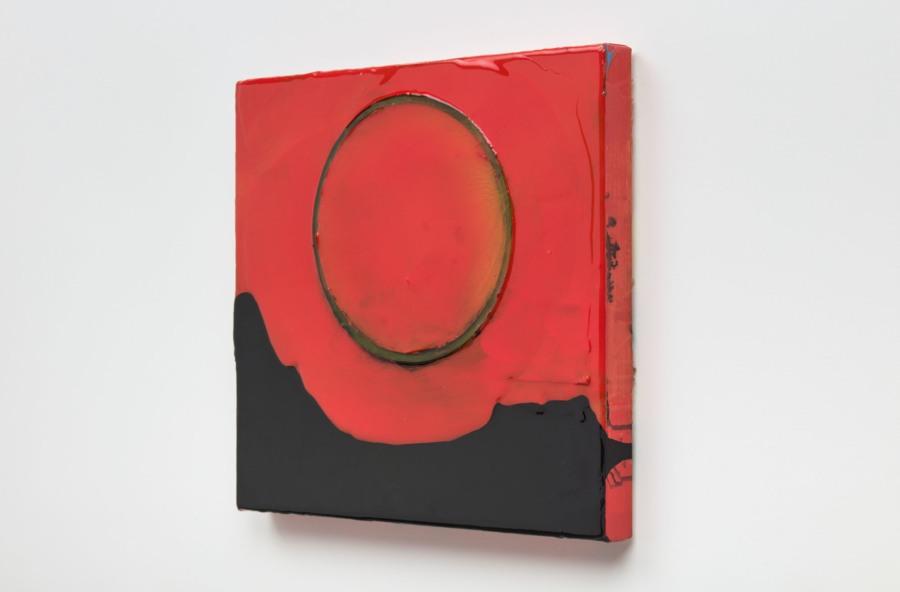

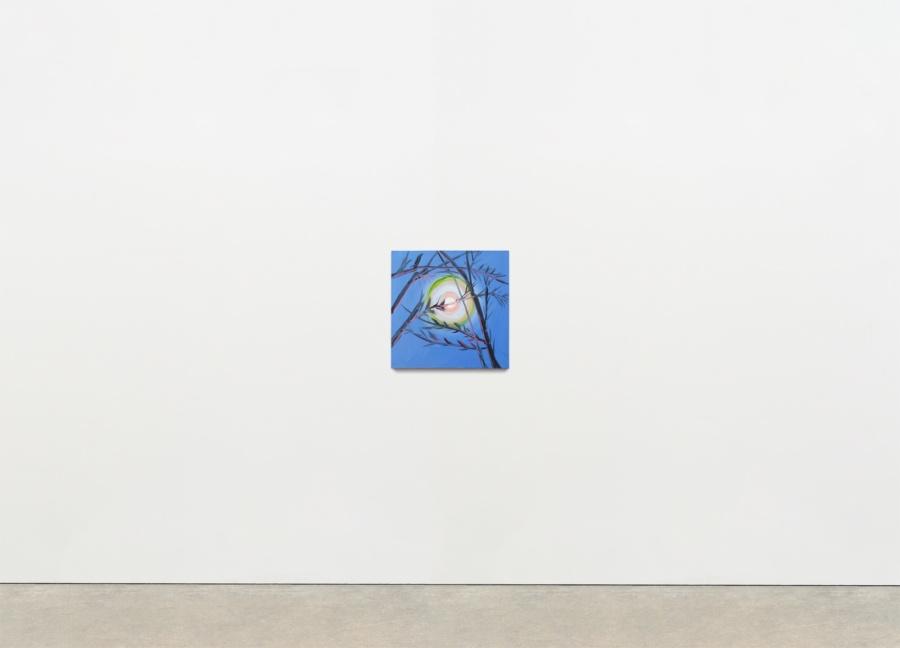

WILL BOONE

“I think my relationship with color comes from my early days making concert posters and shirts. When you add a color to a silkscreen print, it complicates things. There is an urgency or a frenetic energy that is lost when a process is expanded. Silkscreen printing is physical and active, and I believe that some of this energy is transferred into the print, similar to a drawing or painting. If it takes too long and the energy gets lost, it can end up feeling dead. It’s like recording music live in one take versus going track by track and doing each instrument. I’ve carried this into my painting without thinking about it. My choice of color is very specific. I will only use a color after I’ve seen it somewhere—on a car, a sign, or something like that. Normally I don’t have a lot of colors that I use.”

—Will Boone in conversation with Chiara Moioli, Mousse Magazine, 2019

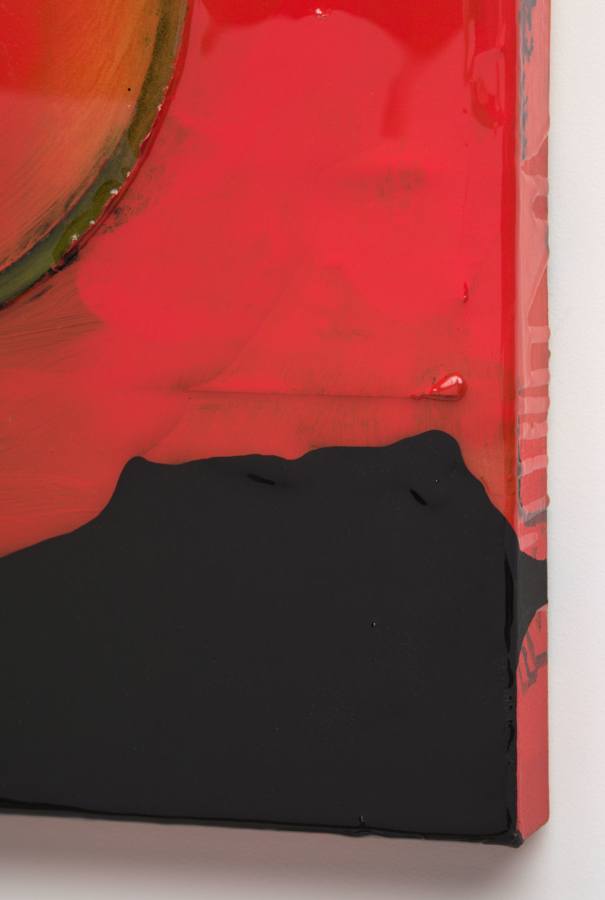

Will Boone

The Super Blood Wolf Moon of 2019, 2019-2020

Acrylic, enamel and resin on canvas

18 × 20 inches; 45.72 × 45.72 cm

WB-20-004

Will Boone

The Super Blood Wolf Moon of 2019, 2019-2020

Acrylic, enamel and resin on canvas

18 × 20 inches; 45.72 × 45.72 cm

WB-20-004

ANDREW CRANSTON

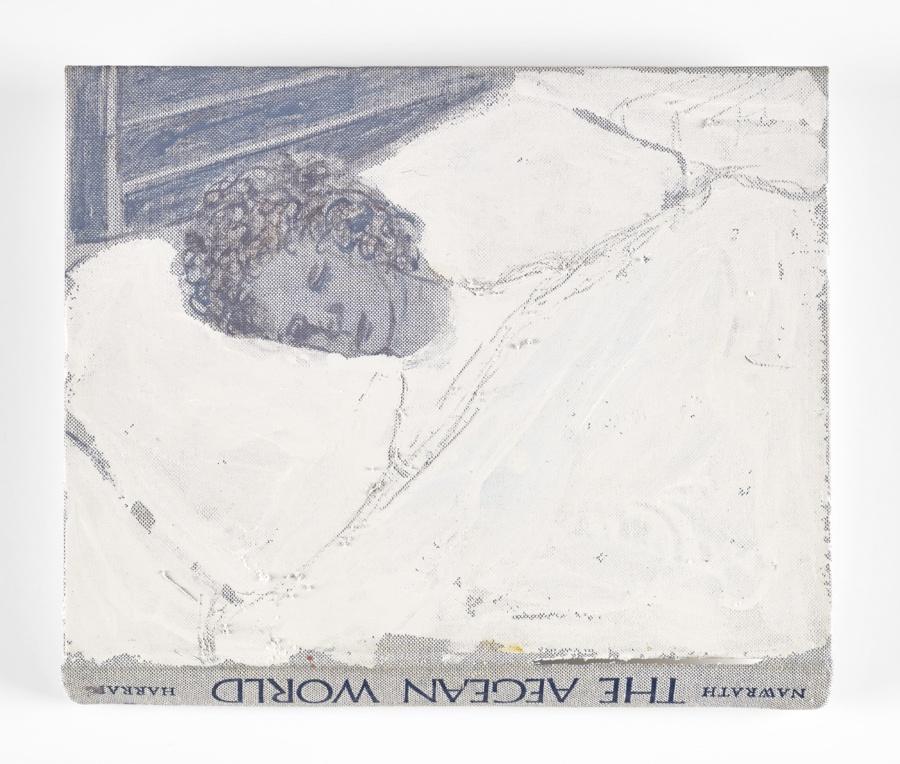

Cranston’s painting style is rich, textural and layered. His oil is either rough and scored, as in the decaying walls around the figure lying prone, etherised perhaps, or smoothed into accumulated layers of thick varnish. The varnish paintings have a cloisonné aspect to them, the painted surface glossy and hardened. The technique allows glimpses into lower layers, with contrasting colours gleaming through to the surface. The end product has the gorgeous, smooth, fused finish of vitreous enamel.

—Claudia Massie, The Spectator, February 17, 2016

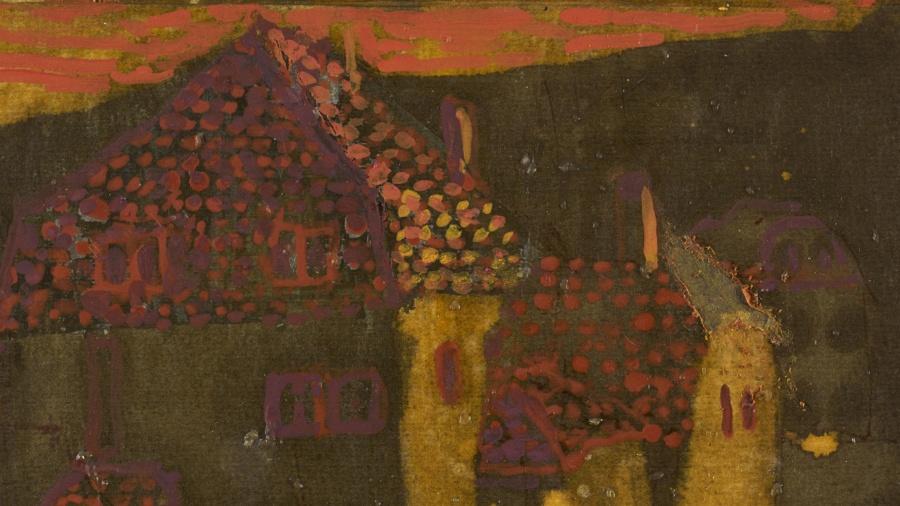

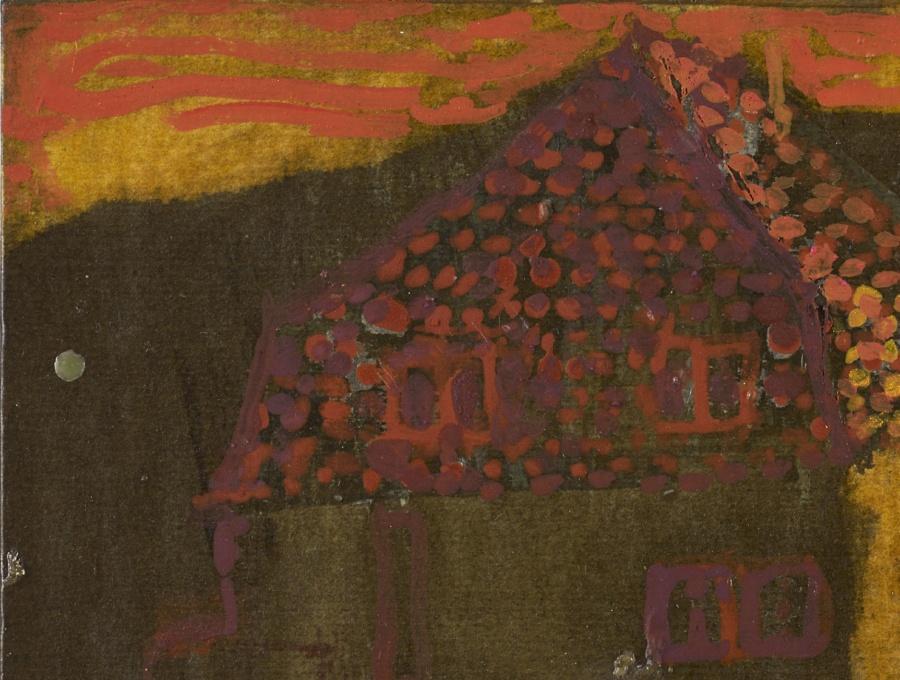

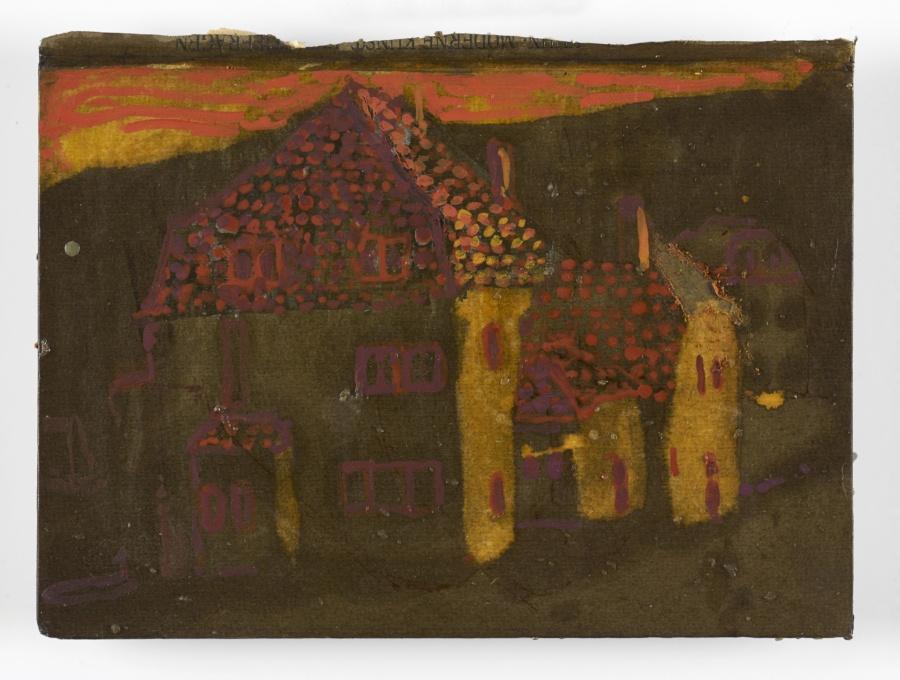

Andrew Cranston

Oberammergau, 2019

Distemper on hardback book cover

8 1⁄2 × 11 5⁄8 inches; 21.7 × 29.4 cm

ACR-19-003

Andrew Cranston

Oberammergau, 2019

Distemper on hardback book cover

8 1⁄2 × 11 5⁄8 inches; 21.7 × 29.4 cm

ACR-19-003

Andrew Cranston

Jason, 2018

Oil and varnish on hardback book cover

10 1⁄8 × 12 1⁄8 inches; 25.5 × 30.5 cm

ACR-18-005

Andrew Cranston

Jason, 2018

Oil and varnish on hardback book cover

10 1⁄8 × 12 1⁄8 inches; 25.5 × 30.5 cm

ACR-18-005

Ann Craven Studio, Cushing, Maine

ANN CRAVEN

For a self-reflexive artist such as Craven the moon is a natural subject; its glow is a memory of sunlight that has already illuminated a faraway place. Like her animals, the moons seem to be assessing us, but unlike her animals there is no threat of obsolescence and she pointedly describes these paintings as a “continuum,” rather than the more finite term “series.”… This sense of university and timelessness was crucial to Craven: “To know that my mother or father looked at the moon many times feels hopeful. The moon becomes a way to connect a memory that fades as time goes on. It allows the memory to retain, and the remembrance continues to become deeper.”

With the certainty of gravity, each night the moon provides opportunities for both surprise and familiarity, making it an ideal subject for Craven’s cyclical way of working. Craven’s lunar paintings demonstrate the infinite variability of the moon’s showings, as well as the infinite possibilities of oil paint in Craven’s hands…every hue is represented, defying any expectations for consistency in the night sky.

