Lee Lozano

c. 1962

November 17–December 17, 2016

188 E 2nd Street

New York, NY 10009

Lee Lozano

c. 1962

November 17–December 17, 2016

188 E 2nd Street

New York, NY 10009

Karma is pleased to announce its inaugural exhibition at 188 East 2nd Street of early paintings by Lee Lozano, many of which have never been exhibited. The paintings, which are all small in scale, are concentrated with dense scenes of faces and figures fused with anthropomorphized objects almost bursting out of the confines of their frames.

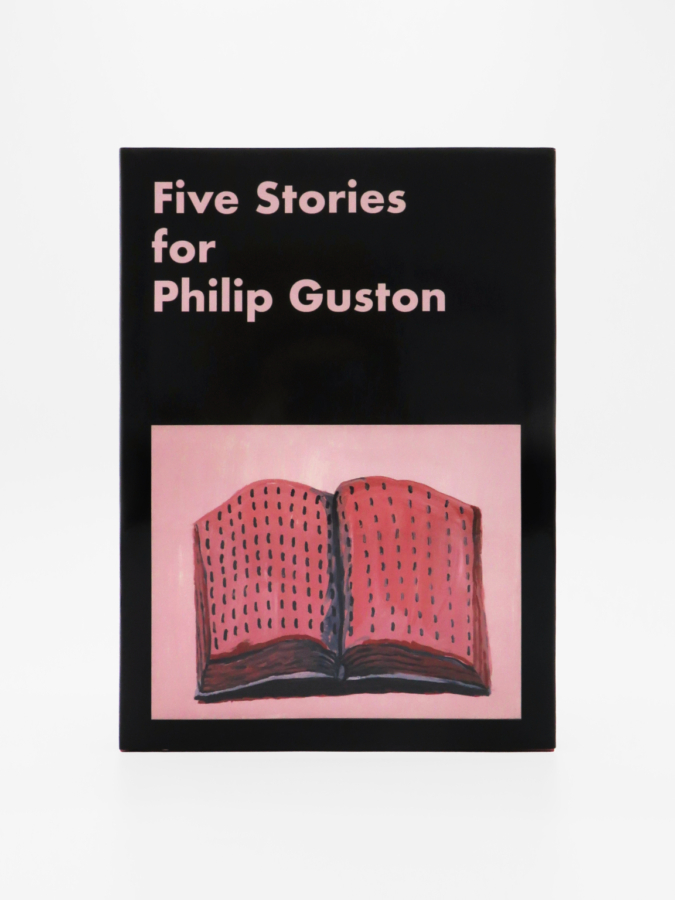

Lozano went to New York as a painter in the early 1960s. Her first major body of paintings was a rough-and-tumble mixture of cocks and cunts that morph together, mix ineluctably with, and transform into a variety of tools—screwdrivers, bolts, and hammers. The paint is thick, creamy, and sexy, and the overall images are arresting, as if the cartoon style of Philip Guston had somehow encountered contemporary cyborg fantasies of a complete merger of body and machine. The sexuality imaged in these paintings and drawings, all done in the early 1960s, is hardly the soft-core liberation offered by the then recently founded Playboy. It lends itself more to accounts of sexuality that stem from Freud’s theory of the polymorphous sexuality of children or Bataille’s Story of the Eye, which evokes a body that experiences a kind of perpetual slippage of meaning and signification—tits become balls, and balls become eyes, and eyes are like cunts, and so on. A polymorphously perverse account of sexuality lends itself to a feminist analysis, as it refuses to render the body and its sexuality hierarchical and implies instead a decentered experience of the body less dependent upon vision, voyeurism, spectacle, and objectification. Lozano’s evocation of this body is raucous, muscular, and simultaneously disturbing and deeply erotic (not that those two attributes are always different).

–excerpt from Tune In, Turn On, Drop Out: The Rejection of Lee Lozano by Helen Molesworth

These early works will be a surprise for those who came to Lozano through the Wave series and her conceptual / cerebral / performative propositions, and even the Tool paintings, which precede and to some extent inform them. The early ’60s paintings, while intimate in format, are densely packed with information. A few of these small paintings have a wide horizontal format, frieze-like despite their small scale. Within a few short years, Lozano would go on to create large, at times multi-part paintings that would appear to occupy or physically traverse the space of the room, but in the early ’60s she seems to have been working at a table or desk, in close proximity to her surface, giving an immediacy to the faster irreverent images, and a stillness to the spookier scenes. These works have been painted with a brushiness that has been built up, in some cases as if it was modeling paste, but then Lozano saw paint as “matter in solid state”—as opposed to Pollock, for whom she also identified it as matter, albeit in “liquid state,” and quite possibly even after it had dried. Her palette of chocolate and cocoa browns, ashen smudged blacks, steel grays, and dirty whites is offset by orange and red (how else to represent drops of blood and one possessed?) and on occasion, quite strikingly, a deep yet bright blue ground. The paintings are all framed, many with simple, thin strips of wood (from behind, the staples at each corner appear almost surgical, crudely so), a reminder that these works have now passed the half-century mark, the frame containing the image or tableau. In one painting, however, an elongated penis rises up from the bottom of the picture to penetrate a vertical form that occupies the right side, the tip of its head painted on the frame—its excitement or aggression defying the picture plane. In others, this “penis” emerges from the center of a face as an eroticized, exaggerated Pinocchio nose— man as pathological liar? Or simply boastful—extends from an eye and is poised between two fingers like a fat cigar, and is rendered serpentine, snakily invading a sculptural stage set. The appearance of a phallic form over an obliterated face resembles a baseball bat in one painting (with three crosses planted on top of the head, as if it was a graveyard, a Gothic “Boot Hill”) as a toothy blob bites its cheek, and a long, wide stake in another. Here, the solid bar-like object collides with a fiery, demonic face, a sharp pair of fangs identifying this creature as vampiric.

–excerpt from Paint First Don’t Last—Paint Last Don’t Care: Lee Lozano’s Early Work in the Early ’60s by Bob Nickas