-Dana Miller, “Ann Craven: The Nature of Memory,” Karma, New York, 2018

Ann Craven

Moon (Full Lavender Halo, Blue Sky, Cushing, 8-26-18, 11PM), 2018, 2018

Oil on linen

24 × 24 inches; 60.96 × 60.96 cm

AC-18-057

Ann Craven

Moon (Full Lavender Halo, Blue Sky, Cushing, 8-26-18, 11PM), 2018, 2018

Oil on linen

24 × 24 inches; 60.96 × 60.96 cm

AC-18-057

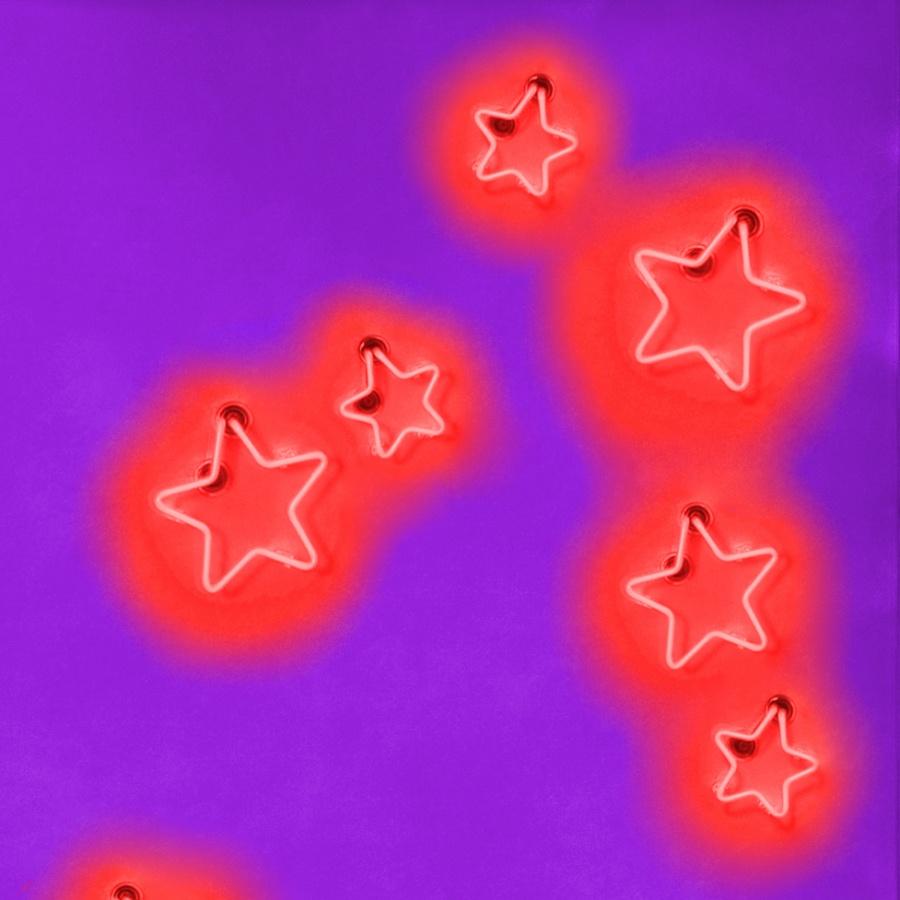

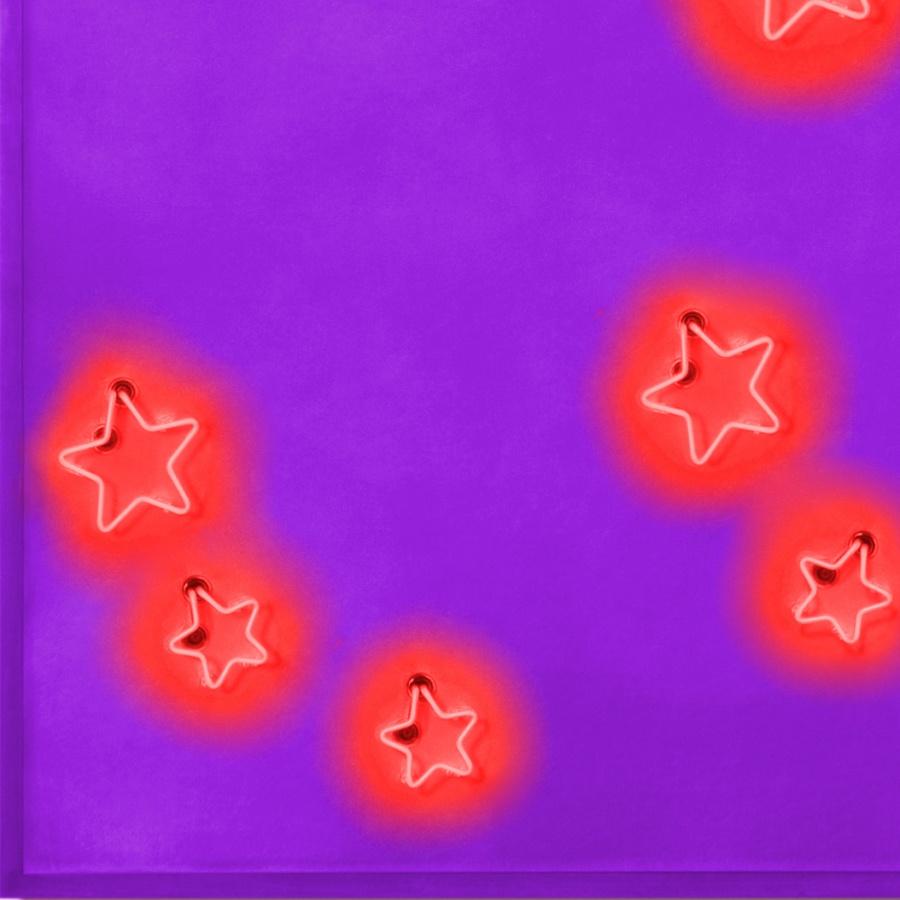

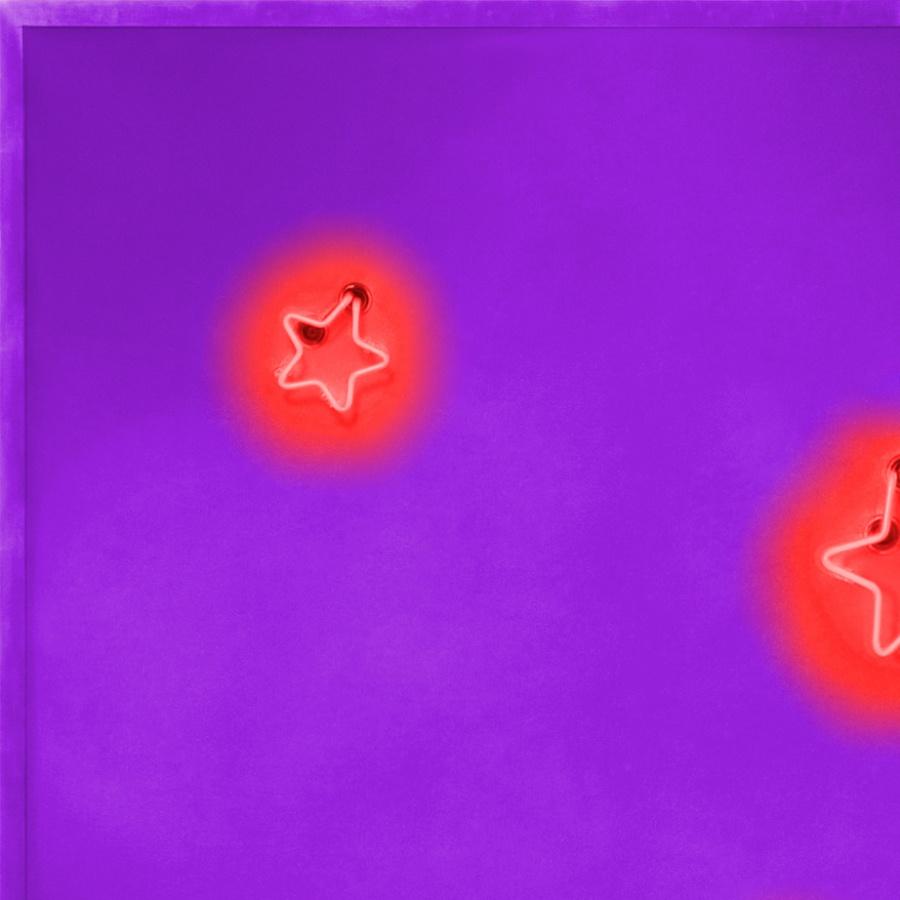

ALEX DA CORTE

Da Corte builds on astrological color theory with Goethe’s 1810 Theory of Colours, which explores the poetics of color through descriptions of phenomena such as refraction and chromatic aberration. The link between celestial observations and terrestrial events, as astrology suggests, also links the individual to the collective. As Goethe writes: ‘In nature we never see anything isolated, but everything in connection with something else which is before it, beside it, under it and over it.’

Alex Da Corte

Sewn To The Sky (Scorpio), 2020

Neon, velvet, hardware, and sequin pins in hard maple frame

73 × 73 × 8 inches; 185.42 × 185.42 × 20.32 cm

ADC-20-021

Alex Da Corte

Sewn To The Sky (Scorpio), 2020

Neon, velvet, hardware, and sequin pins in hard maple frame

73 × 73 × 8 inches; 185.42 × 185.42 × 20.32 cm

ADC-20-021

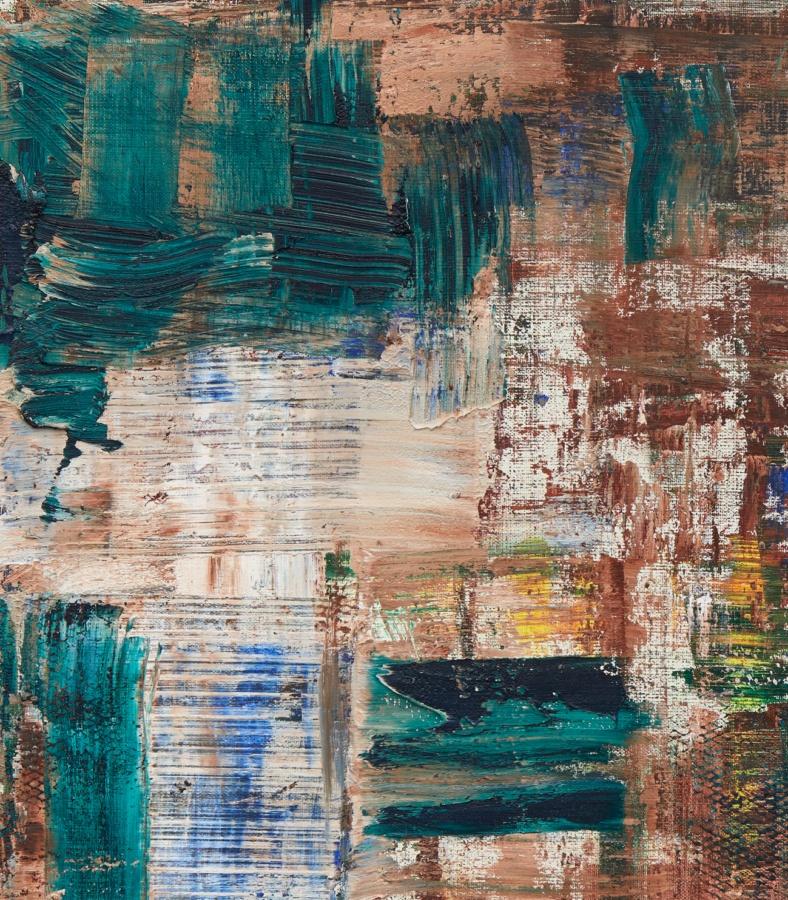

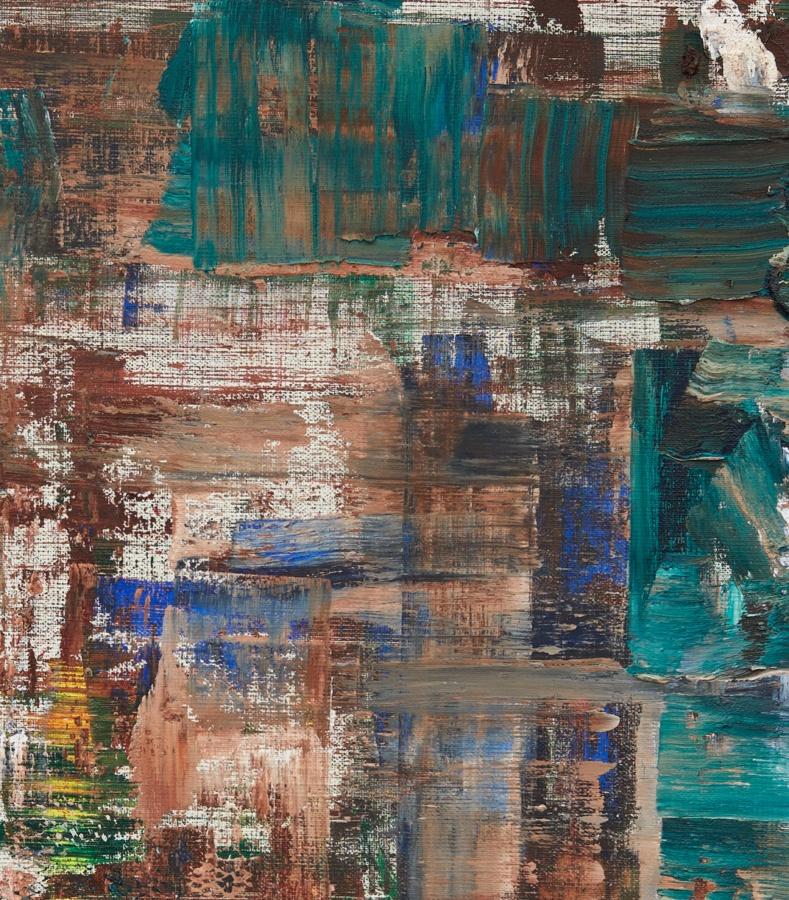

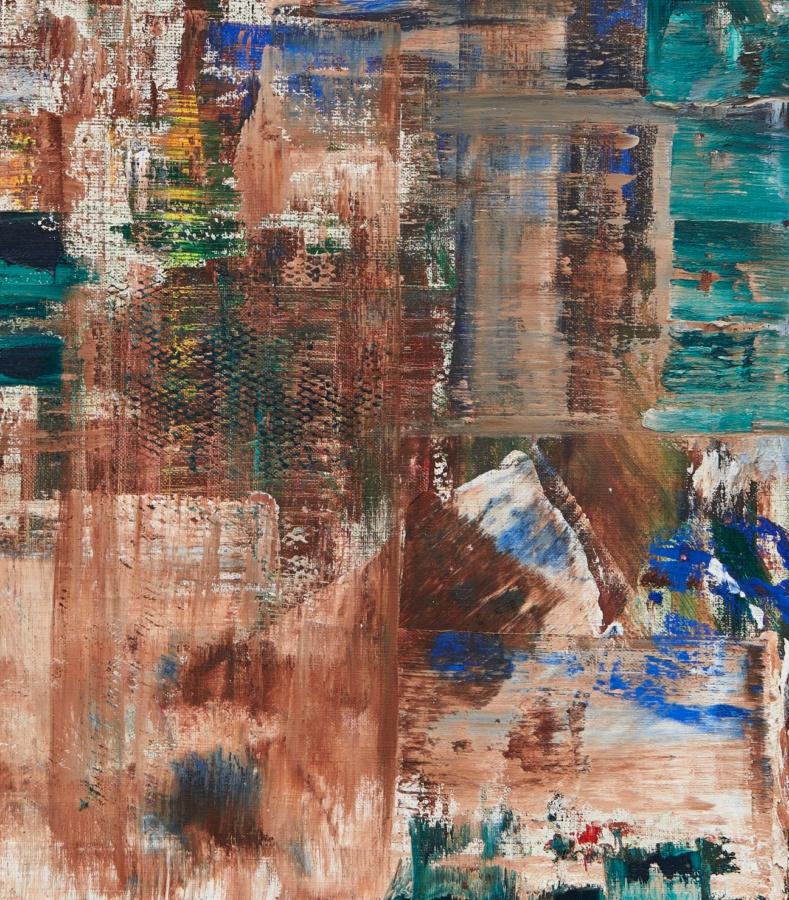

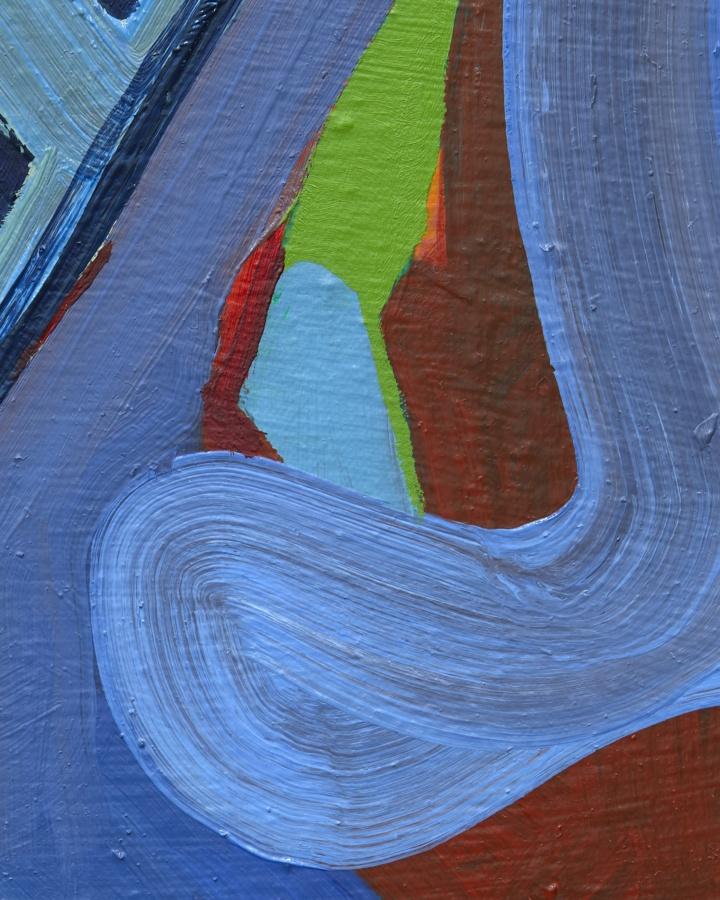

LOUISE FISHMAN

Each of [Louise’s] pigments has a distinctly different coloristic and optical effect depending on how it is applied – whether troweled on thick as plaster by a wide knife, dragged by a scraper across the nubby canvas, diluted and painted in thin washes, squeezed directly from the tube, pressed on using a bit of paper, cardboard and strips of painter’s tape, at times left in place, at others peeled off, leaving an irregular, raised pattern behind (the Surrealists called this technique “decalcomania”), or laid on in one of the myriad other ways that Fishman manages to get paint on canvas. The surface is the site of an endlessly fascinating array of light effects as a result, ranging from transparency to opacity, from matteness to opalescence…This play of color, brushstroke, and luminosity…is counterbalanced by the grid, a constant presence in her oeuvre. Fishman’s grid functions not so much as a predetermined scaffold but as an always emerging specter: she does not start with the grid; it develops through an intuitive process of mark-making. Every time she makes a move, applies a block of color, or scrapes it down again, a matrix surfaces on her canvas; yet when we try to pin it down, to trace its horizontals and verticals, to see it as a form in and of itself, it disappears and all we can see are those marks, the blocks of color, the scrapings.

-Aruna D’Souza, “Doing and Undoing: On Some Recent Paintings by Louise Fishman,” 2017

Louise Fishman

BY THE ELMS, 2019

Oil on linen

40 × 40 inches; 101.6 × 101.6 cm

LF-19-006

Louise Fishman

BY THE ELMS, 2019

Oil on linen

40 × 40 inches; 101.6 × 101.6 cm

LF-19-006

Louise Fishman

Untitled, 2020

Watercolor, color pencil, and pencil on paper

6 × 9 inches; 15.24 × 22.86 cm

9 × 12 inches; 22.86 × 30.48 cm (framed)

LF-20-021

Louise Fishman

Untitled, 2020

Watercolor, color pencil, and pencil on paper

6 × 9 inches; 15.24 × 22.86 cm

9 × 12 inches; 22.86 × 30.48 cm (framed)

LF-20-021

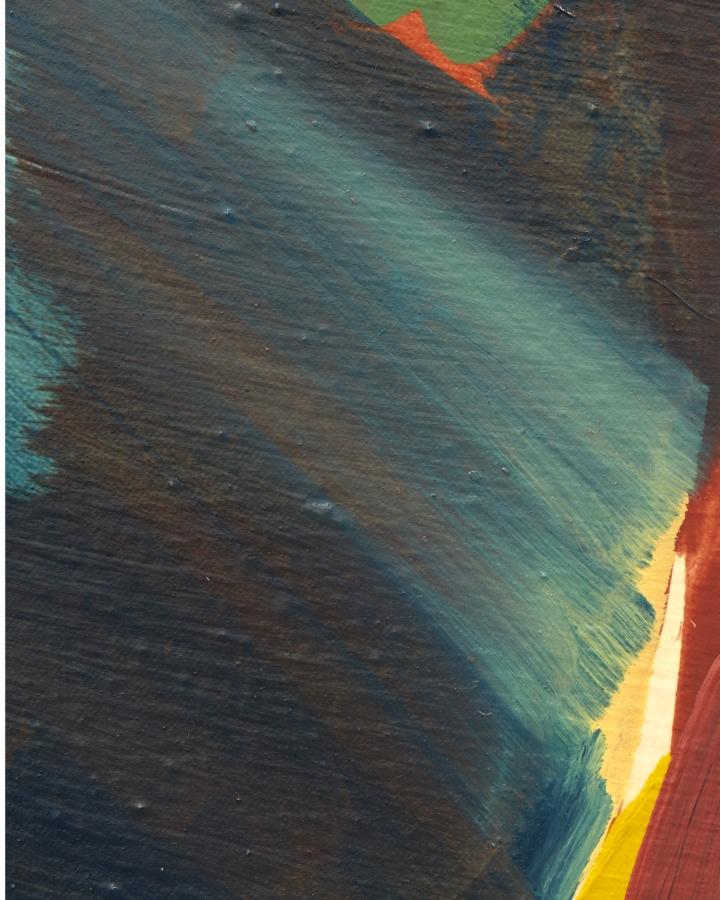

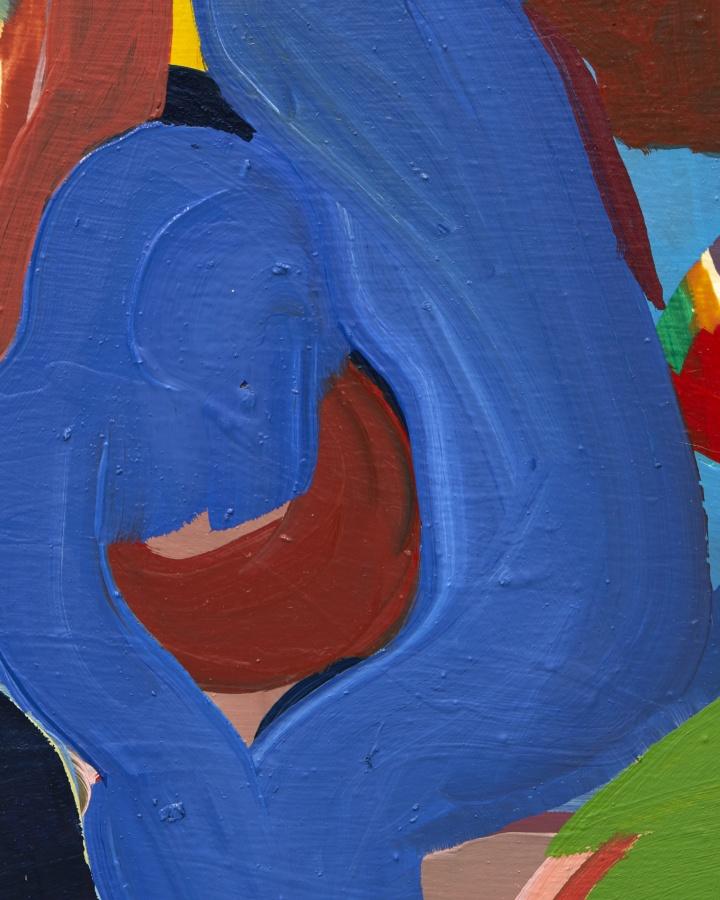

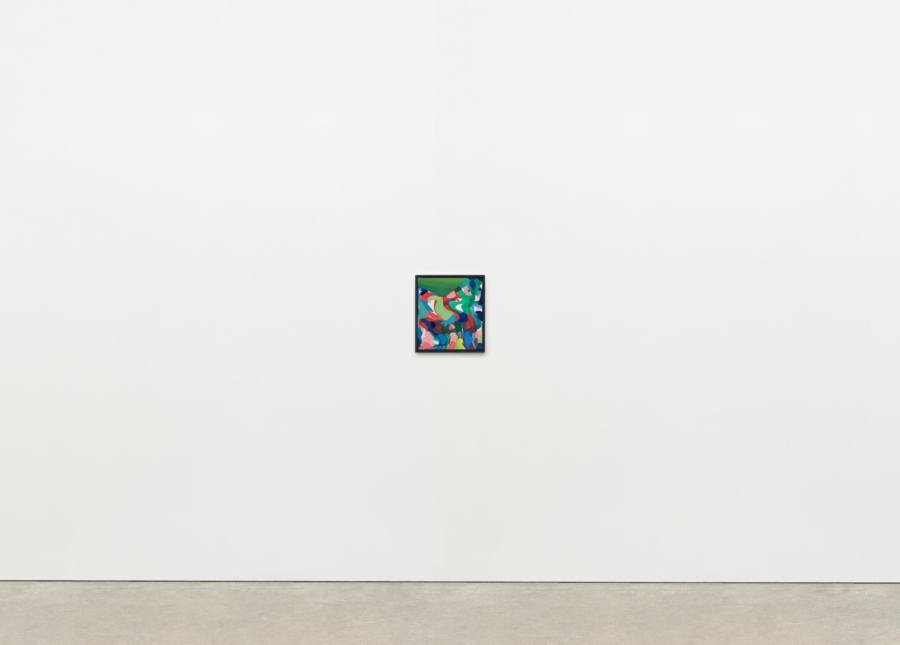

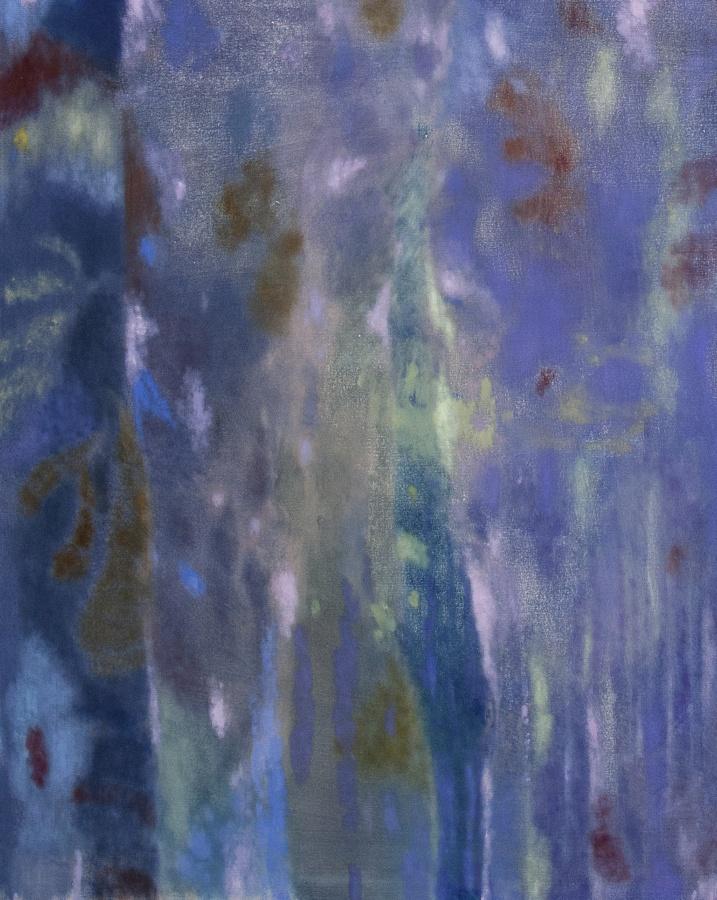

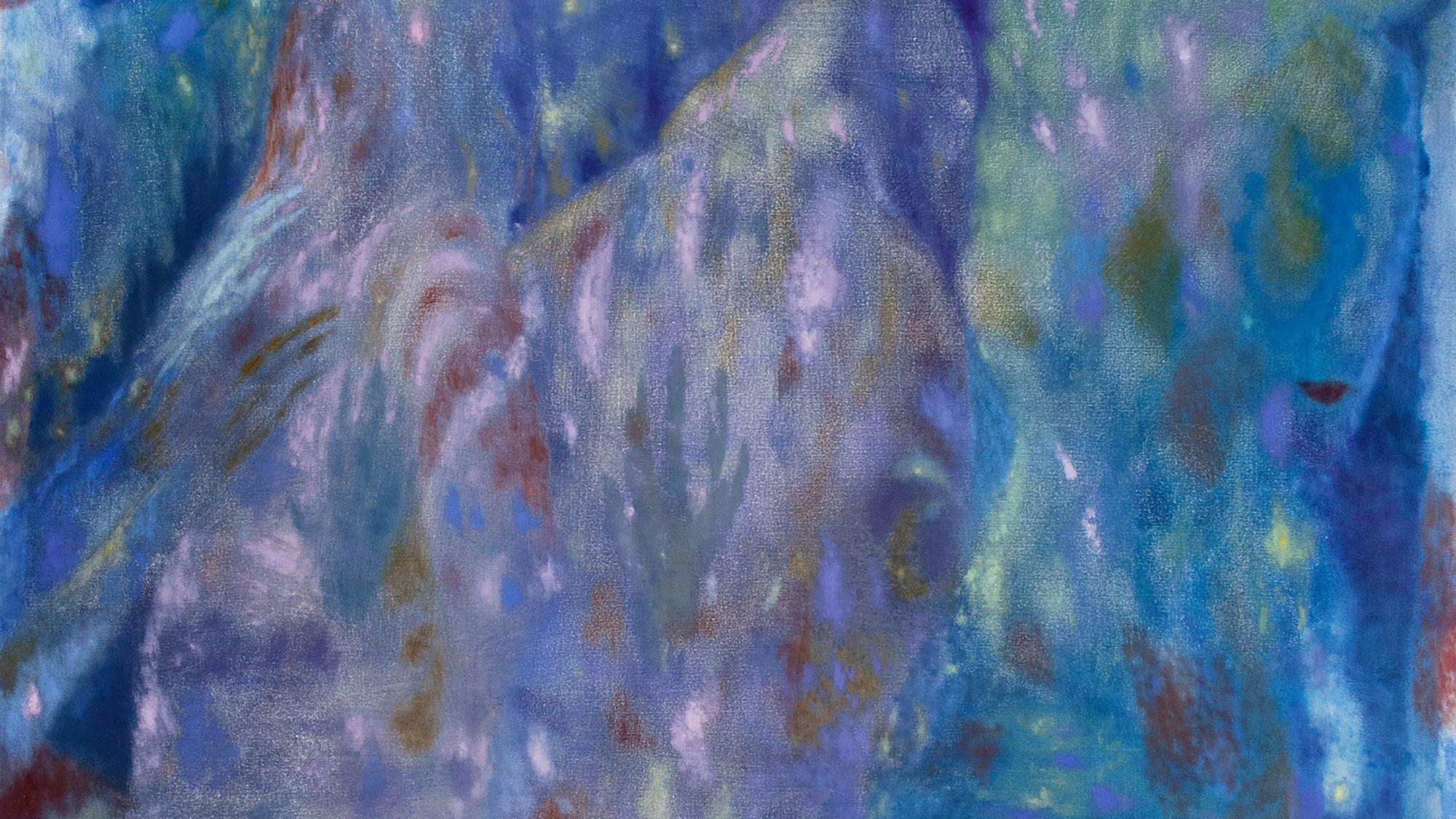

MARLEY FREEMAN

The various layers of paint on each canvas, and the building up of sculptural shapes through veils of hue and luster, create an effect where illumination seems to seep through each work, pushing out from the back, like light flickering through tree branches. Other paintings do the opposite. They pull in the world, absorbing everything around them…teeming with undercoats of paints that, though fixed, still seem fluid and mutable.

-Lauren O’Neil-Butler “Of Equals” Marley Freeman, Karma, 2019

Marley Freeman Studio, 2020, Massachusetts

Marley Freeman

Girls Doing Things Together, 2020

Oil and acrylic on linen

26 × 24 inches; 66 × 61 cm

27 1⁄4 × 25 1⁄4 inches; 69.22 × 64.14 cm (framed)

MF-20-008

Marley Freeman

Girls Doing Things Together, 2020

Oil and acrylic on linen

26 × 24 inches; 66 × 61 cm

27 1⁄4 × 25 1⁄4 inches; 69.22 × 64.14 cm (framed)

MF-20-008

Marley Freeman

Declare, 2020

Oil and acrylic on linen

16 × 18 inches; 40.64 × 45.72 cm

17 1⁄4 × 19 1⁄14 inches; 43.81 × 48.44 cm (framed)

MF-20-034

Marley Freeman

Declare, 2020

Oil and acrylic on linen

16 × 18 inches; 40.64 × 45.72 cm

17 1⁄4 × 19 1⁄14 inches; 43.81 × 48.44 cm (framed)

MF-20-034

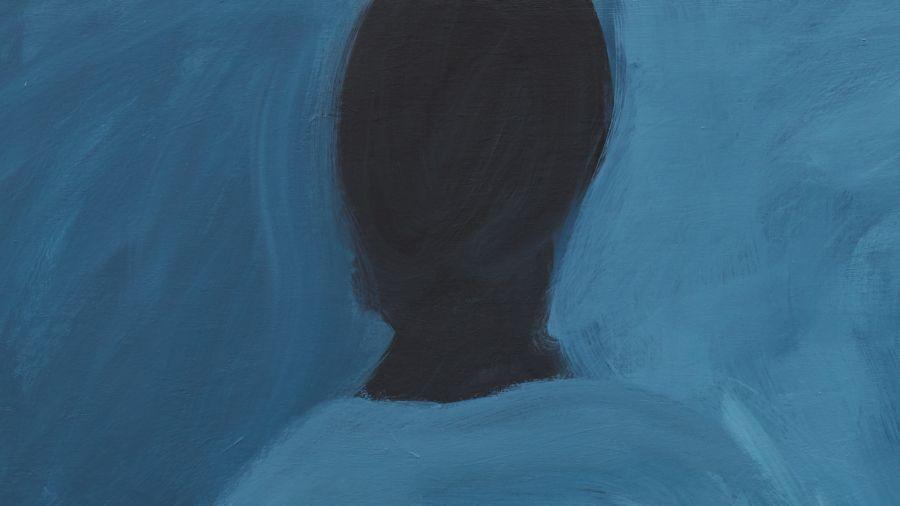

RUTH IGE

[Ruth Ige] uses figuration like a weight to hold down great swoops of acrylic indigo, cerulean and gray. This figurative weight, though head-shaped and solid black, is the opposite of a silhouette. Its blackness isn’t neutral or empty but full and mysterious, a place where gestures and moods concentrate into unknowable density.

-Will Heinrich, New York Times, 2019

Ruth Ige

From the vortex, 2020

Acrylic on canvas

47 1⁄4 × 47 1⁄2 inches; 120.02 × 120.65 cm

RI-20-001

Ruth Ige

From the vortex, 2020

Acrylic on canvas

47 1⁄4 × 47 1⁄2 inches; 120.02 × 120.65 cm

RI-20-001

Hollis Frampton, Lee Lozano, 1963 © Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, © Hollis Frampton

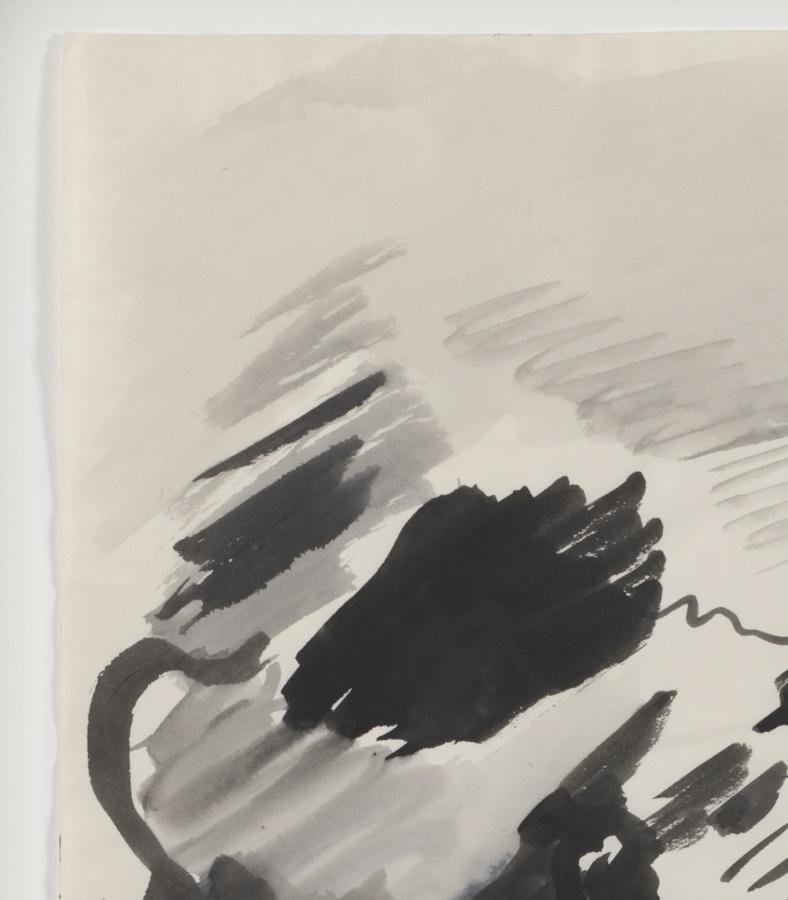

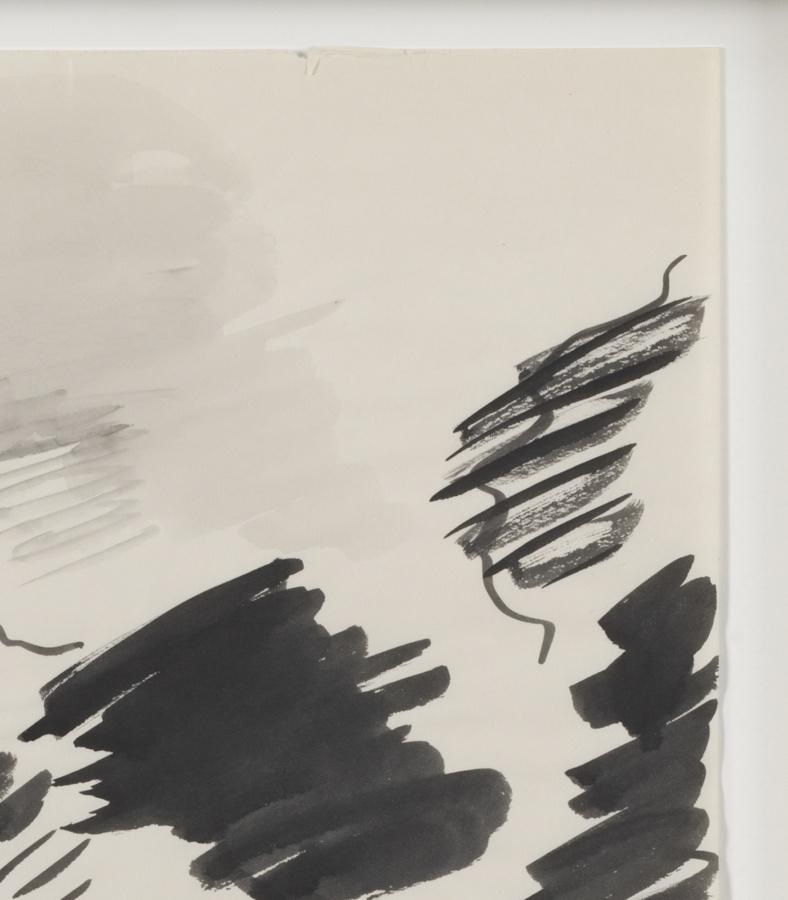

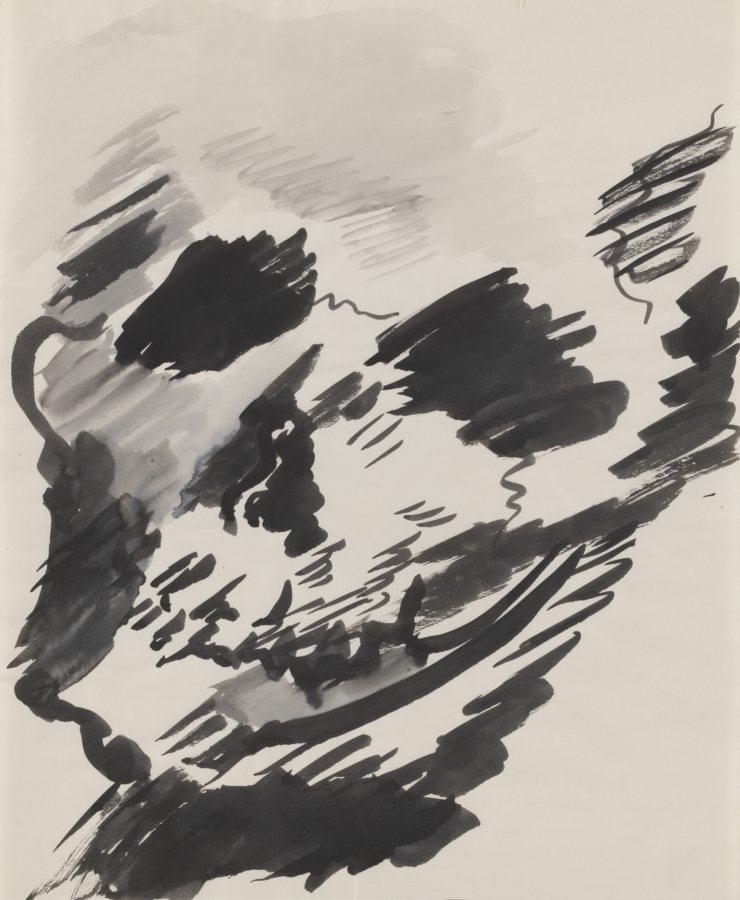

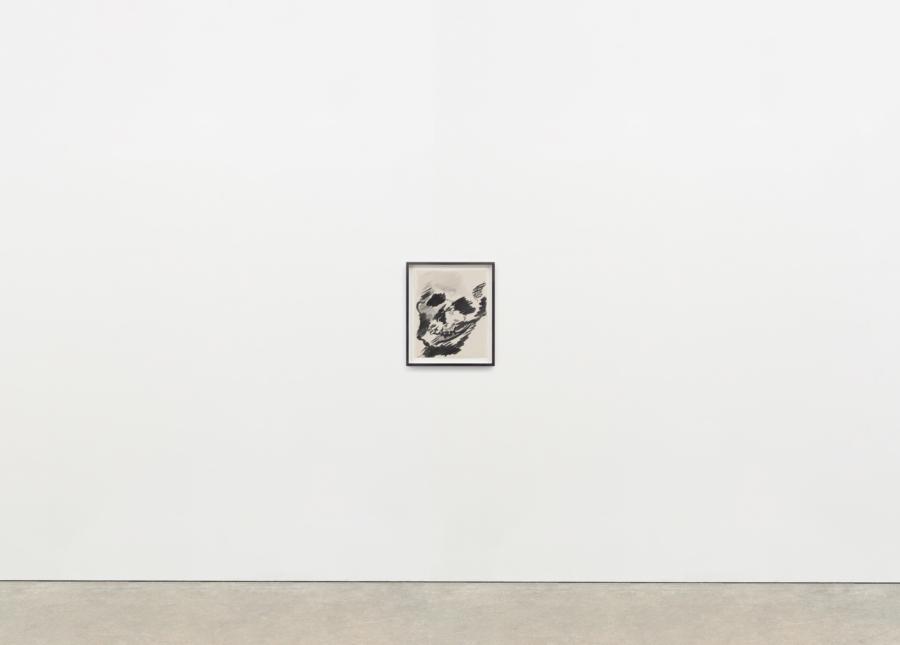

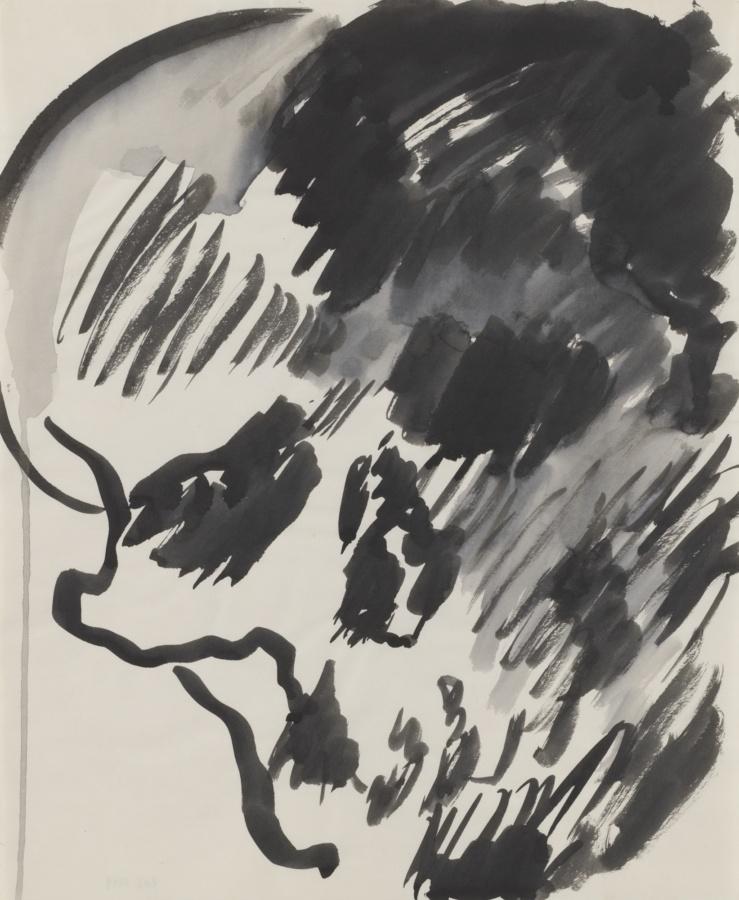

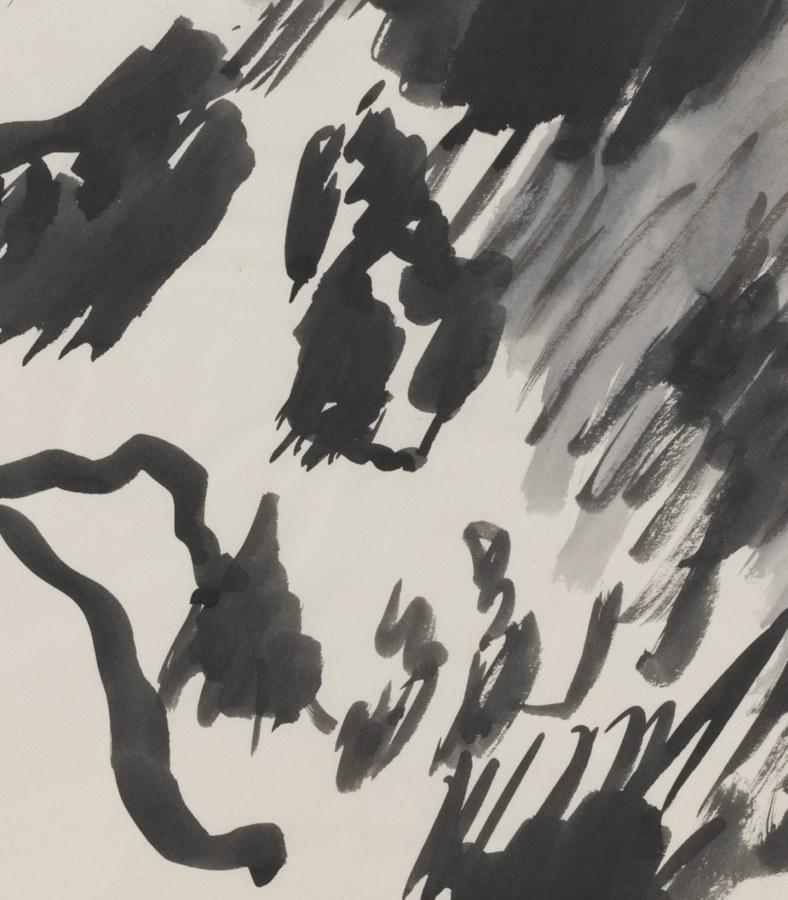

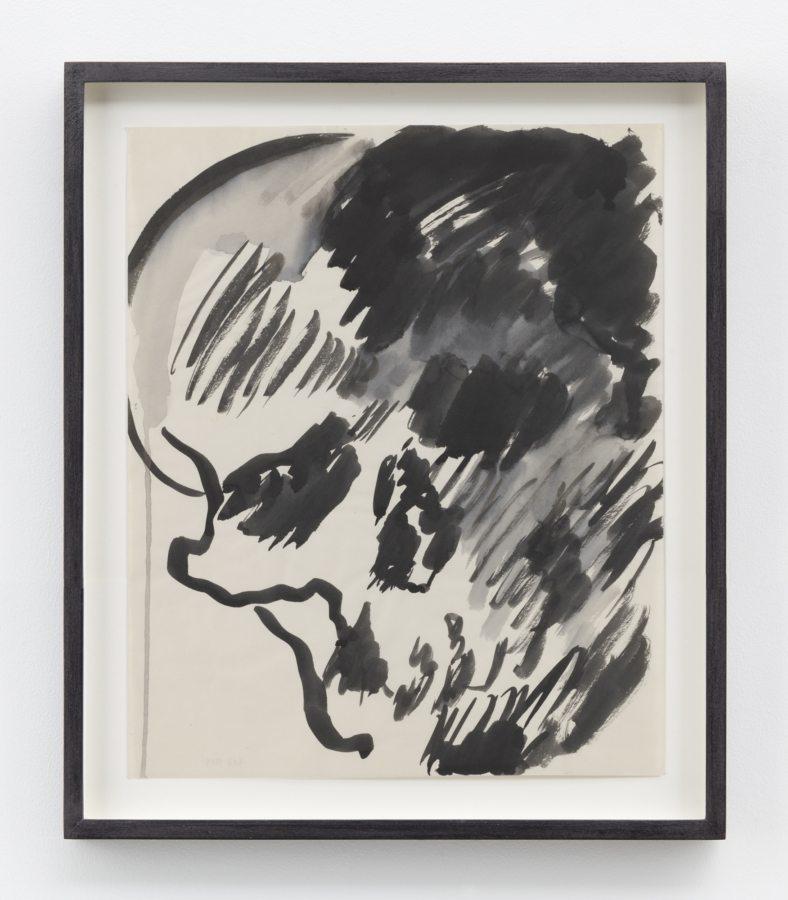

Even in Lee Lozano’s early still lifes—painted in 1960 probably while she was still in Chicago—there is that same sense of nervous disquiet, menace, and unpredictability that also mark the works she produced during her initial years in New York. Here she is confronting the still-life tradition, but instead of the paintings being balanced meditations on death and impermanence, they occupy space and practically force themselves on us. In contrast to the artist’s anatomical studies from her days at the Art Institute, the expressive, driven brushstrokes, harsh palette, and impasto application of paint used to depict a …. The dark eye sockets suck in the viewer’s gaze. The other still life deals with the unpredictability and uncertainty of life.

-Iris Müller-Westermann, Lee Lozano, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 2010

Lee Lozano

No title, c. 1960

Ink and brush on paper

16 3⁄4 × 13 7⁄8 inches; 42.7 × 35.2 cm

20 × 17 inches; 50.8 × 43.18 cm (framed)

Courtesy the Estate of Lee Lozano

and Hauser & Wirth

LL-60-001

Lee Lozano

No title, c. 1960

Ink and brush on paper

16 3⁄4 × 13 7⁄8 inches; 42.7 × 35.2 cm

20 × 17 inches; 50.8 × 43.18 cm (framed)

Courtesy the Estate of Lee Lozano

and Hauser & Wirth

LL-60-001

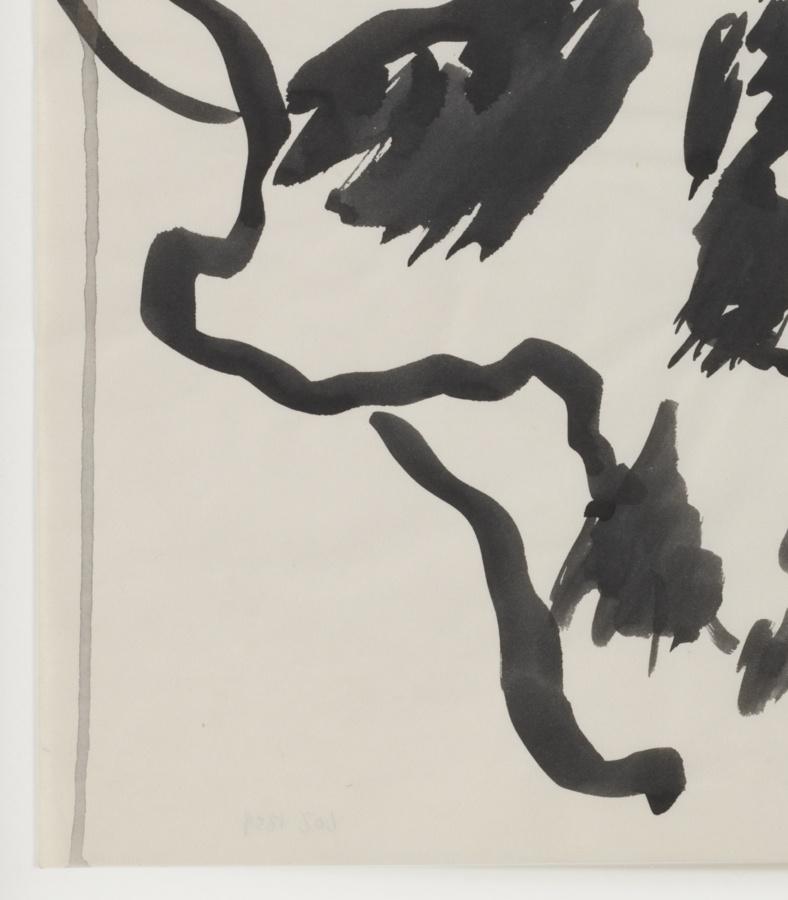

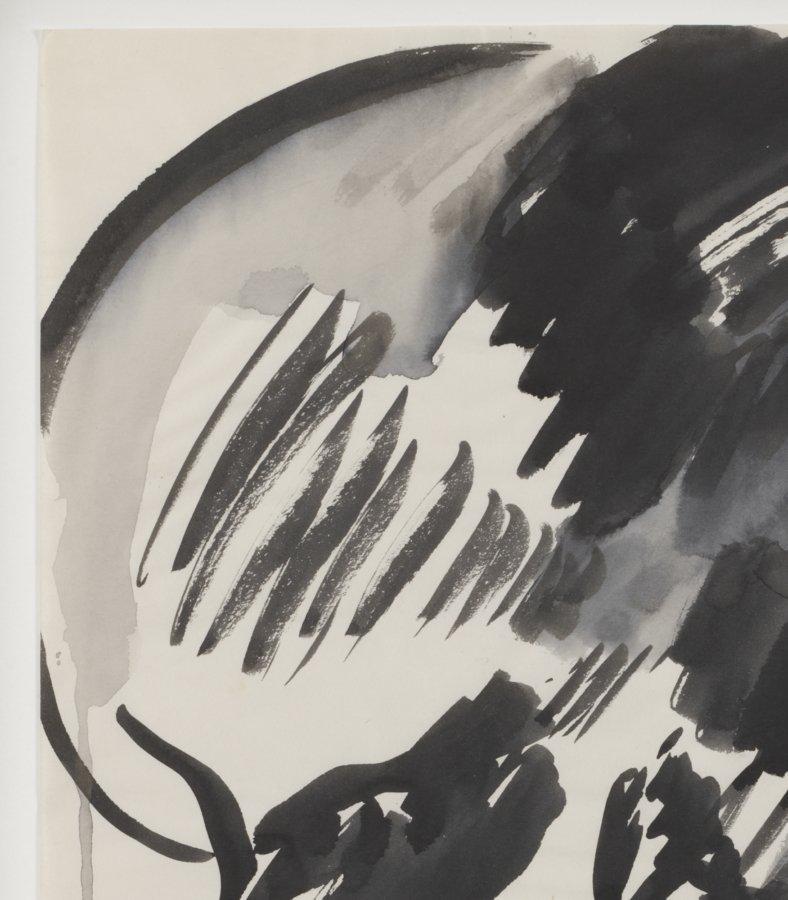

Lee Lozano

No title, c. 1960

Ink and brush on paper

16 3⁄4 × 13 7⁄8 inches; 42.5 × 35.2 cm

20 × 17 inches; 50.8 × 43.18 cm (framed)

Courtesy the Estate of Lee Lozano

and Hauser & Wirth

LL-60-002

Lee Lozano

No title, c. 1960

Ink and brush on paper

16 3⁄4 × 13 7⁄8 inches; 42.5 × 35.2 cm

20 × 17 inches; 50.8 × 43.18 cm (framed)

Courtesy the Estate of Lee Lozano

and Hauser & Wirth

LL-60-002

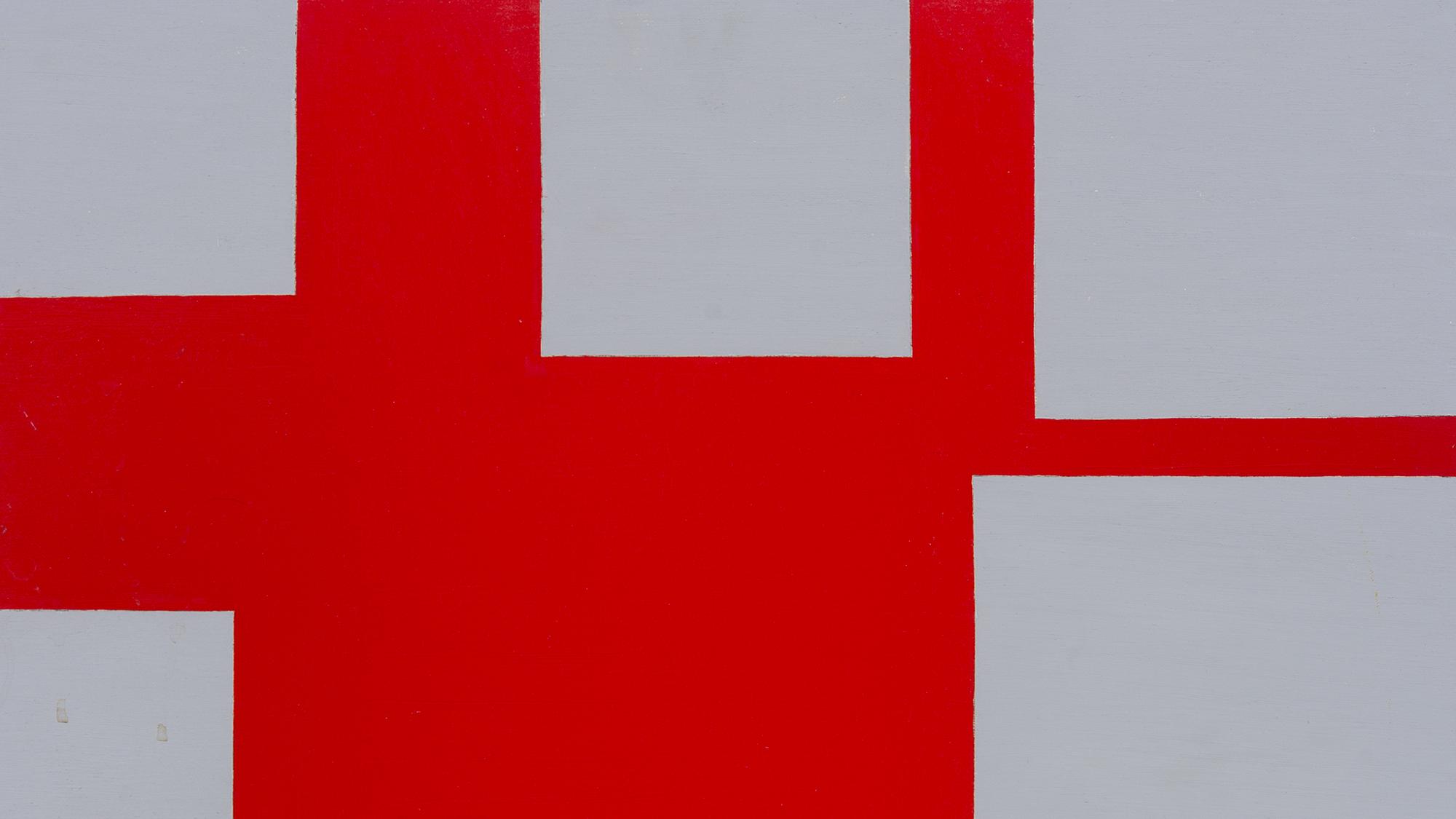

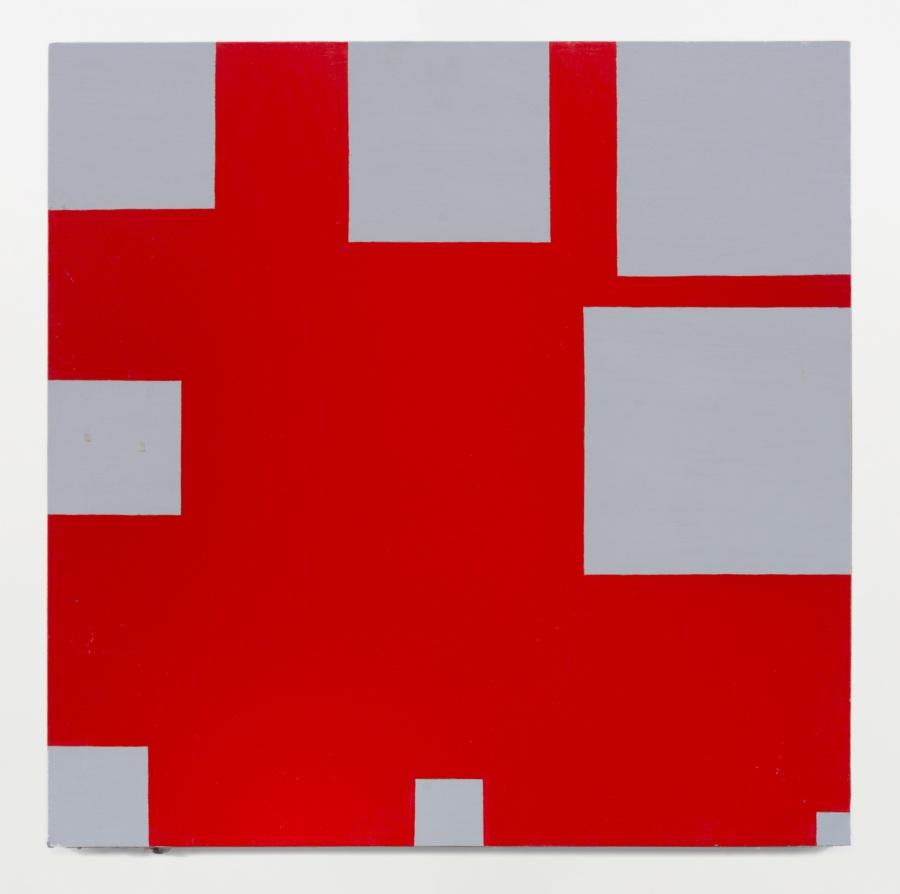

PAUL MOGENSEN

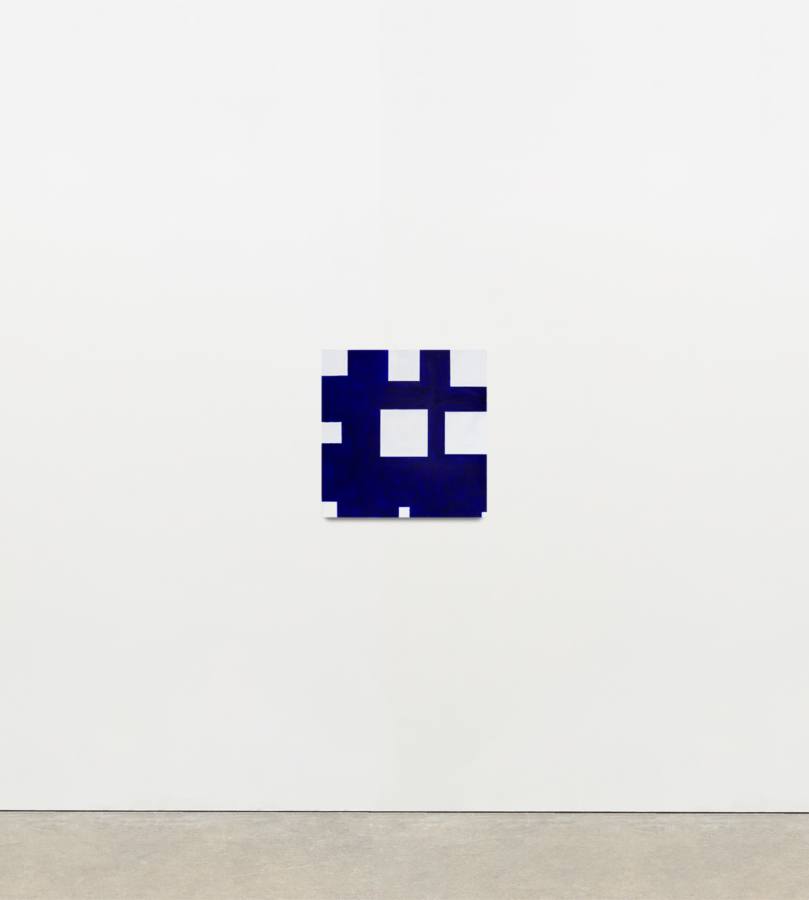

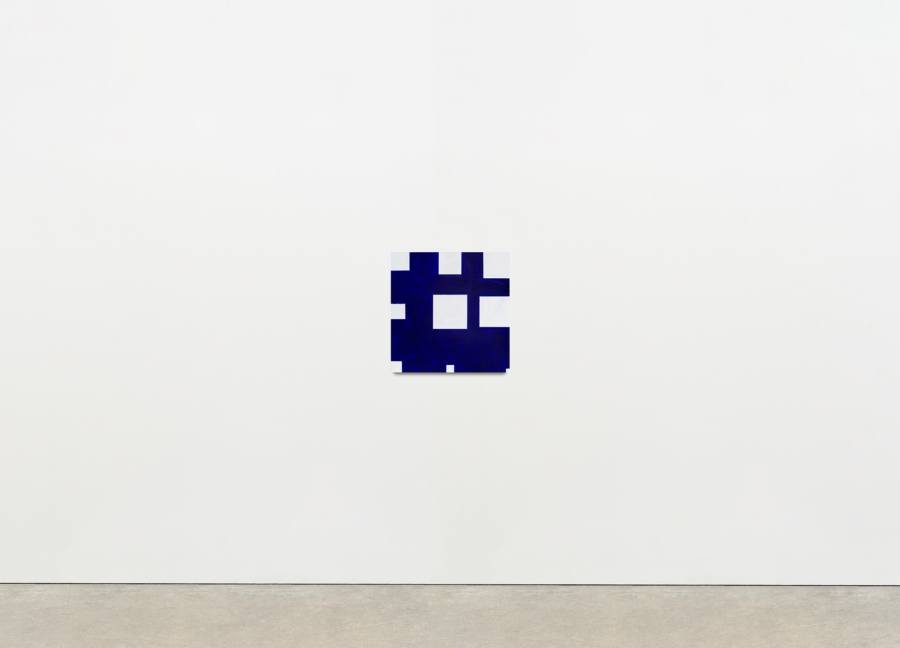

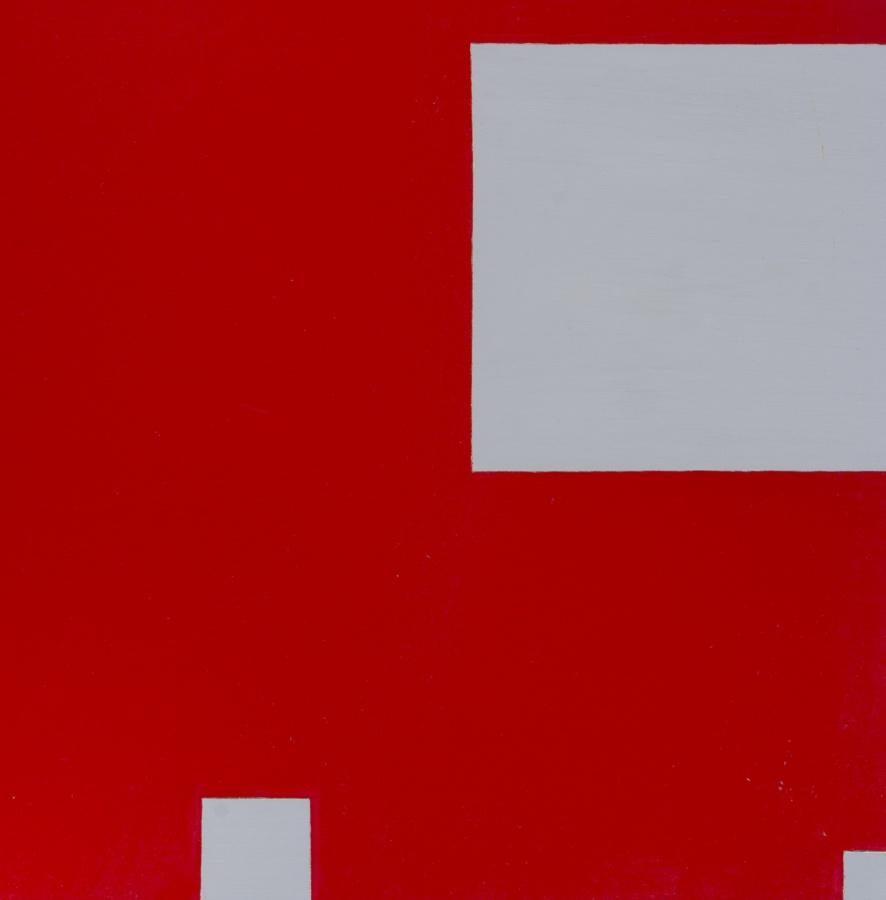

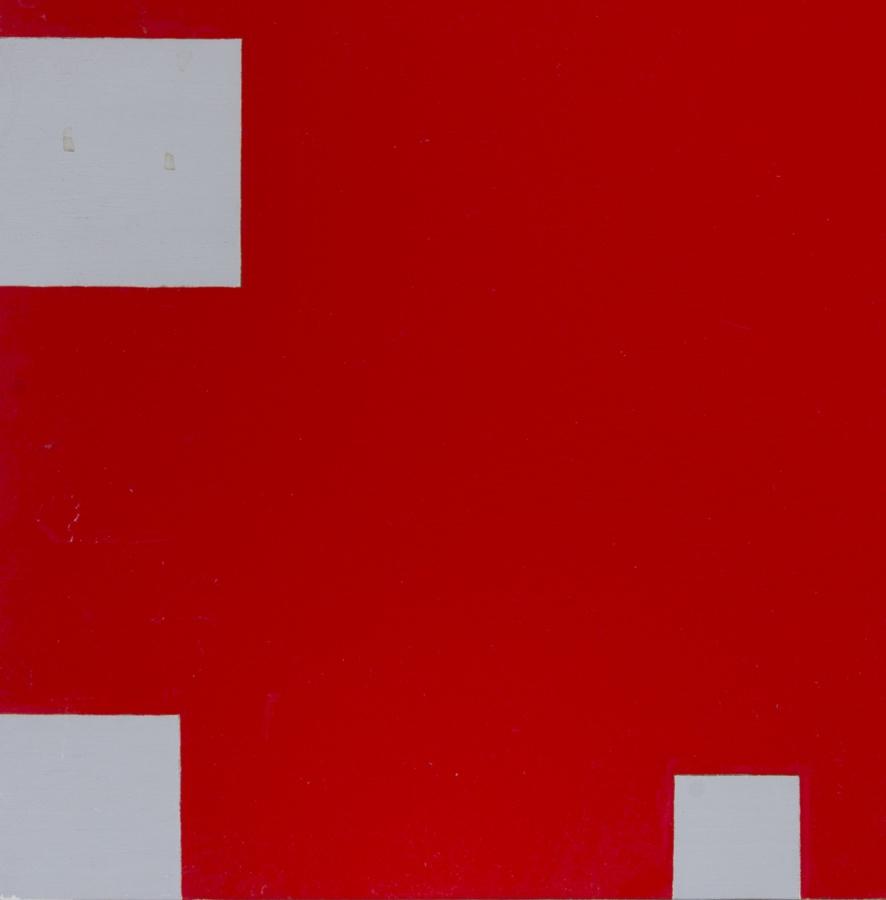

The steps that [Mogensen] took in his work toward reduction, his elimination of what he felt was unnecessary, set him on a trajectory that shares little with the reductive impulses we associate with Minimalism and geometric abstraction. The most obvious difference is that he neither employs a grid in his paintings nor makes monochrome paintings on a single plane. His primary interest is not in reiterating the plane, but in activating it…The initial realization that the painting is guided by a system leads to further curiosity. You begin trying to tease out the system or, if you cannot, you begin noticing the relationship between repetition and disruption. Kenneth Noland wanted to make paintings that you comprehend in an instant. Mogensen uses systems to explore different ways of seeing and looking….By getting viewers to engage with the painting’s structure — to see how it is put together — he invites us to recognize that the world is made of interconnected structures, not surfaces.

-John Yau, “The Spiraling Logic of Paul Mogensen,” Hyperallergic, 2018

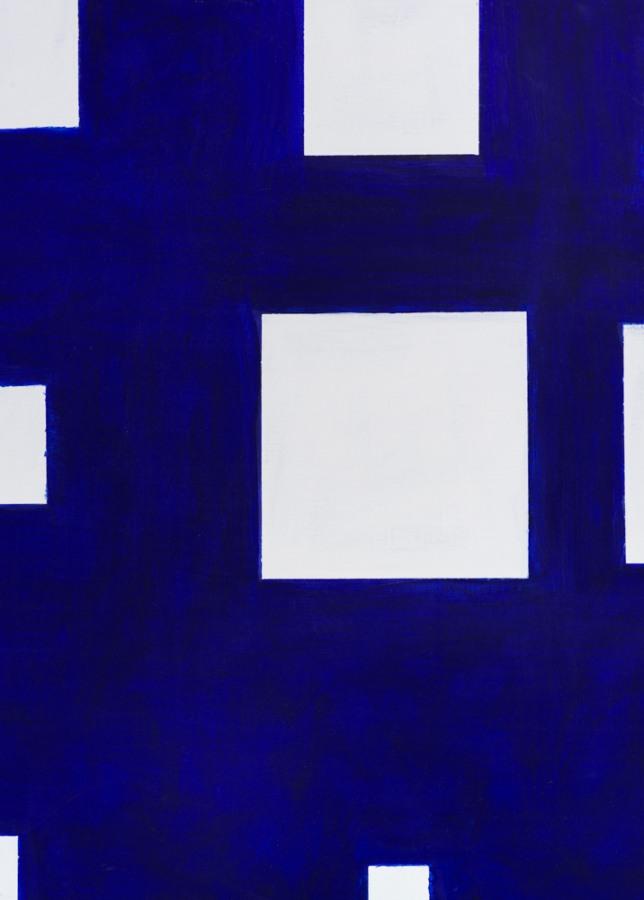

Paul Mogensen

no title (Thalo blue and white), 2016

Oil and stand oil on canvas

24 × 24 inches; 60.96 × 60.96 cm

PM-16-008

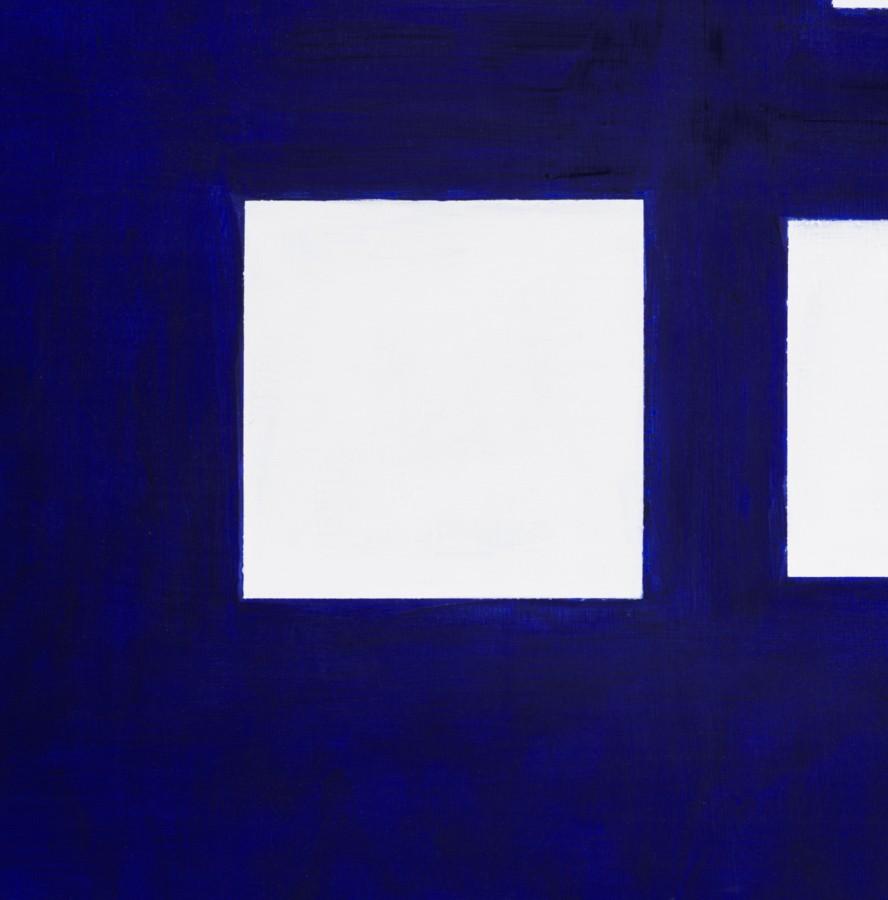

Paul Mogensen

no title (Thalo blue and white), 2016

Oil and stand oil on canvas

24 × 24 inches; 60.96 × 60.96 cm

PM-16-008

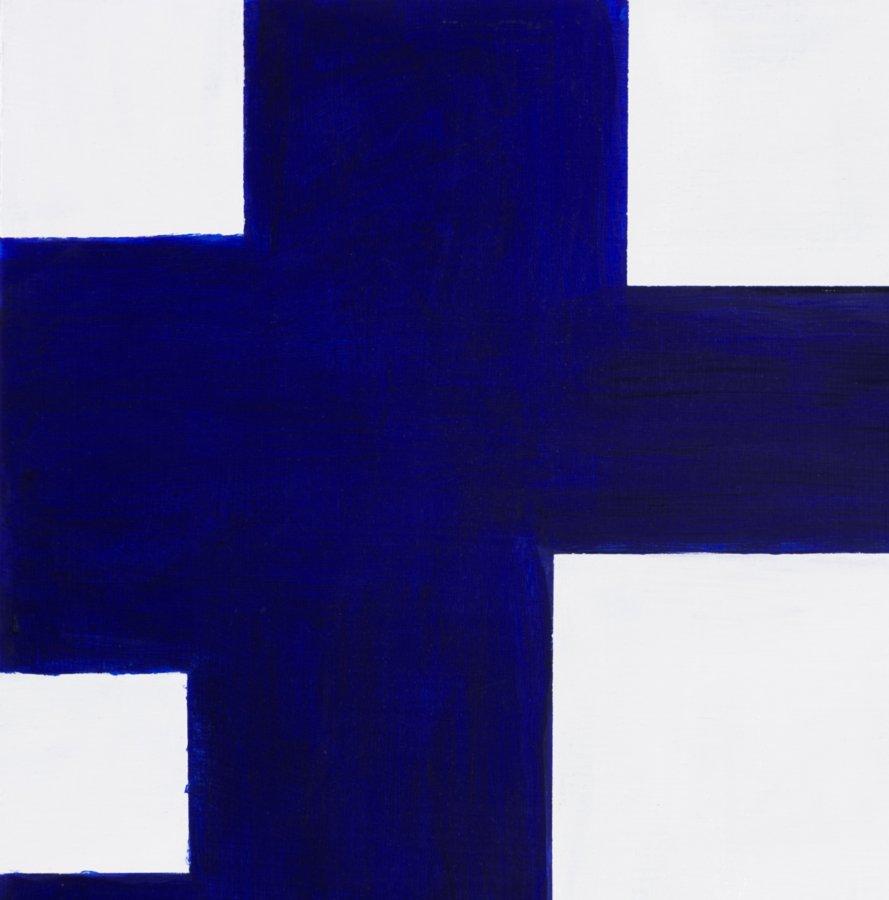

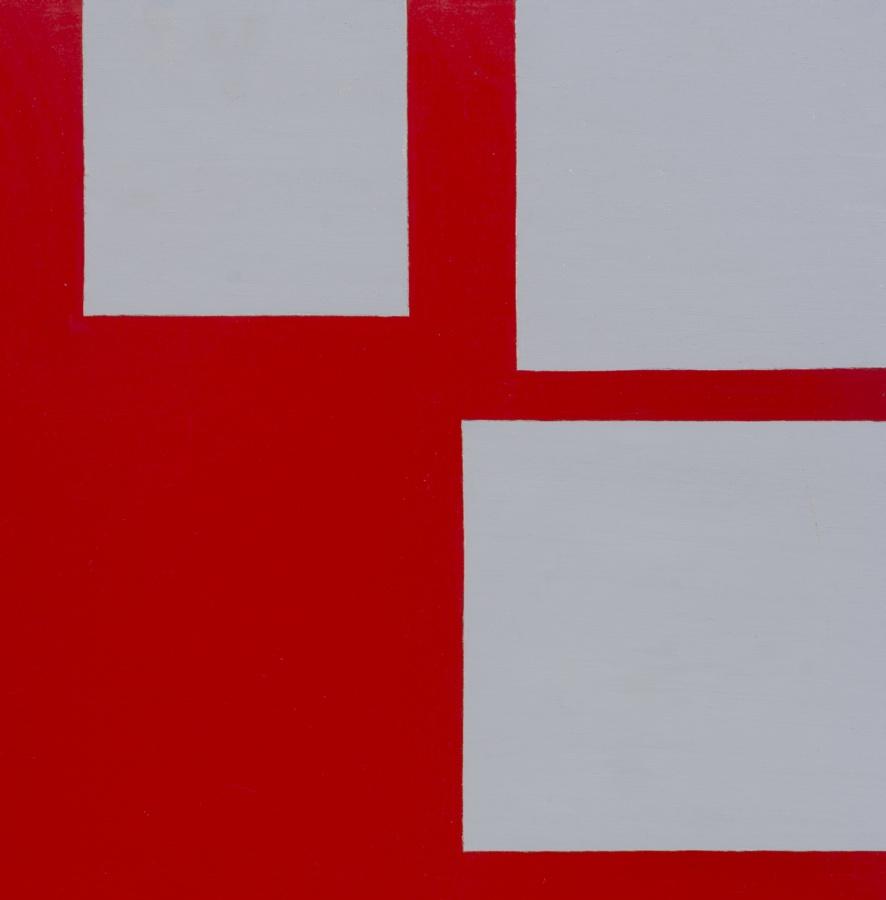

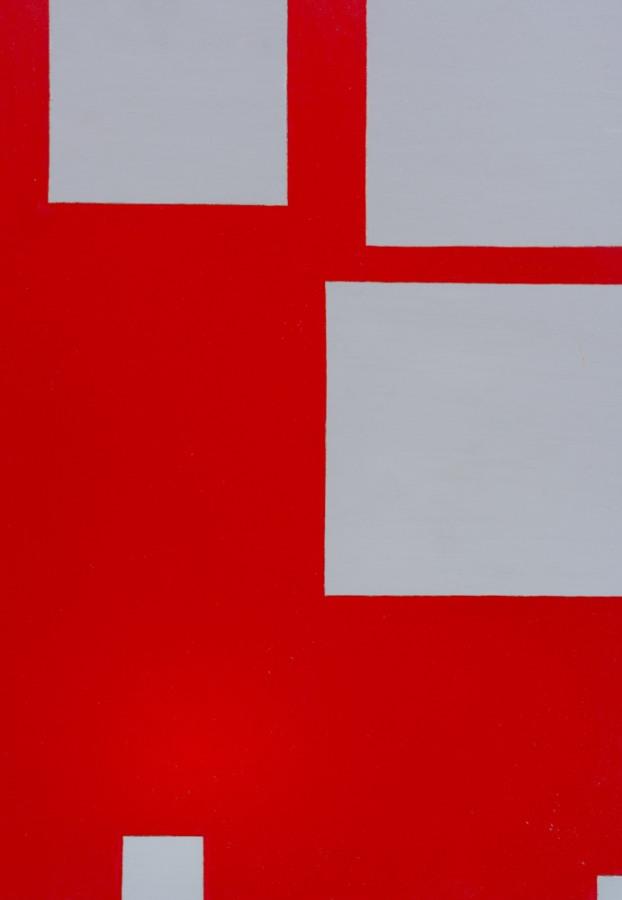

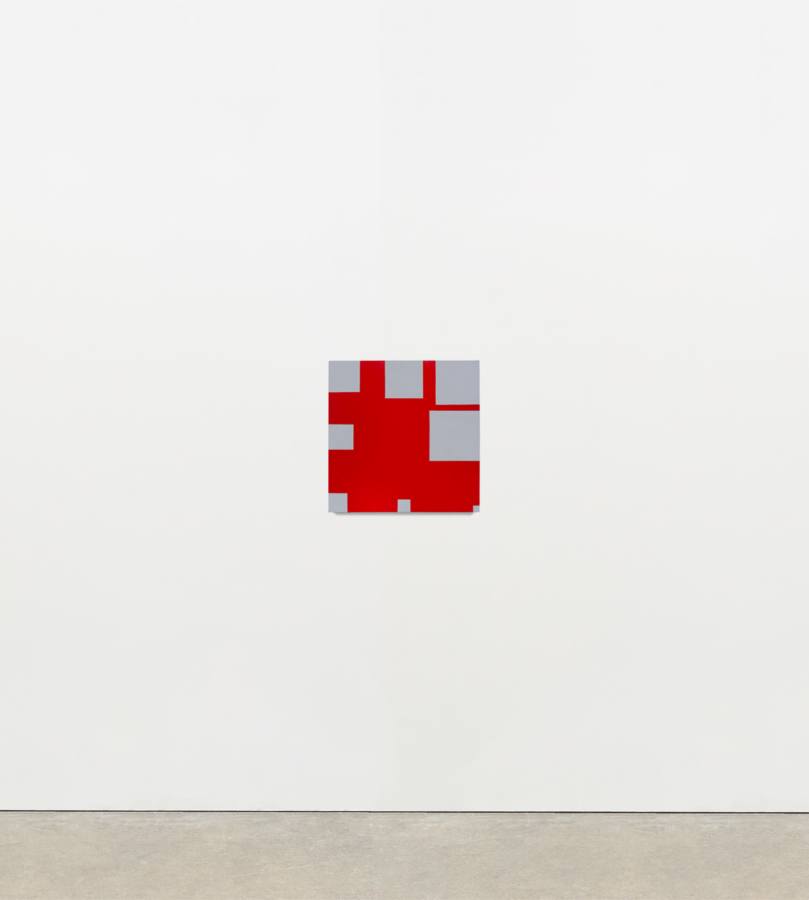

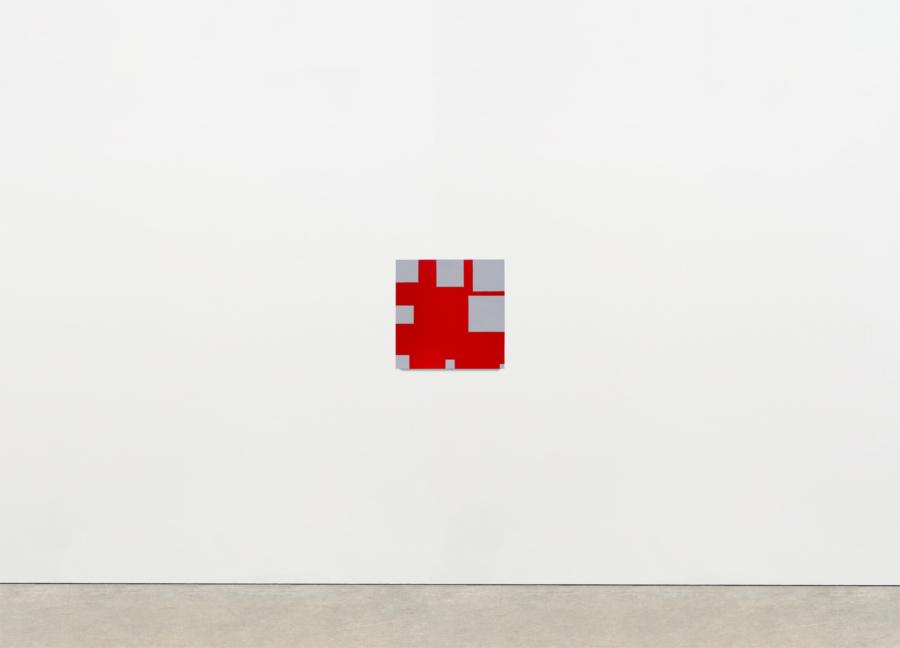

Paul Mogensen

no title (Portland Gray and Cadmium red Medium), 2016

Oil and stand oil on panel

24 × 24 inches; 60.96 × 60.96 cm

PM-16-001

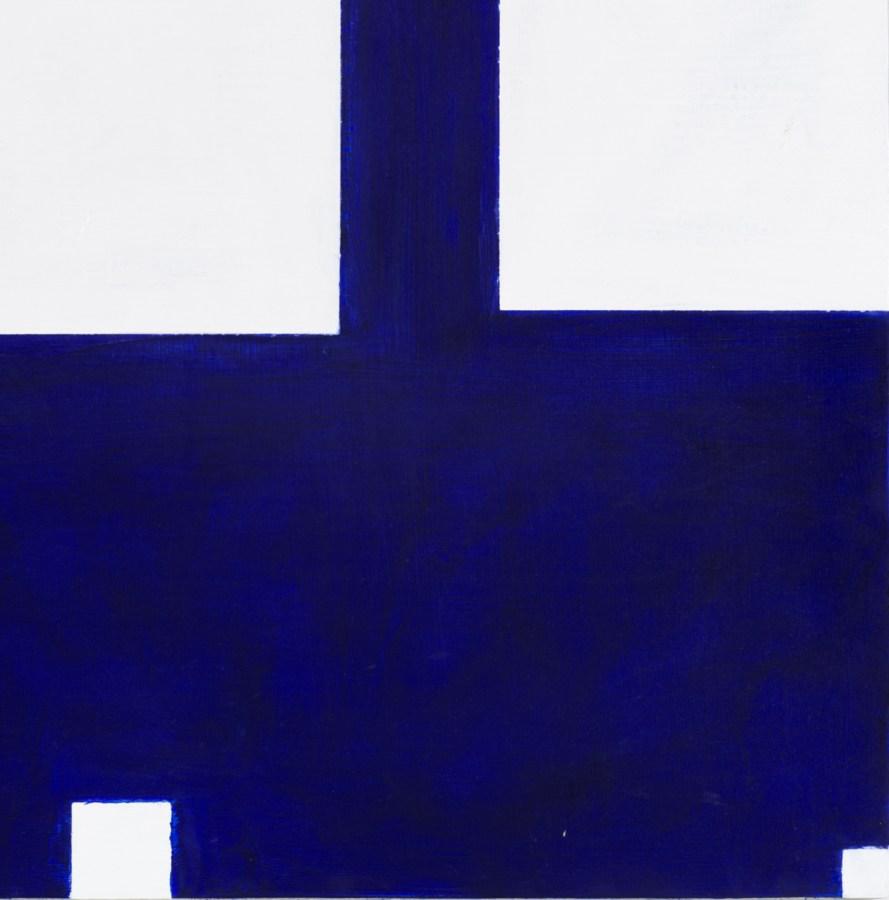

Paul Mogensen

no title (Portland Gray and Cadmium red Medium), 2016

Oil and stand oil on panel

24 × 24 inches; 60.96 × 60.96 cm

PM-16-001

Karma is pleased to participate in Frieze Sculpture New York with works by Thaddeus Mosley. A selection of Mosley’s works will be on view at Rockefeller Center from July–September 2020, curated by the Director of the Noguchi Museum, Brett Littman.

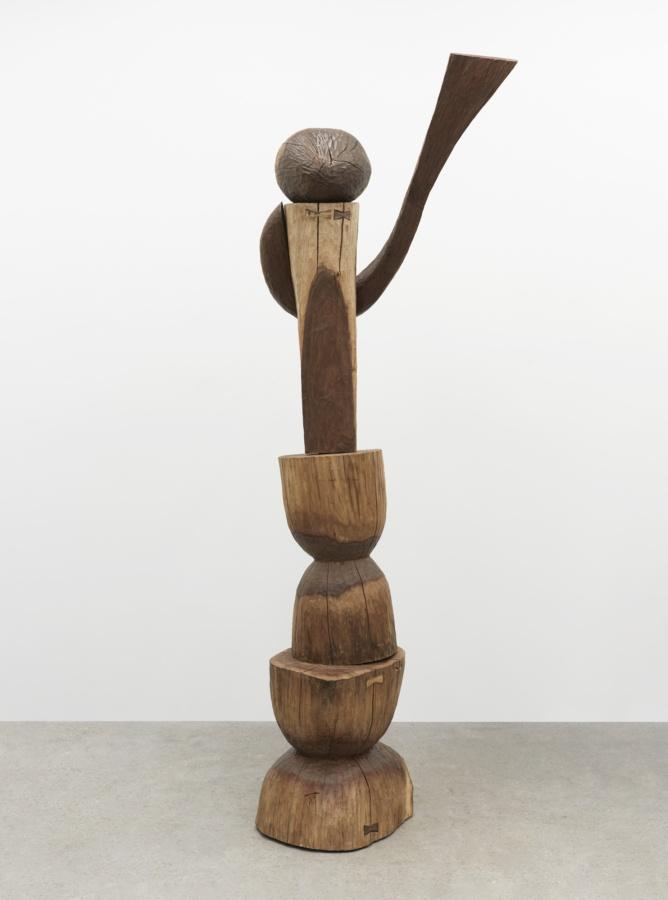

Painter Sam Gilliam describes Mosley as “a jazz critic, post-man, father, keeper of trees anywhere– / old trees, round trees, big trees, heavy trees.” Using only a mallet and chisel, Mosley’s monumental freestanding sculptures transform salvaged timber into new, biomorphic shapes that conjure an uncanny forest. The bold, sinuous curvature of these sculptures derive from existing recesses and protrusions in their raw material. Mosley uses traditional joinery techniques to manipulate form, weight, and space, as evidenced by gravity-defying sculptures like True to Myth (2019) and Intersect (2016).

Thaddeus Mosley Studio, Pittsburgh, PA. Photograph by Tom Little

Thaddeus Mosley Studio, Pittsburgh, PA. Photograph by Tom Little

Thaddeus Mosley home, Pittsburgh, PA. Photograph by Tom Little

Thaddeus Mosley home, Pittsburgh, PA. Photograph by Tom Little

Thaddeus Mosley

Intersect, 2016

Walnut

59 × 59 × 56 inches; 149.86 × 149.86 × 142.24 cm

TM-16-007

Thaddeus Mosley

Intersect, 2016

Walnut

59 × 59 × 56 inches; 149.86 × 149.86 × 142.24 cm

TM-16-007

Thaddeus Mosley

True to Myth, 2019

Walnut

100 × 36 inches; 254 × 91.44 cm

TM-19-004

Thaddeus Mosley

True to Myth, 2019

Walnut

100 × 36 inches; 254 × 91.44 cm

TM-19-004

Thaddeus Mosley

Illusory Progression, 2016

Walnut, ash

96 × 24 × 18 inches; 243.84 × 60.96 × 45.72 cm

TM-16-005

Thaddeus Mosley

Illusory Progression, 2016

Walnut, ash

96 × 24 × 18 inches; 243.84 × 60.96 × 45.72 cm

TM-16-005

Woody De Othello, 2020. Photograph by Aubrey Mayer

WOODY DE OTHELLO

Woody de Othello draws on the city’s artistic lineage as well as its political legacy to create his surreal, anthropomorphic sculpture. A ceramicist first—although he paints, draws and works with found objects—his sculpture is loose and large, often slumped precariously and fired in a multitude of colors reminiscent of Ron Nagle, though adapting none of Nagle’s sleek compact forms. “It’s a question of ‘how can I afflict the sculptures with a human quality or an emotive quality?’” he says, citing Ruby Neri and others from the Mission School as inspiration.

-Woody De Othello in conversation with Elizabeth Karp-Evans, “30 Under 35 2020: Woody De Othello Mixes Playful with Political,” Cultured Magazine, 2019

Woody De Othello

Speak Up, 2020

Ceramics, underglaze and glaze

44 × 16 × 16 inches; 111.8 × 40.6 × 40.6 cm

WDO-20-007

Woody De Othello

Speak Up, 2020

Ceramics, underglaze and glaze

44 × 16 × 16 inches; 111.8 × 40.6 × 40.6 cm

WDO-20-007

Woody De Othello

In a Blue Mood, 2019

Acrylic, gouache, and watercolor

18 × 24 inches; 45.72 × 60.96 cm

WDO-19-028

Woody De Othello

In a Blue Mood, 2019

Acrylic, gouache, and watercolor

18 × 24 inches; 45.72 × 60.96 cm

WDO-19-028

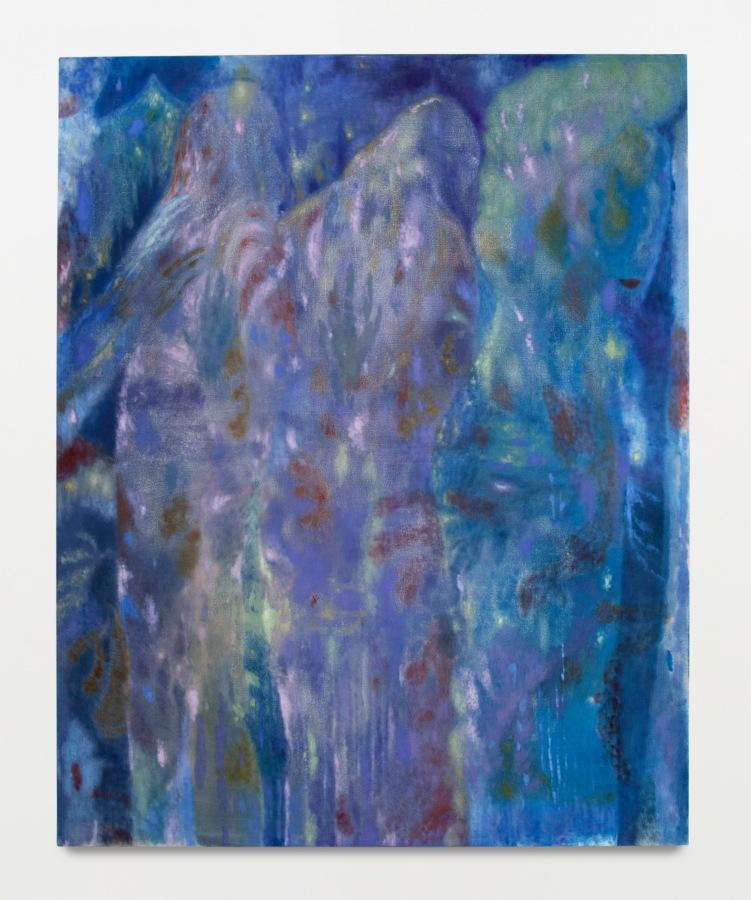

MAJA RUZNIC

“Mythology allows me to speak about human suffering in a softer way than if the work was more literal. Surviving a war has taught me that sharpness, emotional as well as physical, creates division and perpetuates violence. So I take this idea of softness and apply it to the actual process of painting — scumbling, blurring and allowing shapes to bleed into one another. Symbolically, I’m trying to destabilize borders. I see myths and stories as having more welcoming shapes — soft and round like stuffed animals. I feel called to communicate not to the brains of people but to their bones and hearts. I hope my work activates something nostalgic, familiar and even sad. Myths are full of darkness and suffering but beauty in how they’re told.”

-Maja Ruznic, in conversation with Christina Nafziger, “Myths Full of Darkness and Suffering Beautifyly Told By Maja Ruznic,” Art Maze Magazine, 2018

Maja Ruznic Studio, Roswell, New Mexico

Maja Ruznic Studio, Roswell, New Mexico

Maja Ruznic

The Called, 2020

Acrylic and oil on canvas

67 1⁄2 × 53 1⁄2 inches; 171.5 × 136 cm

MR-20-001

Maja Ruznic

The Called, 2020

Acrylic and oil on canvas

67 1⁄2 × 53 1⁄2 inches; 171.5 × 136 cm

MR-20-001

Kathleen Ryan Studio, Jersey City, New Jersey

Kathleen Ryan Studio, Jersey City, New Jersey

Kathleen Ryan Studio, Jersey City, New Jersey

Kathleen Ryan Studio, Jersey City, New Jersey

Installation view of Kathleen Ryan, Bad Fruit, Francois Ghebaly Gallery, Los Angeles, 2020

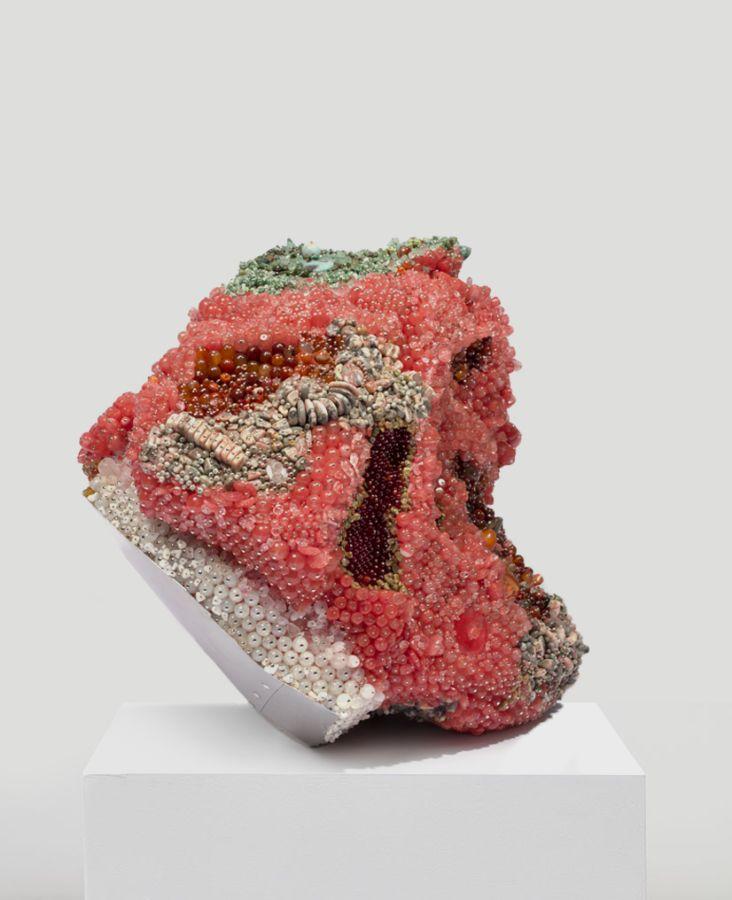

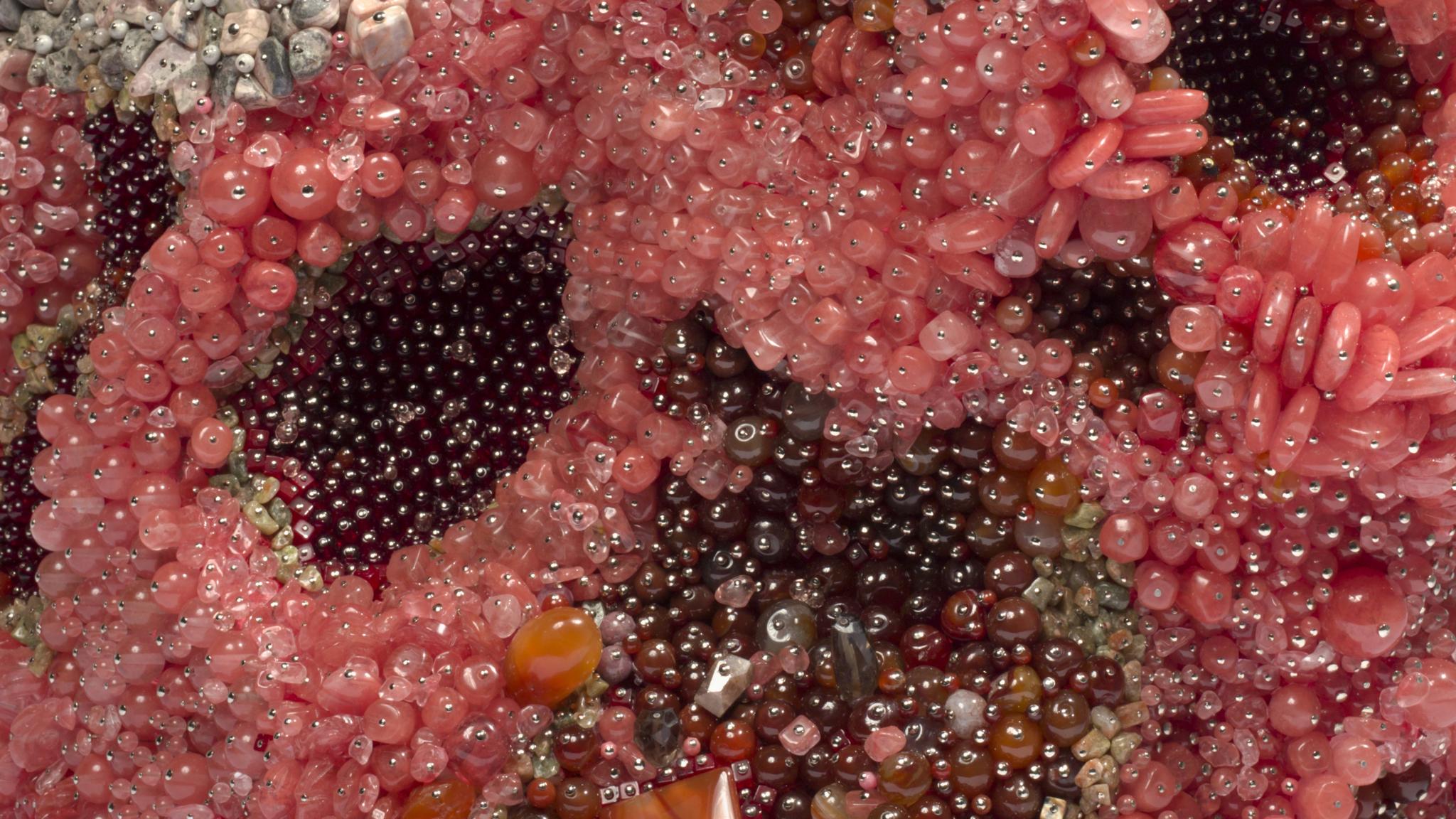

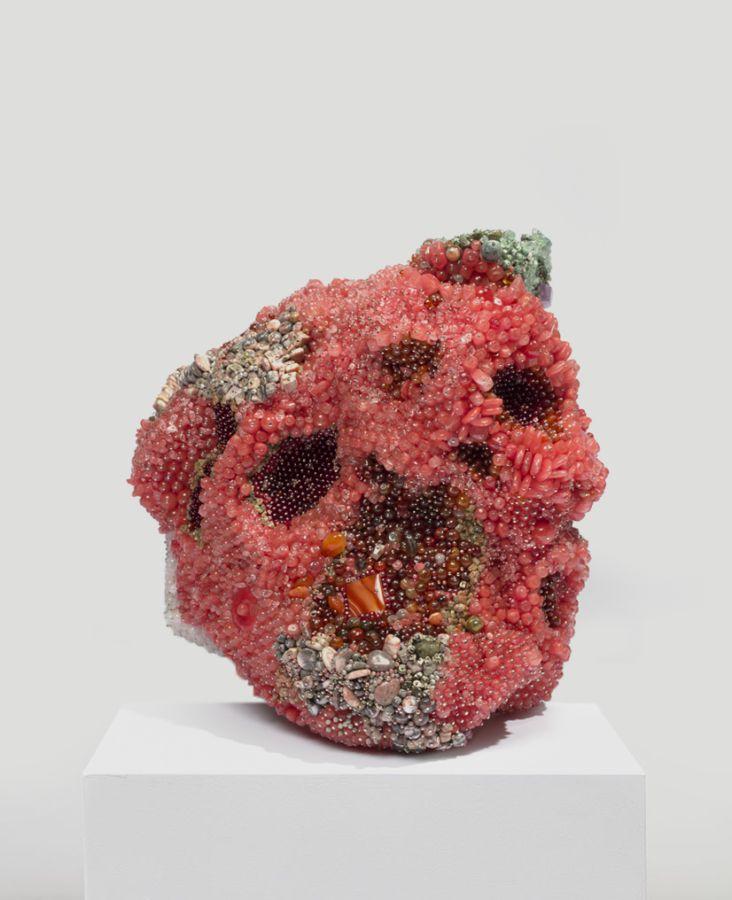

KATHLEEN RYAN

“While each gem is itself hard and lustrous, together they simulate colonies of fuzzy mold, particularly the common fungus known as green rot (Penicillium digitatum). The sculptures are beautiful and pleasurable, but there’s an ugliness and unease that comes with them,” Ryan says. Indeed, in their opulence and overripeness, the pieces recall the partially consumed fruit of 17th-century Dutch vanitas paintings by artists such as Jan Davidsz de Heem and Willem Claesz Heda, and likewise comment on worldly excess… “They’re not just opulent, there’s an inherent sense of decline built into them,” she says, “which is also something that’s happening in the world: The economy is inflating, but so is wealth inequality, all at the expense of the environment.” Tellingly, while she uses manufactured glass beads to create patches of ripe skin, the more expensive, naturally occurring gemstones are reserved for the rot. “Though the mold is the decay,” she says, “it’s the most alive part.”

-Alice Newell-Hanson, “The Sculptor Making Massive, Moldy Fruits From Gemstones,” T: The New York Times Magazine, 2019

Kathleen Ryan

Bad Melon (Chunk), 2020

Cherry quartz, rose quartz, agate, jasper, turquoise, fluorite, labradorite, pyrite, amazonite, amythest, aventurine, smoky quartz, rhodonite, rhodochrosite, rhyolite, magnesite, carnelian, citrine, calcite, glass, steel and stainless steel pins, polystyrene, and aluminum Airstream

15 1⁄2 × 18 × 17 1⁄2 inches; 39.37 × 45.72 × 44.45 cm

KR-20-001

Kathleen Ryan

Bad Melon (Chunk), 2020

Cherry quartz, rose quartz, agate, jasper, turquoise, fluorite, labradorite, pyrite, amazonite, amythest, aventurine, smoky quartz, rhodonite, rhodochrosite, rhyolite, magnesite, carnelian, citrine, calcite, glass, steel and stainless steel pins, polystyrene, and aluminum Airstream

15 1⁄2 × 18 × 17 1⁄2 inches; 39.37 × 45.72 × 44.45 cm

KR-20-001

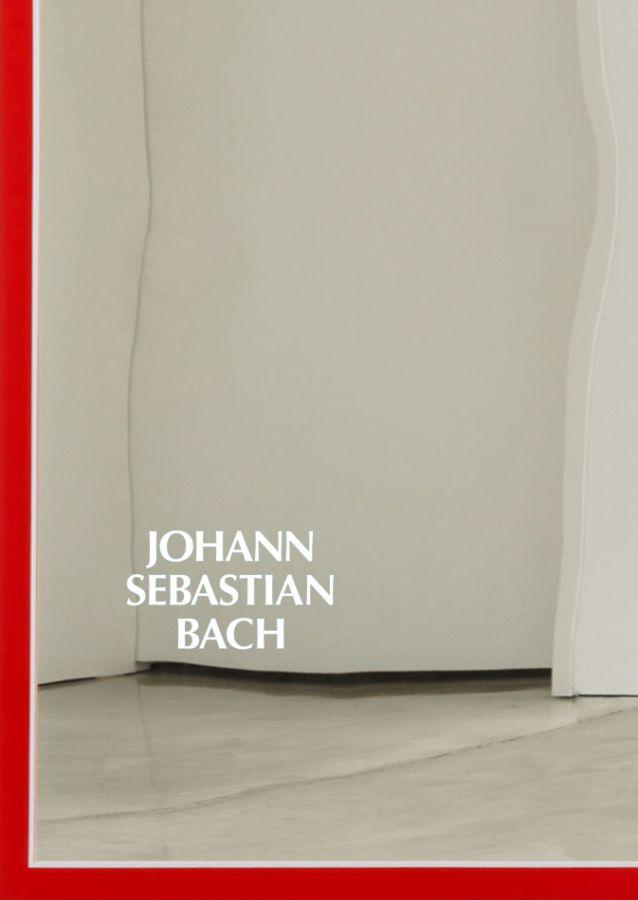

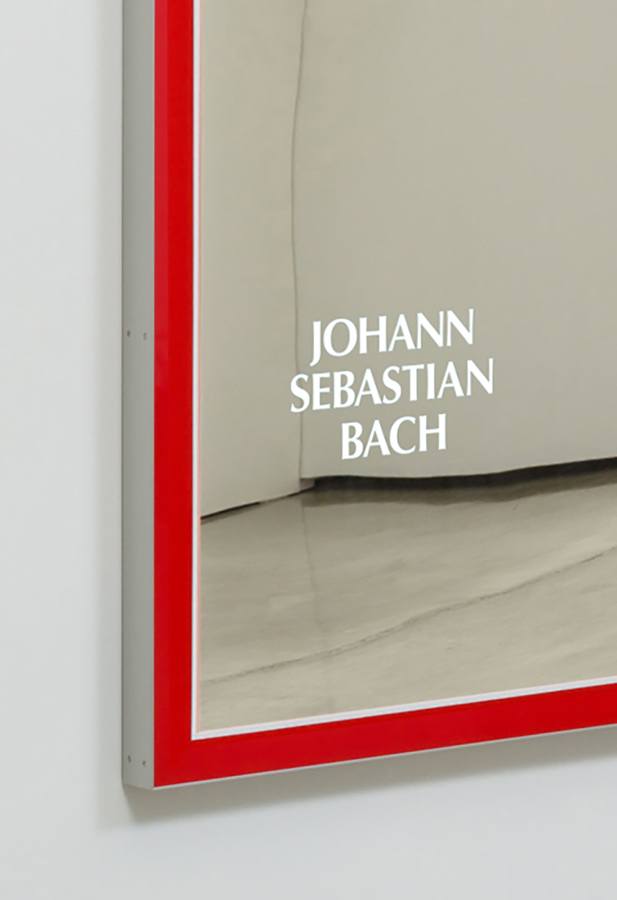

MUNGO THOMSON

My initial TIME piece was a series of around 90 drawings of the evolution of the TIME logo that were collected in a book that I produced with LACMA. The mirror series came after the book. They are unique, person-sized mirrors silkscreened with the border, logo, and other artifacts found on actual issues of TIME Magazine. This series came from the simple observation that time happens in a mirror. There was something intimate about that fact that I wanted to cultivate. I wanted someone to live with the artwork and see themselves reflected in it, every day, and that would complete the work.

-Mungo Thomson in conversation with Haley Mellin, “Taking Time with Mungo Thomson,” Garage, 2019

Mungo Thomson

December 27, 1968 (Johann Sebastian Bach), 2020

Enamel on low-iron mirror, poplar and aluminum

74 × 56 × 2 1⁄2 inches; 187.96 × 142.24 × 6.35 cm

MT-20-014

Mungo Thomson

December 27, 1968 (Johann Sebastian Bach), 2020

Enamel on low-iron mirror, poplar and aluminum

74 × 56 × 2 1⁄2 inches; 187.96 × 142.24 × 6.35 cm

MT-20-014

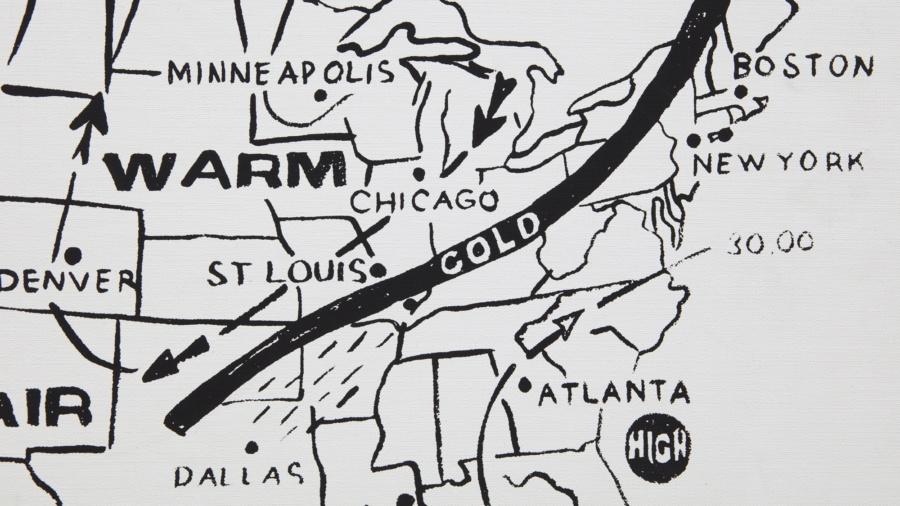

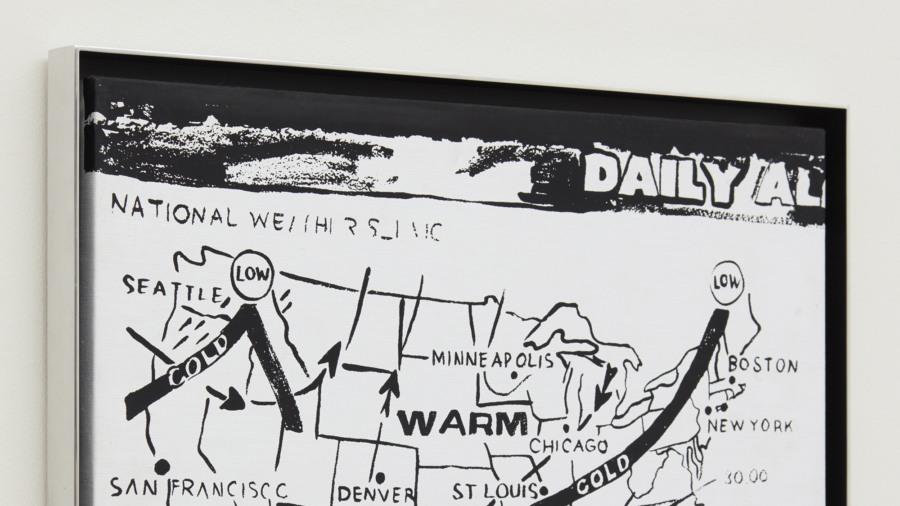

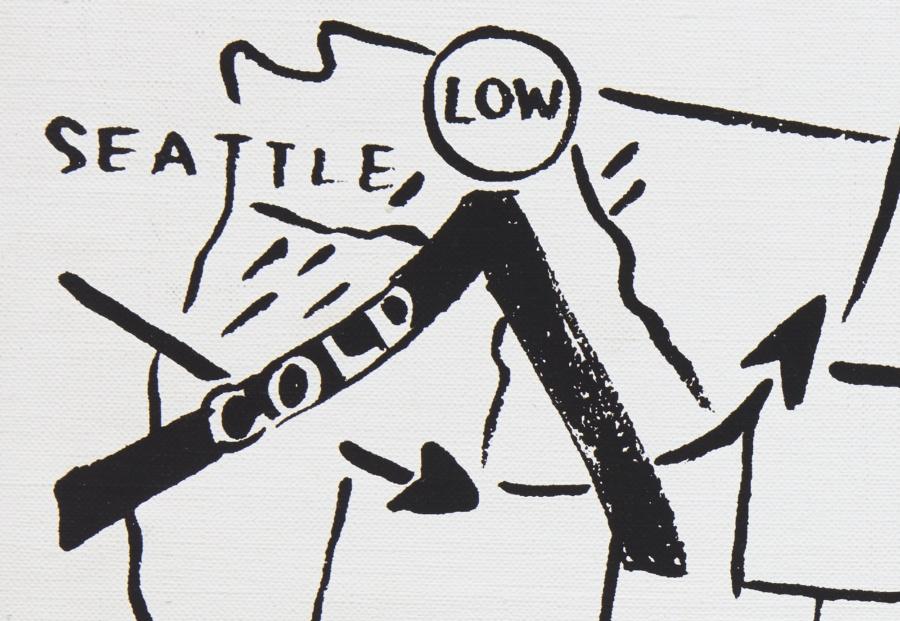

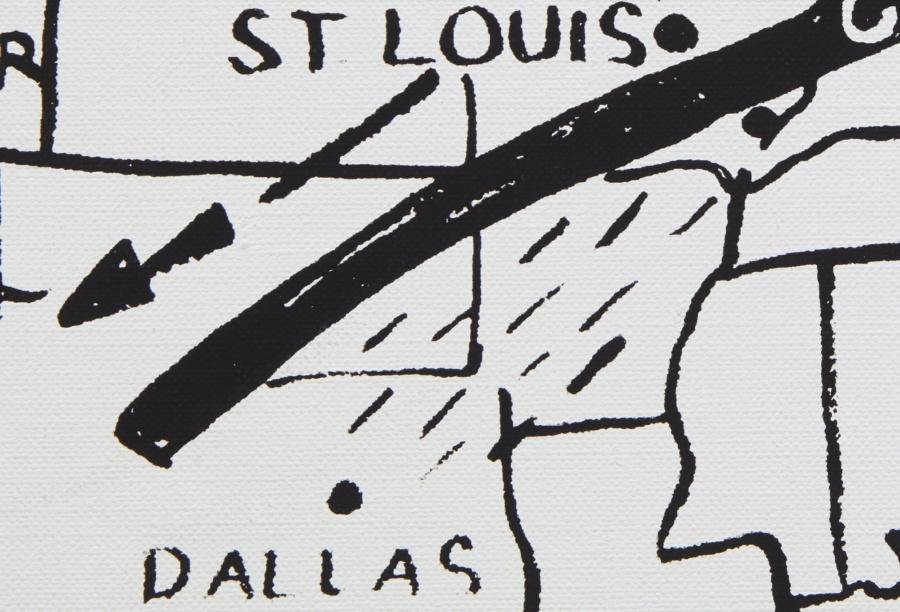

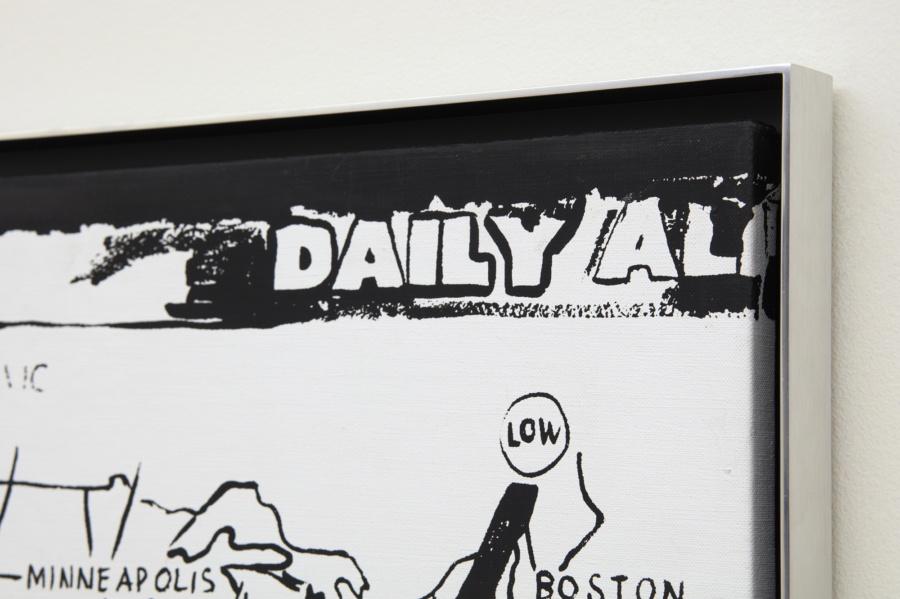

ANDY WARHOL

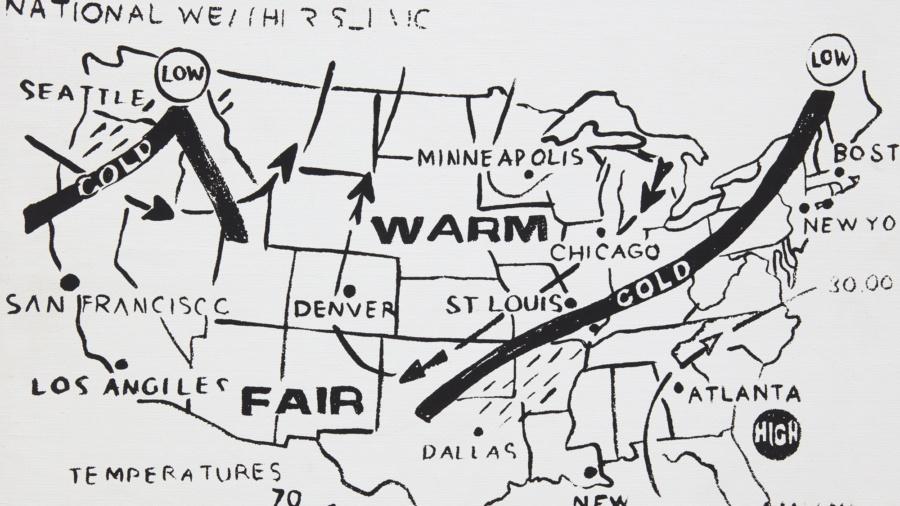

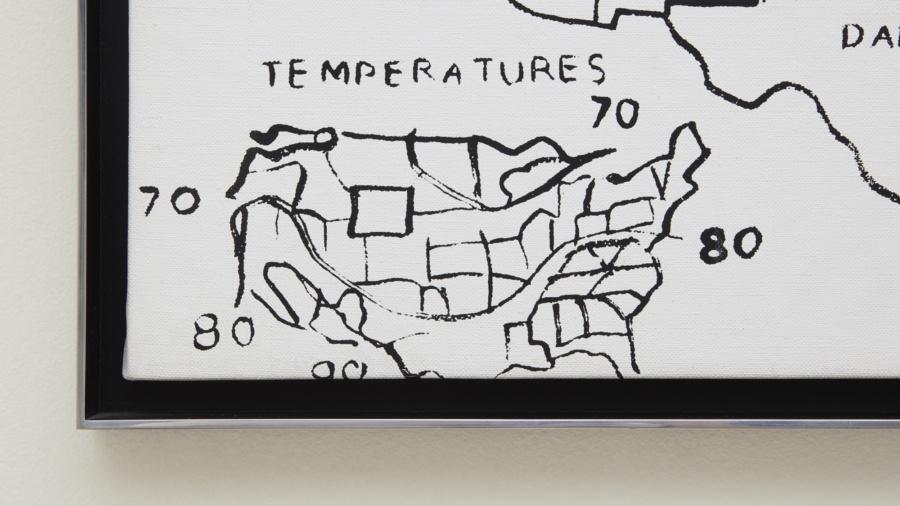

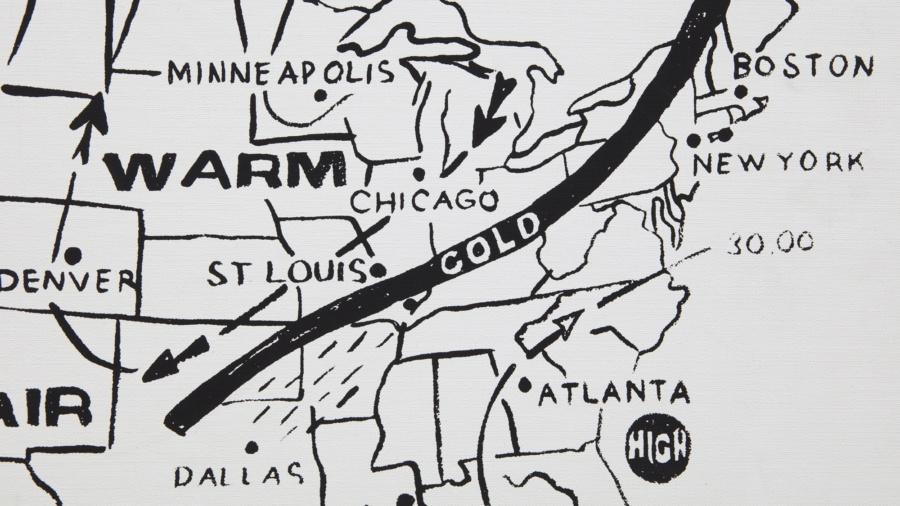

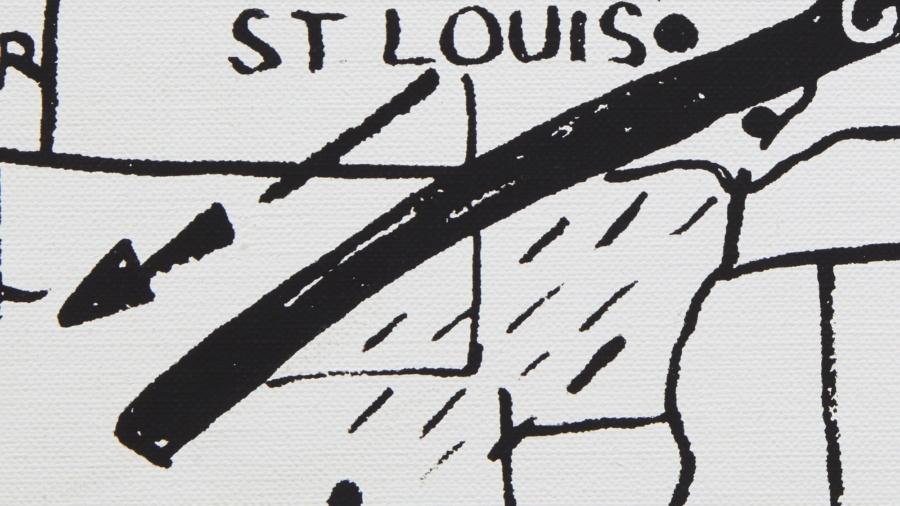

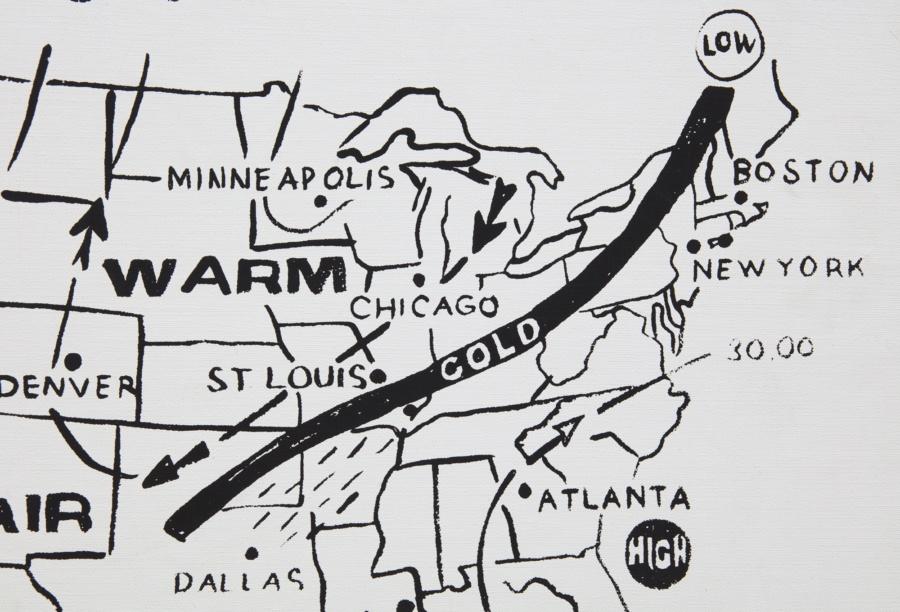

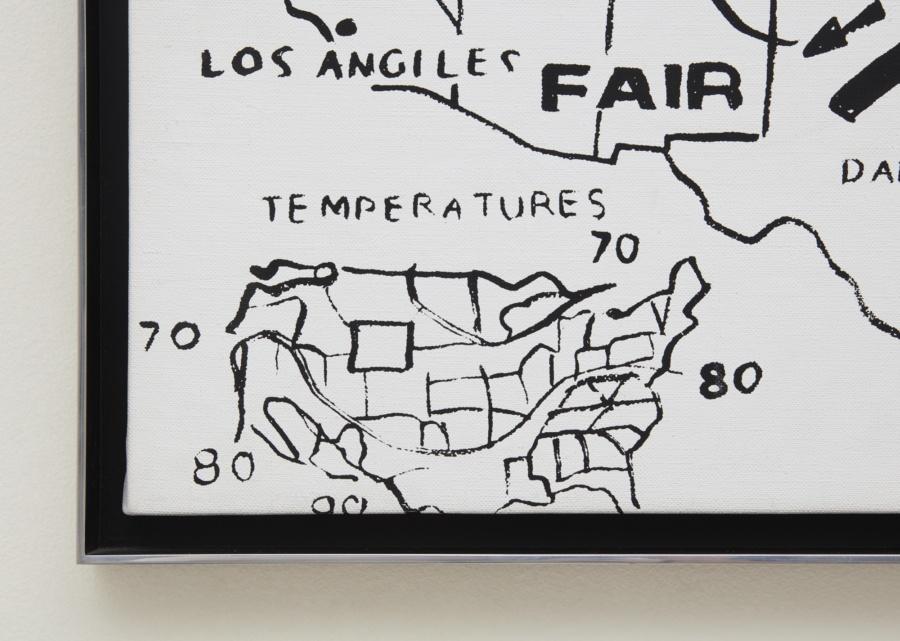

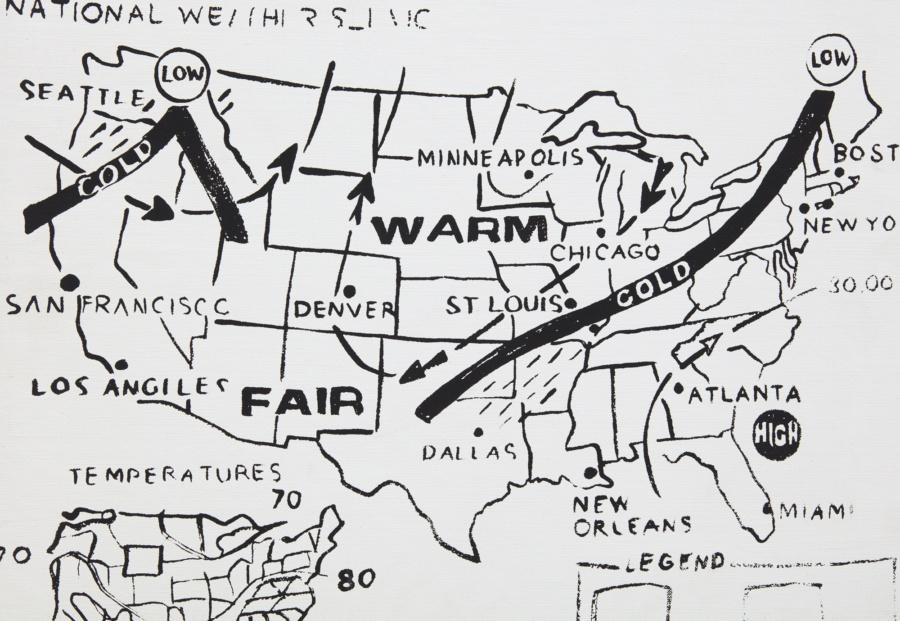

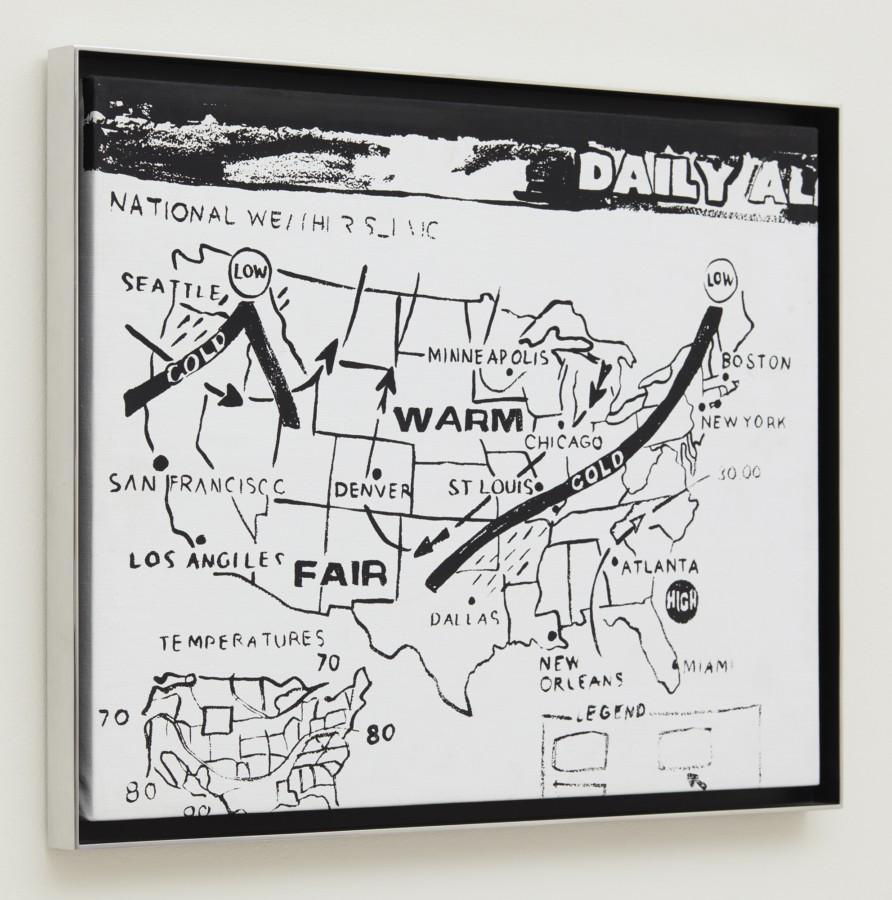

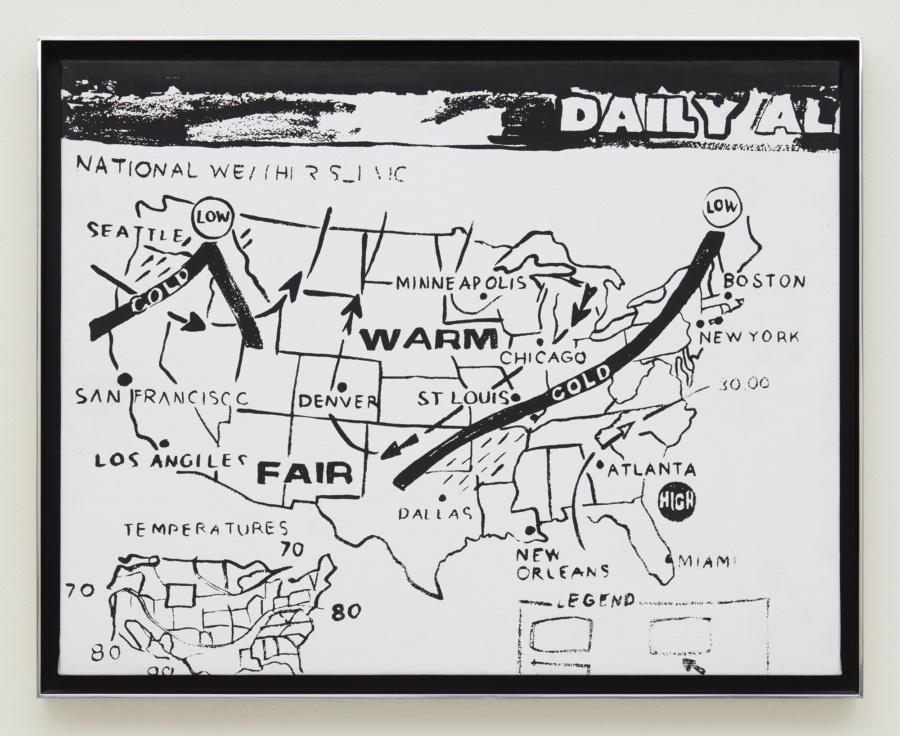

Andy Warhol

Weather Map (Positive), 1986

Synthetic polymer paint and silk screen ink on canvas

16 × 20 inches; 40.64 × 50.8 cm

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts

AW-86-001

Andy Warhol

Weather Map (Positive), 1986

Synthetic polymer paint and silk screen ink on canvas

16 × 20 inches; 40.64 × 50.8 cm

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts

AW-86-001

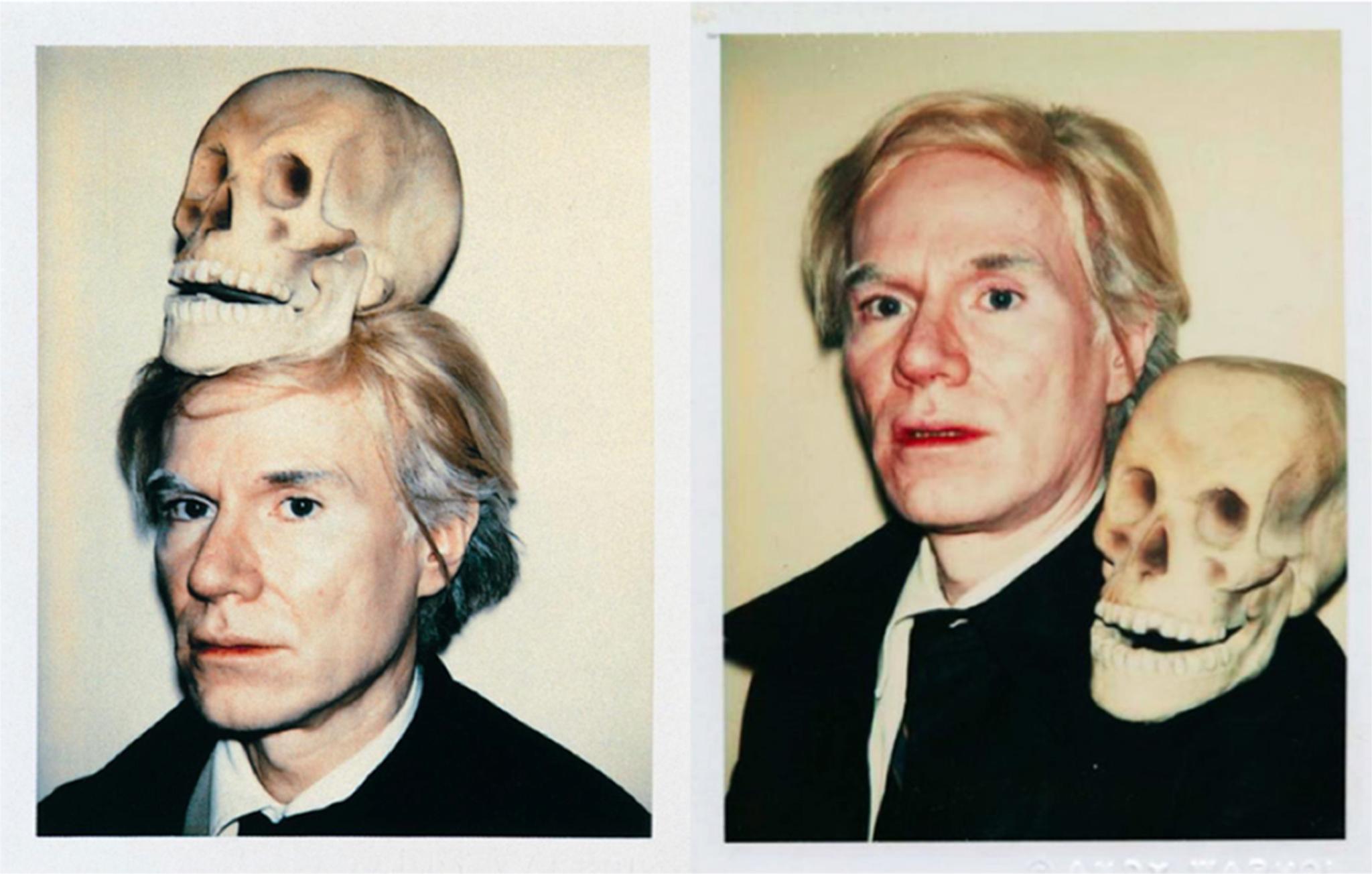

Andy Warhol (1928-1987), Self-Portrait with Skull, (1977) © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts

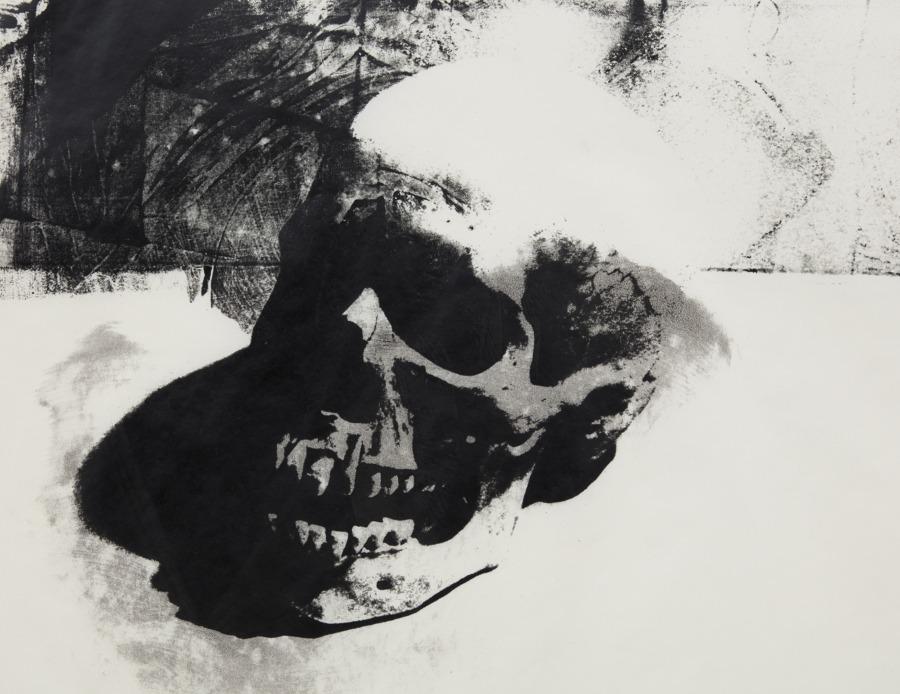

In October 1975, Andy Warhol’s series of drag queen portraits, Ladies and Gentlemen, went on display at Palazzo dei Diamanti, in Ferrara, northern Italy. Flying back from the opening, Warhol stopped in Paris and bought a human skull, either at a flea market or from a taxidermist shop according to differing accounts. Andy may have even bought the skull on Halloween […]

When he got back to New York, he had decided to work his Parisian find into his art. Handing it to an assistant to get it photographed, he said, “It’s like the classic still life; only there won’t be anything else, there will just be this big skull—and it’s everybody’s portrait in the world.”

[…]

Since his death in 1987, Warhol’s 1970s Skulls have been described as symbols for punk rock, nuclear war, the AIDS crisis and ecological disaster. Yet perhaps their true power lies in the way Warhol repeated his Skull image, again and again, until its deathly associations are replaced with a kind of empty ambiguity.

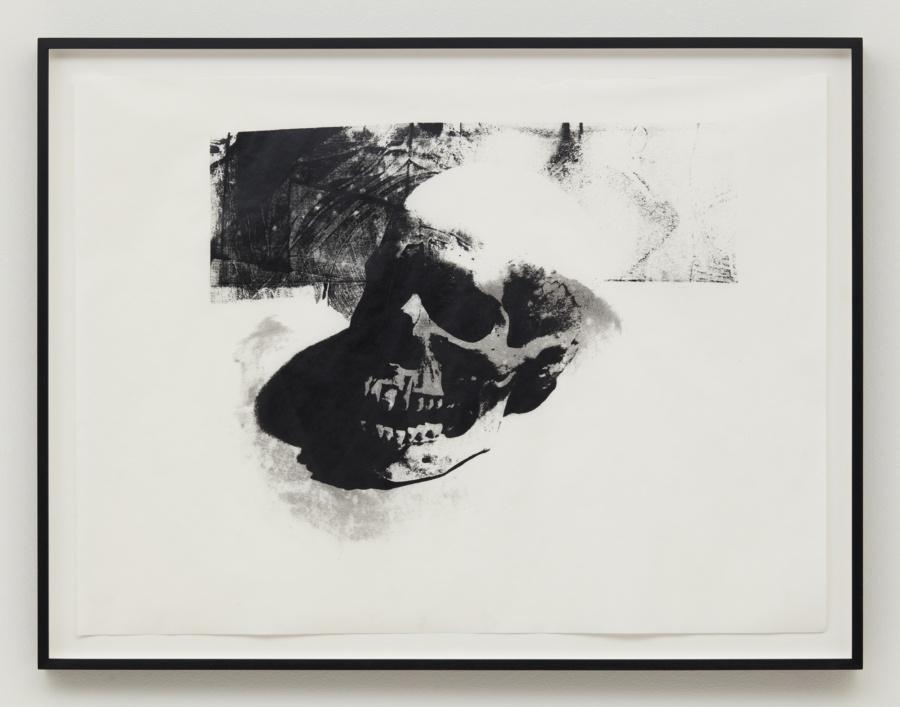

Andy Warhol

Skull, c. 1976

Screenprint on vellum

16 × 19 inches; 40.64 × 48.26 cm

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts

AW-76-001

Andy Warhol

Skull, c. 1976

Screenprint on vellum

16 × 19 inches; 40.64 × 48.26 cm

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts

AW-76-001